Google is suing more than two dozen unnamed individuals allegedly involved in peddling a popular China-based mobile phishing service that helps scammers impersonate hundreds of trusted brands, blast out text message lures, and convert phished payment card data into mobile wallets from Apple and Google.

In a lawsuit filed in the Southern District of New York on November 12, Google sued to unmask and disrupt 25 “John Doe” defendants allegedly linked to the sale of Lighthouse, a sophisticated phishing kit that makes it simple for even novices to steal payment card data from mobile users. Google said Lighthouse has harmed more than a million victims across 120 countries.

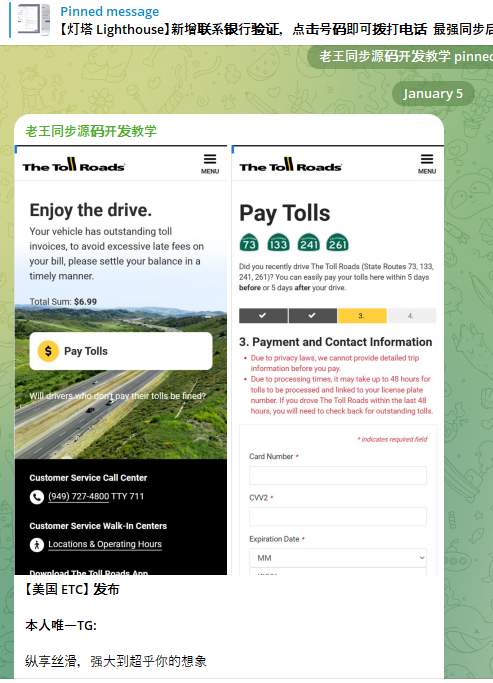

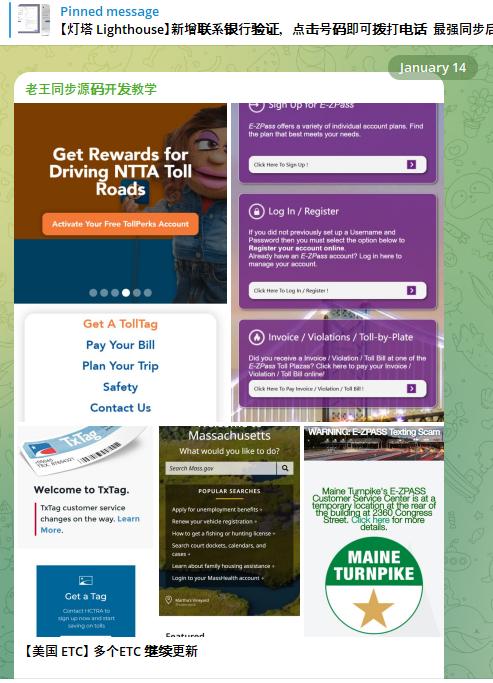

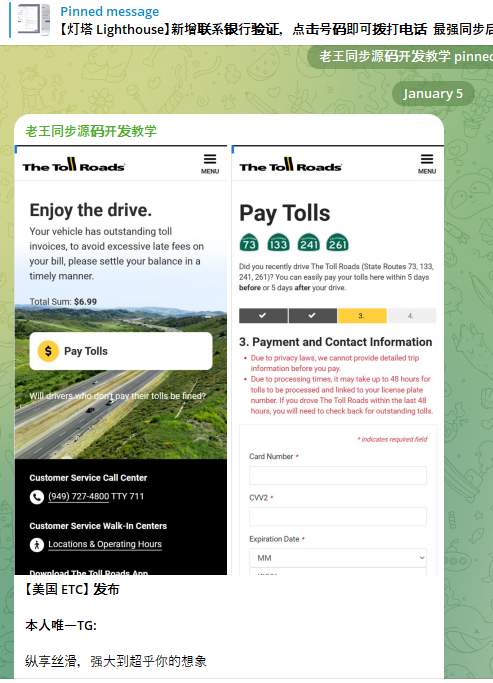

A component of the Chinese phishing kit Lighthouse made to target customers of The Toll Roads, which refers to several state routes through Orange County, Calif.

Lighthouse is one of several prolific phishing-as-a-service operations known as the “Smishing Triad,” and collectively they are responsible for sending millions of text messages that spoof the U.S. Postal Service to supposedly collect some outstanding delivery fee, or that pretend to be a local toll road operator warning of a delinquent toll fee. More recently, Lighthouse has been used to spoof e-commerce websites, financial institutions and brokerage firms.

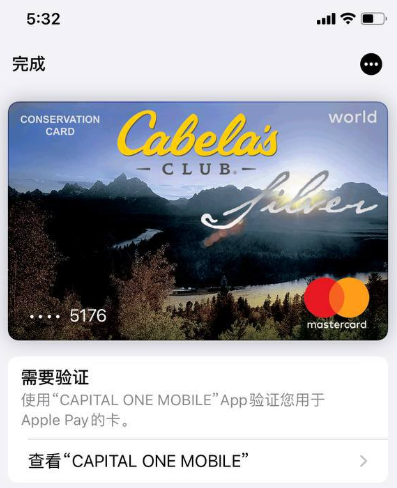

Regardless of the text message lure or brand used, the basic scam remains the same: After the visitor enters their payment information, the phishing site will automatically attempt to enroll the card as a mobile wallet from Apple or Google. The phishing site then tells the visitor that their bank is going to verify the transaction by sending a one-time code that needs to be entered into the payment page before the transaction can be completed.

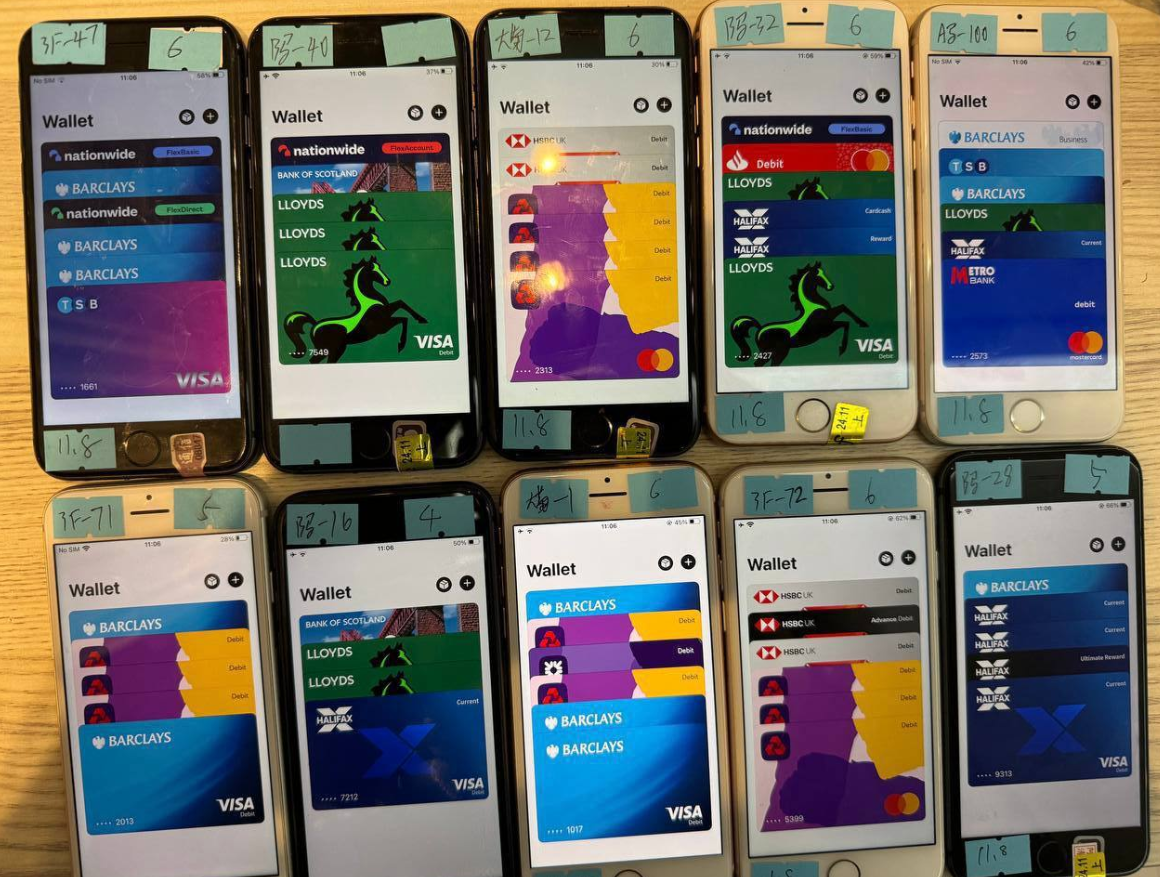

If the recipient provides that one-time code, the scammers can link the victim’s card data to a mobile wallet on a device that they control. Researchers say the fraudsters usually load several stolen wallets onto each mobile device, and wait 7-10 days after that enrollment before selling the phones or using them for fraud.

Google called the scale of the Lighthouse phishing attacks “staggering.” A May 2025 report from Silent Push found the domains used by the Smishing Triad are rotated frequently, with approximately 25,000 phishing domains active during any 8-day period.

Google’s lawsuit alleges the purveyors of Lighthouse violated the company’s trademarks by including Google’s logos on countless phishing websites. The complaint says Lighthouse offers over 600 templates for phishing websites of more than 400 entities, and that Google’s logos were featured on at least a quarter of those templates.

Google is also pursuing Lighthouse under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, saying the Lighthouse phishing enterprise encompasses several connected threat actor groups that work together to design and implement complex criminal schemes targeting the general public.

According to Google, those threat actor teams include a “developer group” that supplies the phishing software and templates; a “data broker group” that provides a list of targets; a “spammer group” that provides the tools to send fraudulent text messages in volume; a “theft group,” in charge of monetizing the phished information; and an “administrative group,” which runs their Telegram support channels and discussion groups designed to facilitate collaboration and recruit new members.

“While different members of the Enterprise may play different roles in the Schemes, they all collaborate to execute phishing attacks that rely on the Lighthouse software,” Google’s complaint alleges. “None of the Enterprise’s Schemes can generate revenue without collaboration and cooperation among the members of the Enterprise. All of the threat actor groups are connected to one another through historical and current business ties, including through their use of Lighthouse and the online community supporting its use, which exists on both YouTube and Telegram channels.”

Silent Push’s May report observed that the Smishing Triad boasts it has “300+ front desk staff worldwide” involved in Lighthouse, staff that is mainly used to support various aspects of the group’s fraud and cash-out schemes.

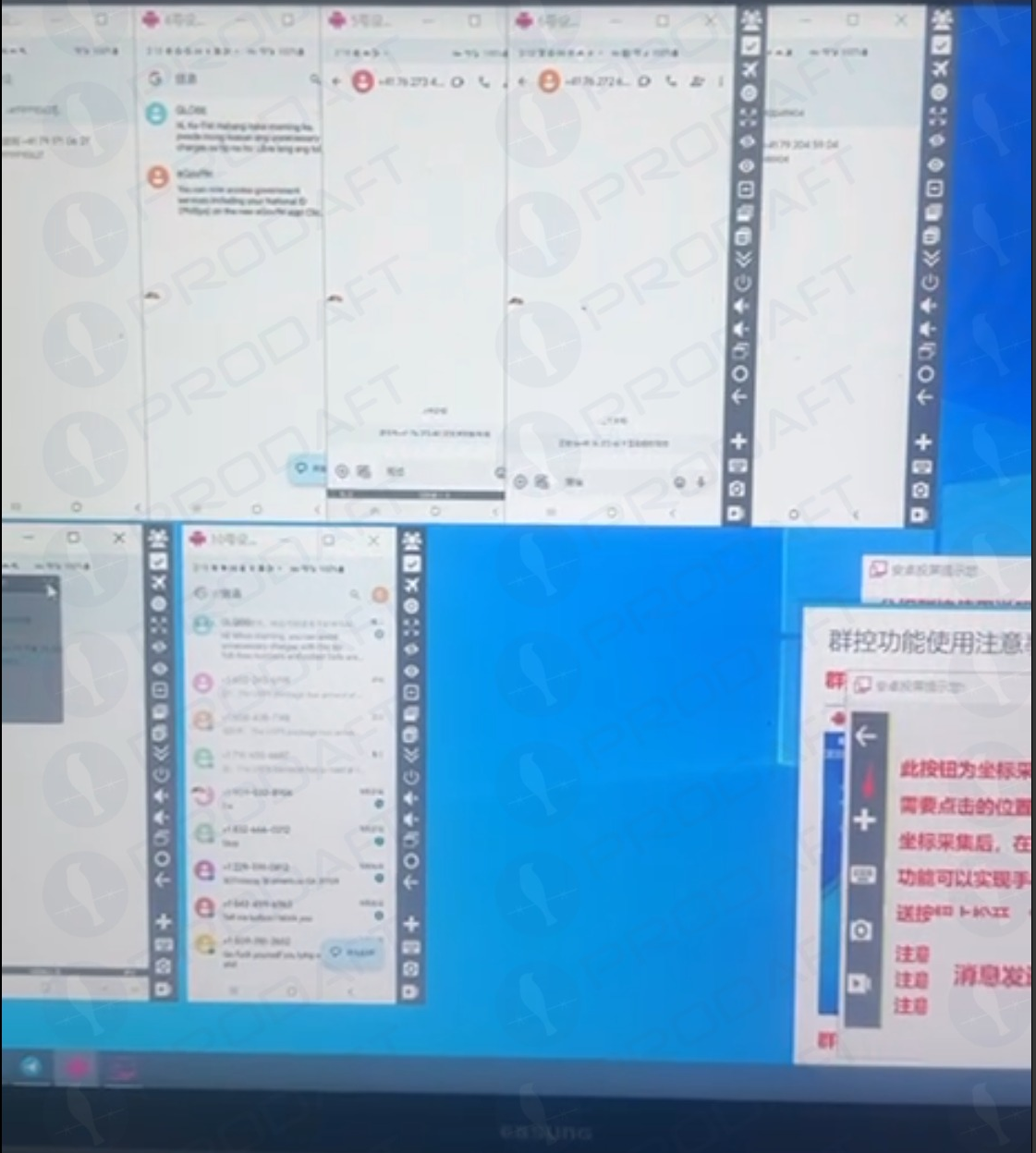

An image shared by an SMS phishing group shows a panel of mobile phones responsible for mass-sending phishing messages. These panels require a live operator because the one-time codes being shared by phishing victims must be used quickly as they generally expire within a few minutes.

Google alleges that in addition to blasting out text messages spoofing known brands, Lighthouse makes it easy for customers to mass-create fake e-commerce websites that are advertised using Google Ads accounts (and paid for with stolen credit cards). These phony merchants collect payment card information at checkout, and then prompt the customer to expect and share a one-time code sent from their financial institution.

Once again, that one-time code is being sent by the bank because the fake e-commerce site has just attempted to enroll the victim’s payment card data in a mobile wallet. By the time a victim understands they will likely never receive the item they just purchased from the fake e-commerce shop, the scammers have already run through hundreds of dollars in fraudulent charges, often at high-end electronics stores or jewelers.

Ford Merrill works in security research at SecAlliance, a CSIS Security Group company, and he’s been tracking Chinese SMS phishing groups for several years. Merrill said many Lighthouse customers are now using the phishing kit to erect fake e-commerce websites that are advertised on Google and Meta platforms.

“You find this shop by searching for a particular product online or whatever, and you think you’re getting a good deal,” Merrill said. “But of course you never receive the product, and they will phish that one-time code at checkout.”

Merrill said some of the phishing templates include payment buttons for services like PayPal, and that victims who choose to pay through PayPal can also see their PayPal accounts hijacked.

A fake e-commerce site from the Smishing Triad spoofing PayPal on a mobile device.

“The main advantage of the fake e-commerce site is that it doesn’t require them to send out message lures,” Merrill said, noting that the fake vendor sites have more staying power than traditional phishing sites because it takes far longer for them to be flagged for fraud.

Merrill said Google’s legal action may temporarily disrupt the Lighthouse operators, and could make it easier for U.S. federal authorities to bring criminal charges against the group. But he said the Chinese mobile phishing market is so lucrative right now that it’s difficult to imagine a popular phishing service voluntarily turning out the lights.

Merrill said Google’s lawsuit also can help lay the groundwork for future disruptive actions against Lighthouse and other phishing-as-a-service entities that are operating almost entirely on Chinese networks. According to Silent Push, a majority of the phishing sites created with these kits are sitting at two Chinese hosting companies: Tencent (AS132203) and Alibaba (AS45102).

“Once Google has a default judgment against the Lighthouse guys in court, theoretically they could use that to go to Alibaba and Tencent and say, ‘These guys have been found guilty, here are their domains and IP addresses, we want you to shut these down or we’ll include you in the case.'”

If Google can bring that kind of legal pressure consistently over time, Merrill said, they might succeed in increasing costs for the phishers and more frequently disrupting their operations.

“If you take all of these Chinese phishing kit developers, I have to believe it’s tens of thousands of Chinese-speaking people involved,” he said. “The Lighthouse guys will probably burn down their Telegram channels and disappear for a while. They might call it something else or redevelop their service entirely. But I don’t believe for a minute they’re going to close up shop and leave forever.”

China-based purveyors of SMS phishing kits are enjoying remarkable success converting phished payment card data into mobile wallets from Apple and Google. Until recently, the so-called “Smishing Triad” mainly impersonated toll road operators and shipping companies. But experts say these groups are now directly targeting customers of international financial institutions, while dramatically expanding their cybercrime infrastructure and support staff.

An image of an iPhone device farm shared on Telegram by one of the Smishing Triad members. Image: Prodaft.

If you own a mobile device, the chances are excellent that at some point in the past two years you’ve received at least one instant message that warns of a delinquent toll road fee, or a wayward package from the U.S. Postal Service (USPS). Those who click the promoted link are brought to a website that spoofs the USPS or a local toll road operator and asks for payment card information.

The site will then complain that the visitor’s bank needs to “verify” the transaction by sending a one-time code via SMS. In reality, the bank is sending that code to the mobile number on file for their customer because the fraudsters have just attempted to enroll that victim’s card details into a mobile wallet.

If the visitor supplies that one-time code, their payment card is then added to a new mobile wallet on an Apple or Google device that is physically controlled by the phishers. The phishing gangs typically load multiple stolen cards to digital wallets on a single Apple or Android device, and then sell those phones in bulk to scammers who use them for fraudulent e-commerce and tap-to-pay transactions.

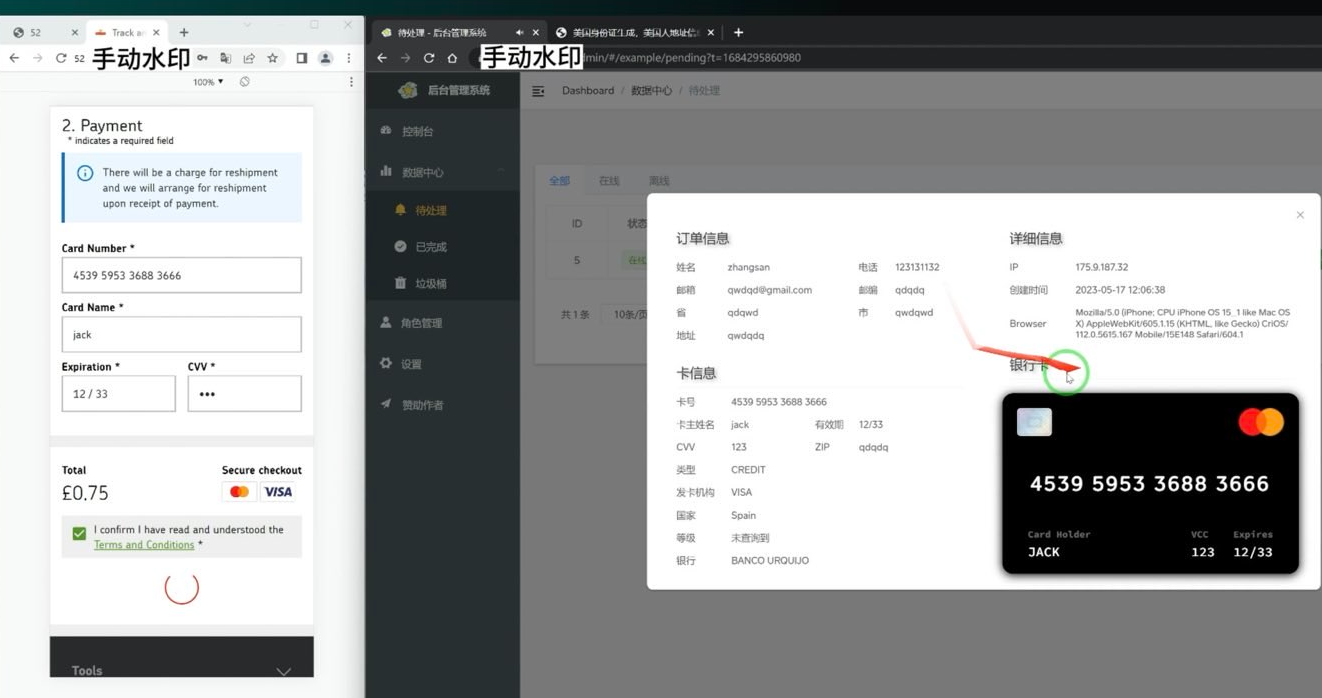

A screenshot of the administrative panel for a smishing kit. On the left is the (test) data entered at the phishing site. On the right we can see the phishing kit has superimposed the supplied card number onto an image of a payment card. When the phishing kit scans that created card image into Apple or Google Pay, it triggers the victim’s bank to send a one-time code. Image: Ford Merrill.

The moniker “Smishing Triad” comes from Resecurity, which was among the first to report in August 2023 on the emergence of three distinct mobile phishing groups based in China that appeared to share some infrastructure and innovative phishing techniques. But it is a bit of a misnomer because the phishing lures blasted out by these groups are not SMS or text messages in the conventional sense.

Rather, they are sent via iMessage to Apple device users, and via RCS on Google Android devices. Thus, the missives bypass the mobile phone networks entirely and enjoy near 100 percent delivery rate (at least until Apple and Google suspend the spammy accounts).

In a report published on March 24, the Swiss threat intelligence firm Prodaft detailed the rapid pace of innovation coming from the Smishing Triad, which it characterizes as a loosely federated group of Chinese phishing-as-a-service operators with names like Darcula, Lighthouse, and the Xinxin Group.

Prodaft said they’re seeing a significant shift in the underground economy, particularly among Chinese-speaking threat actors who have historically operated in the shadows compared to their Russian-speaking counterparts.

“Chinese-speaking actors are introducing innovative and cost-effective systems, enabling them to target larger user bases with sophisticated services,” Prodaft wrote. “Their approach marks a new era in underground business practices, emphasizing scalability and efficiency in cybercriminal operations.”

A new report from researchers at the security firm SilentPush finds the Smishing Triad members have expanded into selling mobile phishing kits targeting customers of global financial institutions like CitiGroup, MasterCard, PayPal, Stripe, and Visa, as well as banks in Canada, Latin America, Australia and the broader Asia-Pacific region.

Phishing lures from the Smishing Triad spoofing PayPal. Image: SilentPush.

SilentPush found the Smishing Triad now spoofs recognizable brands in a variety of industry verticals across at least 121 countries and a vast number of industries, including the postal, logistics, telecommunications, transportation, finance, retail and public sectors.

According to SilentPush, the domains used by the Smishing Triad are rotated frequently, with approximately 25,000 phishing domains active during any 8-day period and a majority of them sitting at two Chinese hosting companies: Tencent (AS132203) and Alibaba (AS45102).

“With nearly two-thirds of all countries in the world targeted by [the] Smishing Triad, it’s safe to say they are essentially targeting every country with modern infrastructure outside of Iran, North Korea, and Russia,” SilentPush wrote. “Our team has observed some potential targeting in Russia (such as domains that mentioned their country codes), but nothing definitive enough to indicate Russia is a persistent target. Interestingly, even though these are Chinese threat actors, we have seen instances of targeting aimed at Macau and Hong Kong, both special administrative regions of China.”

SilentPush’s Zach Edwards said his team found a vulnerability that exposed data from one of the Smishing Triad’s phishing pages, which revealed the number of visits each site received each day across thousands of phishing domains that were active at the time. Based on that data, SilentPush estimates those phishing pages received well more than a million visits within a 20-day time span.

The report notes the Smishing Triad boasts it has “300+ front desk staff worldwide” involved in one of their more popular phishing kits — Lighthouse — staff that is mainly used to support various aspects of the group’s fraud and cash-out schemes.

The Smishing Triad members maintain their own Chinese-language sales channels on Telegram, which frequently offer videos and photos of their staff hard at work. Some of those images include massive walls of phones used to send phishing messages, with human operators seated directly in front of them ready to receive any time-sensitive one-time codes.

As noted in February’s story How Phished Data Turns Into Apple and Google Wallets, one of those cash-out schemes involves an Android app called Z-NFC, which can relay a valid NFC transaction from one of these compromised digital wallets to anywhere in the world. For a $500 month subscription, the customer can wave their phone at any payment terminal that accepts Apple or Google pay, and the app will relay an NFC transaction over the Internet from a stolen wallet on a phone in China.

Chinese nationals were recently busted trying to use these NFC apps to buy high-end electronics in Singapore. And in the United States, authorities in California and Tennessee arrested Chinese nationals accused of using NFC apps to fraudulently purchase gift cards from retailers.

The Prodaft researchers said they were able to find a previously undocumented backend management panel for Lucid, a smishing-as-a-service operation tied to the XinXin Group. The panel included victim figures that suggest the smishing campaigns maintain an average success rate of approximately five percent, with some domains receiving over 500 visits per week.

“In one observed instance, a single phishing website captured 30 credit card records from 550 victim interactions over a 7-day period,” Prodaft wrote.

Prodaft’s report details how the Smishing Triad has achieved such success in sending their spam messages. For example, one phishing vendor appears to send out messages using dozens of Android device emulators running in parallel on a single machine.

Phishers using multiple virtualized Android devices to orchestrate and distribute RCS-based scam campaigns. Image: Prodaft.

According to Prodaft, the threat actors first acquire phone numbers through various means including data breaches, open-source intelligence, or purchased lists from underground markets. They then exploit technical gaps in sender ID validation within both messaging platforms.

“For iMessage, this involves creating temporary Apple IDs with impersonated display names, while RCS exploitation leverages carrier implementation inconsistencies in sender verification,” Prodaft wrote. “Message delivery occurs through automated platforms using VoIP numbers or compromised credentials, often deployed in precisely timed multi-wave campaigns to maximize effectiveness.

In addition, the phishing links embedded in these messages use time-limited single-use URLs that expire or redirect based on device fingerprinting to evade security analysis, they found.

“The economics strongly favor the attackers, as neither RCS nor iMessage messages incur per-message costs like traditional SMS, enabling high-volume campaigns at minimal operational expense,” Prodaft continued. “The overlap in templates, target pools, and tactics among these platforms underscores a unified threat landscape, with Chinese-speaking actors driving innovation in the underground economy. Their ability to scale operations globally and evasion techniques pose significant challenges to cybersecurity defenses.”

Ford Merrill works in security research at SecAlliance, a CSIS Security Group company. Merrill said he’s observed at least one video of a Windows binary that wraps a Chrome executable and can be used to load in target phone numbers and blast messages via RCS, iMessage, Amazon, Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp.

“The evidence we’ve observed suggests the ability for a single device to send approximately 100 messages per second,” Merrill said. “We also believe that there is capability to source country specific SIM cards in volume that allow them to register different online accounts that require validation with specific country codes, and even make those SIM cards available to the physical devices long-term so that services that rely on checks of the validity of the phone number or SIM card presence on a mobile network are thwarted.”

Experts say this fast-growing wave of card fraud persists because far too many financial institutions still default to sending one-time codes via SMS for validating card enrollment in mobile wallets from Apple or Google. KrebsOnSecurity interviewed multiple security executives at non-U.S. financial institutions who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the press. Those banks have since done away with SMS-based one-time codes and are now requiring customers to log in to the bank’s mobile app before they can link their card to a digital wallet.

Carding — the underground business of stealing, selling and swiping stolen payment card data — has long been the dominion of Russia-based hackers. Happily, the broad deployment of more secure chip-based payment cards in the United States has weakened the carding market. But a flurry of innovation from cybercrime groups in China is breathing new life into the carding industry, by turning phished card data into mobile wallets that can be used online and at main street stores.

An image from one Chinese phishing group’s Telegram channel shows various toll road phish kits available.

If you own a mobile phone, the chances are excellent that at some point in the past two years it has received at least one phishing message that spoofs the U.S. Postal Service to supposedly collect some outstanding delivery fee, or an SMS that pretends to be a local toll road operator warning of a delinquent toll fee.

These messages are being sent through sophisticated phishing kits sold by several cybercriminals based in mainland China. And they are not traditional SMS phishing or “smishing” messages, as they bypass the mobile networks entirely. Rather, the missives are sent through the Apple iMessage service and through RCS, the functionally equivalent technology on Google phones.

People who enter their payment card data at one of these sites will be told their financial institution needs to verify the small transaction by sending a one-time passcode to the customer’s mobile device. In reality, that code will be sent by the victim’s financial institution to verify that the user indeed wishes to link their card information to a mobile wallet.

If the victim then provides that one-time code, the phishers will link the card data to a new mobile wallet from Apple or Google, loading the wallet onto a mobile phone that the scammers control.

Ford Merrill works in security research at SecAlliance, a CSIS Security Group company. Merrill has been studying the evolution of several China-based smishing gangs, and found that most of them feature helpful and informative video tutorials in their sales accounts on Telegram. Those videos show the thieves are loading multiple stolen digital wallets on a single mobile device, and then selling those phones in bulk for hundreds of dollars apiece.

“Who says carding is dead?,” said Merrill, who presented about his findings at the M3AAWG security conference in Lisbon earlier today. “This is the best mag stripe cloning device ever. This threat actor is saying you need to buy at least 10 phones, and they’ll air ship them to you.”

One promotional video shows stacks of milk crates stuffed full of phones for sale. A closer inspection reveals that each phone is affixed with a handwritten notation that typically references the date its mobile wallets were added, the number of wallets on the device, and the initials of the seller.

An image from the Telegram channel for a popular Chinese smishing kit vendor shows 10 mobile phones for sale, each loaded with 4-6 digital wallets from different UK financial institutions.

Merrill said one common way criminal groups in China are cashing out with these stolen mobile wallets involves setting up fake e-commerce businesses on Stripe or Zelle and running transactions through those entities — often for amounts totaling between $100 and $500.

Merrill said that when these phishing groups first began operating in earnest two years ago, they would wait between 60 to 90 days before selling the phones or using them for fraud. But these days that waiting period is more like just seven to ten days, he said.

“When they first installed this, the actors were very patient,” he said. “Nowadays, they only wait like 10 days before [the wallets] are hit hard and fast.”

Criminals also can cash out mobile wallets by obtaining real point-of-sale terminals and using tap-to-pay on phone after phone. But they also offer a more cutting-edge mobile fraud technology: Merrill found that at least one of the Chinese phishing groups sells an Android app called “ZNFC” that can relay a valid NFC transaction to anywhere in the world. The user simply waves their phone at a local payment terminal that accepts Apple or Google pay, and the app relays an NFC transaction over the Internet from a phone in China.

“The software can work from anywhere in the world,” Merrill said. “These guys provide the software for $500 a month, and it can relay both NFC enabled tap-to-pay as well as any digital wallet. They even have 24-hour support.”

The rise of so-called “ghost tap” mobile software was first documented in November 2024 by security experts at ThreatFabric. Andy Chandler, the company’s chief commercial officer, said their researchers have since identified a number of criminal groups from different regions of the world latching on to this scheme.

Chandler said those include organized crime gangs in Europe that are using similar mobile wallet and NFC attacks to take money out of ATMs made to work with smartphones.

“No one is talking about it, but we’re now seeing ten different methodologies using the same modus operandi, and none of them are doing it the same,” Chandler said. “This is much bigger than the banks are prepared to say.”

A November 2024 story in the Singapore daily The Straits Times reported authorities there arrested three foreign men who were recruited in their home countries via social messaging platforms, and given ghost tap apps with which to purchase expensive items from retailers, including mobile phones, jewelry, and gold bars.

“Since Nov 4, at least 10 victims who had fallen for e-commerce scams have reported unauthorised transactions totaling more than $100,000 on their credit cards for purchases such as electronic products, like iPhones and chargers, and jewelry in Singapore,” The Straits Times wrote, noting that in another case with a similar modus operandi, the police arrested a Malaysian man and woman on Nov 8.

Three individuals charged with using ghost tap software at an electronics store in Singapore. Image: The Straits Times.

According to Merrill, the phishing pages that spoof the USPS and various toll road operators are powered by several innovations designed to maximize the extraction of victim data.

For example, a would-be smishing victim might enter their personal and financial information, but then decide the whole thing is scam before actually submitting the data. In this case, anything typed into the data fields of the phishing page will be captured in real time, regardless of whether the visitor actually clicks the “submit” button.

Merrill said people who submit payment card data to these phishing sites often are then told their card can’t be processed, and urged to use a different card. This technique, he said, sometimes allows the phishers to steal more than one mobile wallet per victim.

Many phishing websites expose victim data by storing the stolen information directly on the phishing domain. But Merrill said these Chinese phishing kits will forward all victim data to a back-end database operated by the phishing kit vendors. That way, even when the smishing sites get taken down for fraud, the stolen data is still safe and secure.

Another important innovation is the use of mass-created Apple and Google user accounts through which these phishers send their spam messages. One of the Chinese phishing groups posted images on their Telegram sales channels showing how these robot Apple and Google accounts are loaded onto Apple and Google phones, and arranged snugly next to each other in an expansive, multi-tiered rack that sits directly in front of the phishing service operator.

The ashtray says: You’ve been phishing all night.

In other words, the smishing websites are powered by real human operators as long as new messages are being sent. Merrill said the criminals appear to send only a few dozen messages at a time, likely because completing the scam takes manual work by the human operators in China. After all, most one-time codes used for mobile wallet provisioning are generally only good for a few minutes before they expire.

Notably, none of the phishing sites spoofing the toll operators or postal services will load in a regular Web browser; they will only render if they detect that a visitor is coming from a mobile device.

“One of the reasons they want you to be on a mobile device is they want you to be on the same device that is going to receive the one-time code,” Merrill said. “They also want to minimize the chances you will leave. And if they want to get that mobile tokenization and grab your one-time code, they need a live operator.”

Merrill found the Chinese phishing kits feature another innovation that makes it simple for customers to turn stolen card details into a mobile wallet: They programmatically take the card data supplied by the phishing victim and convert it into a digital image of a real payment card that matches that victim’s financial institution. That way, attempting to enroll a stolen card into Apple Pay, for example, becomes as easy as scanning the fabricated card image with an iPhone.

An ad from a Chinese SMS phishing group’s Telegram channel showing how the service converts stolen card data into an image of the stolen card.

“The phone isn’t smart enough to know whether it’s a real card or just an image,” Merrill said. “So it scans the card into Apple Pay, which says okay we need to verify that you’re the owner of the card by sending a one-time code.”

How profitable are these mobile phishing kits? The best guess so far comes from data gathered by other security researchers who’ve been tracking these advanced Chinese phishing vendors.

In August 2023, the security firm Resecurity discovered a vulnerability in one popular Chinese phish kit vendor’s platform that exposed the personal and financial data of phishing victims. Resecurity dubbed the group the Smishing Triad, and found the gang had harvested 108,044 payment cards across 31 phishing domains (3,485 cards per domain).

In August 2024, security researcher Grant Smith gave a presentation at the DEFCON security conference about tracking down the Smishing Triad after scammers spoofing the U.S. Postal Service duped his wife. By identifying a different vulnerability in the gang’s phishing kit, Smith said he was able to see that people entered 438,669 unique credit cards in 1,133 phishing domains (387 cards per domain).

Based on his research, Merrill said it’s reasonable to expect between $100 and $500 in losses on each card that is turned into a mobile wallet. Merrill said they observed nearly 33,000 unique domains tied to these Chinese smishing groups during the year between the publication of Resecurity’s research and Smith’s DEFCON talk.

Using a median number of 1,935 cards per domain and a conservative loss of $250 per card, that comes out to about $15 billion in fraudulent charges over a year.

Merrill was reluctant to say whether he’d identified additional security vulnerabilities in any of the phishing kits sold by the Chinese groups, noting that the phishers quickly fixed the vulnerabilities that were detailed publicly by Resecurity and Smith.

Adoption of touchless payments took off in the United States after the Coronavirus pandemic emerged, and many financial institutions in the United States were eager to make it simple for customers to link payment cards to mobile wallets. Thus, the authentication requirement for doing so defaulted to sending the customer a one-time code via SMS.

Experts say the continued reliance on one-time codes for onboarding mobile wallets has fostered this new wave of carding. KrebsOnSecurity interviewed a security executive from a large European financial institution who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the press.

That expert said the lag between the phishing of victim card data and its eventual use for fraud has left many financial institutions struggling to correlate the causes of their losses.

“That’s part of why the industry as a whole has been caught by surprise,” the expert said. “A lot of people are asking, how this is possible now that we’ve tokenized a plaintext process. We’ve never seen the volume of sending and people responding that we’re seeing with these phishers.”

To improve the security of digital wallet provisioning, some banks in Europe and Asia require customers to log in to the bank’s mobile app before they can link a digital wallet to their device.

Addressing the ghost tap threat may require updates to contactless payment terminals, to better identify NFC transactions that are being relayed from another device. But experts say it’s unrealistic to expect retailers will be eager to replace existing payment terminals before their expected lifespans expire.

And of course Apple and Google have an increased role to play as well, given that their accounts are being created en masse and used to blast out these smishing messages. Both companies could easily tell which of their devices suddenly have 7-10 different mobile wallets added from 7-10 different people around the world. They could also recommend that financial institutions use more secure authentication methods for mobile wallet provisioning.

Neither Apple nor Google responded to requests for comment on this story.

Residents across the United States are being inundated with text messages purporting to come from toll road operators like E-ZPass, warning that recipients face fines if a delinquent toll fee remains unpaid. Researchers say the surge in SMS spam coincides with new features added to a popular commercial phishing kit sold in China that makes it simple to set up convincing lures spoofing toll road operators in multiple U.S. states.

Last week, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) warned residents to be on the lookout for a new SMS phishing or “smishing” scam targeting users of EZDriveMA, MassDOT’s all electronic tolling program. Those who fall for the scam are asked to provide payment card data, and eventually will be asked to supply a one-time password sent via SMS or a mobile authentication app.

Reports of similar SMS phishing attacks against customers of other U.S. state-run toll facilities surfaced around the same time as the MassDOT alert. People in Florida reported receiving SMS phishing that spoofed Sunpass, Florida’s prepaid toll program.

This phishing module for spoofing MassDOT’s EZDrive toll system was offered on Jan. 10, 2025 by a China-based SMS phishing service called “Lighthouse.”

In Texas, residents said they received text messages about unpaid tolls with the North Texas Toll Authority. Similar reports came from readers in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Minnesota, and Washington. This is by no means a comprehensive list.

A new module from the Lighthouse SMS phishing kit released Jan. 14 targets customers of the North Texas Toll Authority (NTTA).

In each case, the emergence of these SMS phishing attacks coincided with the release of new phishing kit capabilities that closely mimic these toll operator websites as they appear on mobile devices. Notably, none of the phishing pages will even load unless the website detects that the visitor is coming from a mobile device.

Ford Merrill works in security research at SecAlliance, a CSIS Security Group company. Merrill said the volume of SMS phishing attacks spoofing toll road operators skyrocketed after the New Year, when at least one Chinese cybercriminal group known for selling sophisticated SMS phishing kits began offering new phishing pages designed to spoof toll operators in various U.S. states.

According to Merrill, multiple China-based cybercriminals are selling distinct SMS-based phishing kits that each have hundreds or thousands of customers. The ultimate goal of these kits, he said, is to phish enough information from victims that their payment cards can be added to mobile wallets and used to buy goods at physical stores, online, or to launder money through shell companies.

A component of the Chinese SMS phishing kit Lighthouse made to target customers of The Toll Roads, which refers to several state routes through Orange County, Calif.

Merrill said the different purveyors of these SMS phishing tools traditionally have impersonated shipping companies, customs authorities, and even governments with tax refund lures and visa or immigration renewal scams targeting people who may be living abroad or new to a country.

“What we’re seeing with these tolls scams is just a continuation of the Chinese smishing groups rotating from package redelivery schemes to toll road scams,” Merrill said. “Every one of us by now is sick and tired of receiving these package smishing attacks, so now it’s a new twist on an existing scam.”

In October 2023, KrebsOnSecurity wrote about a massive uptick in SMS phishing scams targeting U.S. Postal Service customers. That story revealed the surge was tied to innovations introduced by “Chenlun,” a mainland China-based proprietor of a popular phishing kit and service. At the time, Chenlun had just introduced new phishing pages made to impersonate postal services in the United States and at least a dozen other countries.

SMS phishing kits are hardly new, but Merrill said Chinese smishing groups recently have introduced innovations in deliverability, by more seamlessly integrating their spam messages with Apple’s iMessage technology, and with RCS, the equivalent “rich text” messaging capability built into Android devices.

“While traditional smishing kits relied heavily on SMS for delivery, nowadays the actors make heavy use of iMessage and RCS because telecom operators can’t filter them and they likely have a higher success rate with these delivery channels,” he said.

It remains unclear how the phishers have selected their targets, or from where their data may be sourced. A notice from MassDOT cautions that “the targeted phone numbers seem to be chosen at random and are not uniquely associated with an account or usage of toll roads.”

Indeed, one reader shared on Mastodon yesterday that they’d received one of these SMS phishing attacks spoofing a local toll operator, when they didn’t even own a vehicle.

Targeted or not, these phishing websites are dangerous because they are operated dynamically in real-time by criminals. If you receive one of these messages, just ignore it or delete it, but please do not visit the phishing site. The FBI asks that before you bin the missives, consider filing a complaint with the agency’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), including the phone number where the text originated, and the website listed within the text.

With a buzz, your phone lets you know you got a text. You take a peek. It’s from the U.S. Postal Service with a message about your package. Or is it? You might be looking at a smishing scam.

“Smishing” takes its form from two terms: SMS messaging and phishing. Effectively, smishing is a phishing attack on your phone. Scammers love these attacks year-round, and particularly so during holiday shopping rushes. The fact remains that we ship plenty of packages plenty often, and scammers use that to their advantage.

Smishing attacks try to slip into the other legitimate messages you get about shipments. The idea is that you might have a couple on the way and might mistake the smishing attack for a proper message. Scammers make them look and sound legit, posing as the U.S. Postal Service or other carriers like UPS, DHL, and FedEx.

New data from McAfee’s State of the Scamiverse 2025 report reveals that text and email scams are on the rise worldwide. The average American is targeted by more than 14 scams every day, including an average of 3 deepfake videos. This surge in scam activity shows that scammers are increasingly relying on mobile attacks, as 76% of all tax scam activity in 2024 targeted mobile users via text, often using URL shorteners to disguise fraudulent links.

To pull off these attacks, scammers send out text messages from random numbers saying that a delivery has an urgent transit issue. When a victim taps on the link in the text, it takes them to a form page that asks them to fill in their personal and financial info to “verify their purchase delivery.” With the form completed, the scammer can then exploit that info for financial gain.

However, scammers also use this phishing scheme to infect people’s devices with malware. For example, some users received links claiming to provide access to a supposed postal shipment. Instead, they were led to a domain that did nothing but infect their browser or phone with malware. Regardless of what route the hacker takes, these scams leave the user in a situation that compromises their smartphone and personal data.

While delivery alerts are a convenient way to track packages, it’s important to familiarize yourself with the signs of smishing scams. Doing so will help you safeguard your online security without sacrificing the convenience of your smartphone. To do just that, take these straightforward steps.

Go directly to the source.

Be skeptical of text messages from companies with peculiar requests or info that seems too good to be true. Be even more skeptical if the link looks different from what you’d expect from that sender — like a shortened link or a kit-bashed name like “fed-ex-delivery dot-com.” Instead of clicking on a link within the text, it’s best to go straight to the organization’s website to check on your delivery status or contact customer service.

Enable the feature on your mobile device that blocks certain texts.

Many spammers send texts from an internet service to hide their identities. You can combat this by using the feature on your mobile device that blocks texts sent from the internet or unknown users. For example, you can disable all potential spam messages from the Messages app on an Android device. Head to “Settings,” tap on “Spam protection,” and then enable it. On iPhones, head to “Settings” > “Messages” and flip the switch next to “Filter Unknown Senders.”

One caveat, though. This can block legitimate messages just as easily. Say you’re getting your car serviced. If you don’t have the shop’s number stored on your phone, their updates on your repair progress will get blocked as well.

Use mobile device protection.

Our McAfee Mobile Security puts up a great defense. Devices can be attacked by malware and other forms of malicious software. Our mobile security app offers peace of mind by protecting your identity, privacy, and device.

Protect your privacy and identity all around.

McAfee+ plans offer strong protection for your identity, privacy, and finances. All the things those smishers are after. It includes credit and identity monitoring, social privacy management, and a VPN, plus several transaction monitoring features. Together, they spot scams and give you the tools to stop them dead in their tracks.

And if the unfortunate happens, our Identity Theft Coverage & Restoration can get you on the path to recovery. It offers up to $2 million in coverage for legal fees, travel, and funds lost because of identity theft. Further, a licensed recovery pro can do the work for you, taking the necessary steps to repair your identity and credit.

The post How Not to Fall for Smishing Scams appeared first on McAfee Blog.