The sheer scope of cybercrime can be hard to fathom, even when you live and breathe it every day. It's not just the volume of data, but also the extent to which it replicates across criminal actors seeking to abuse it for their own gain, and to our detriment.

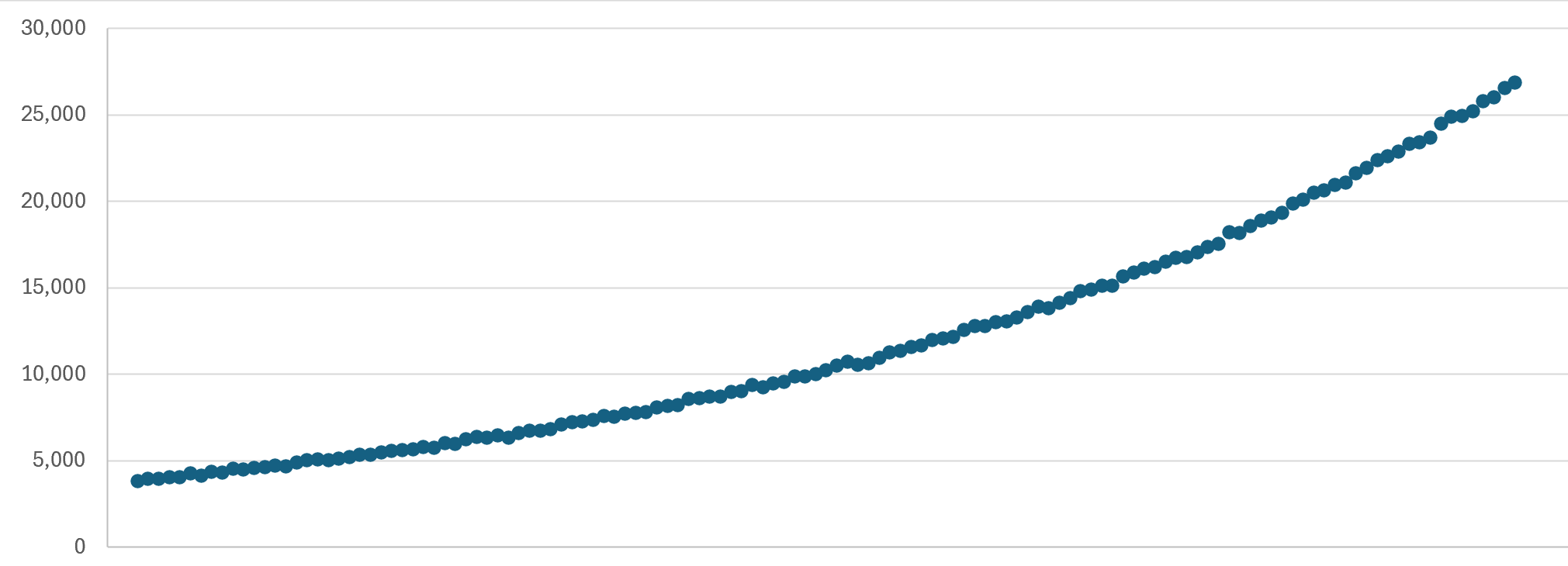

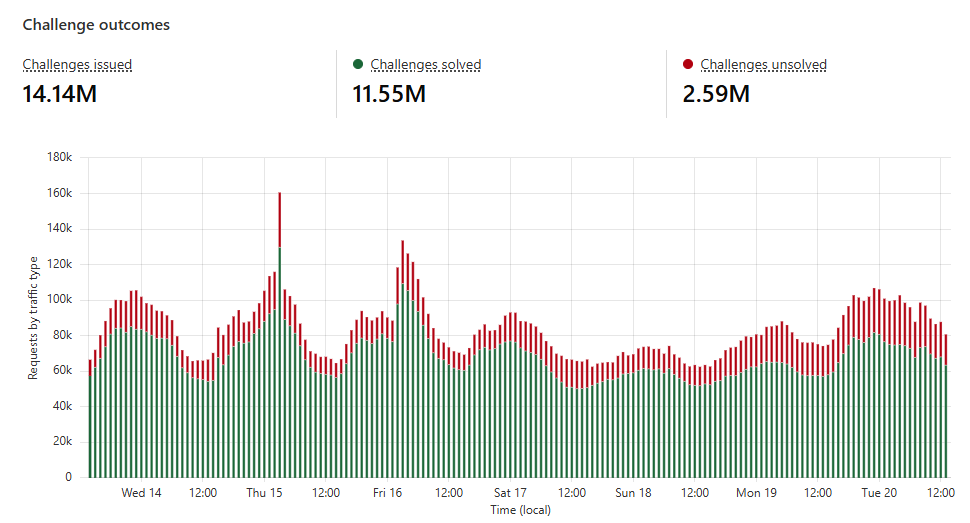

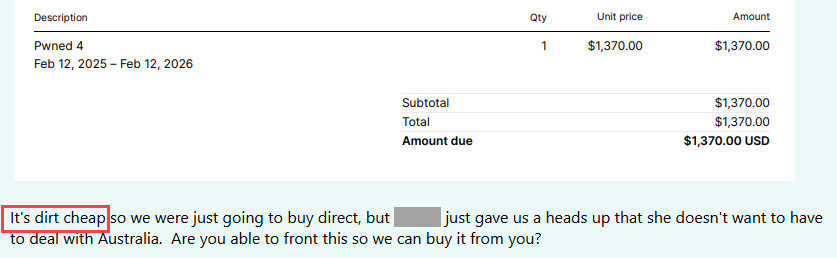

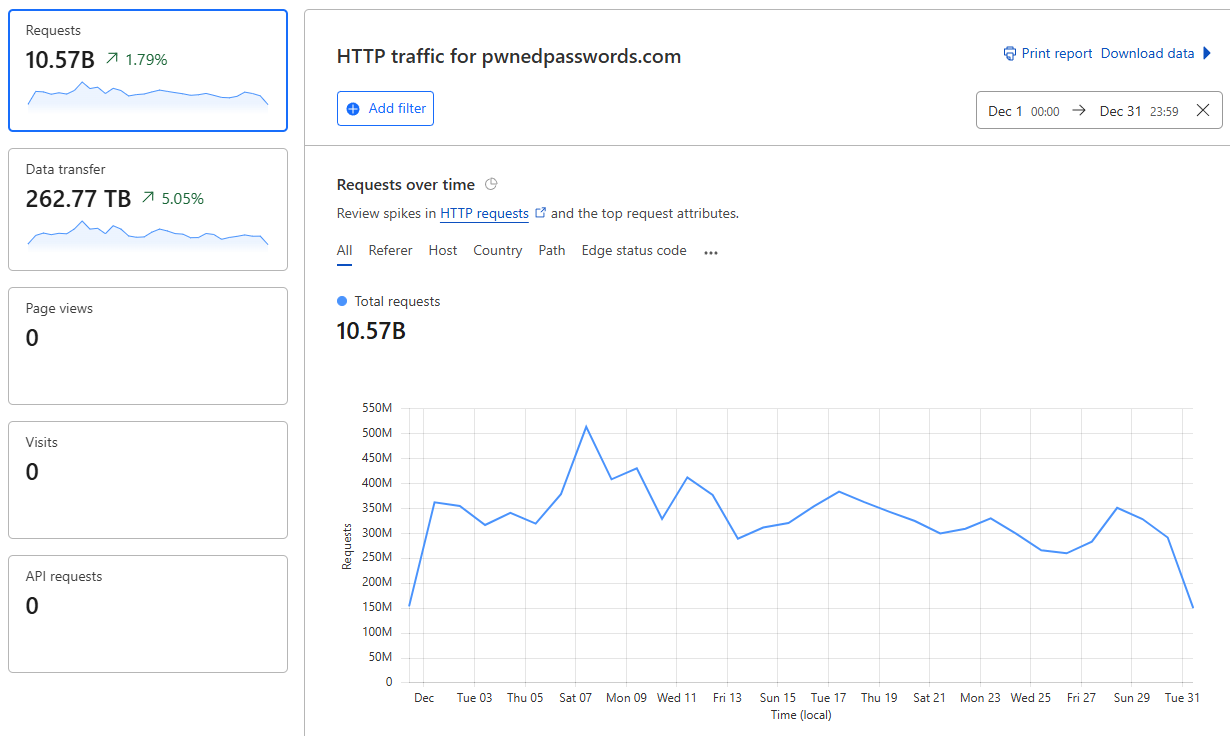

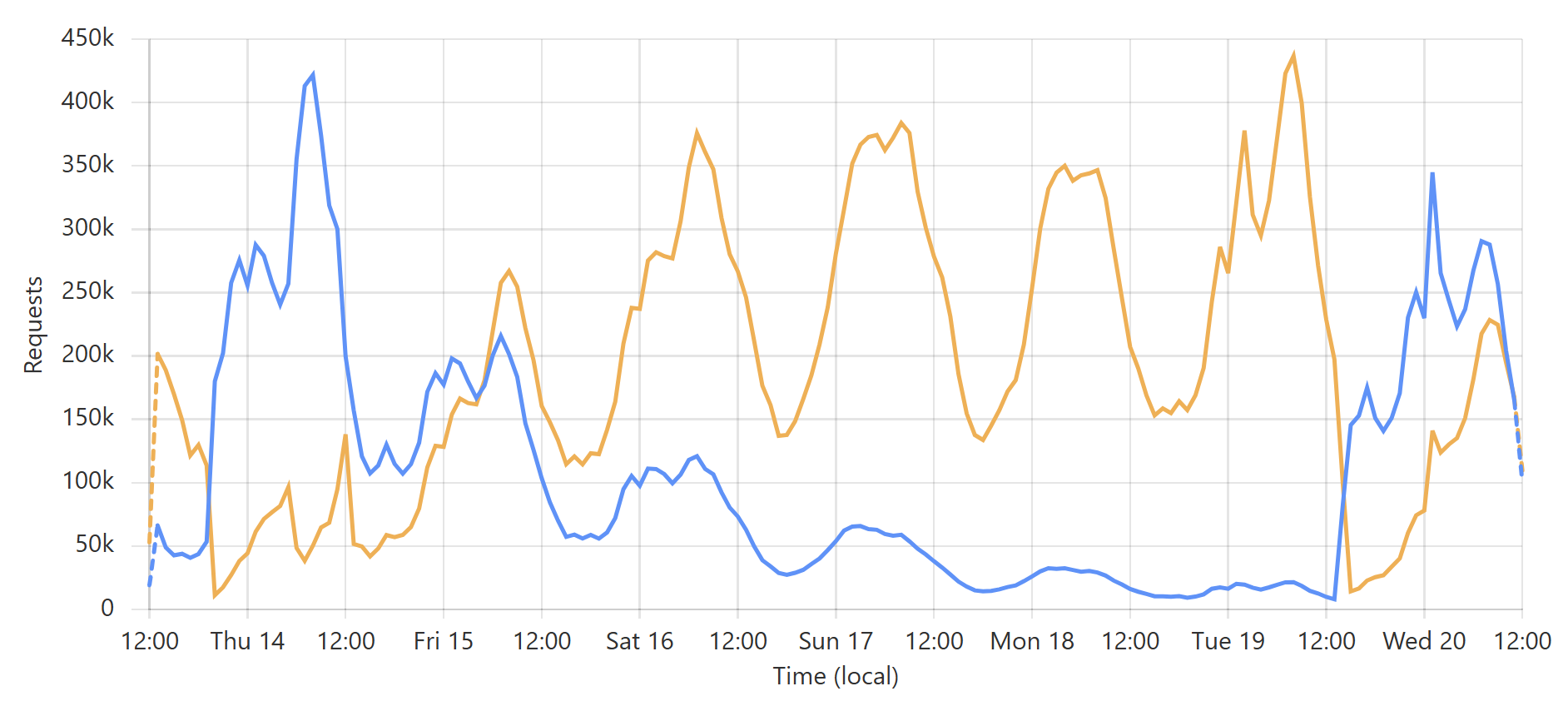

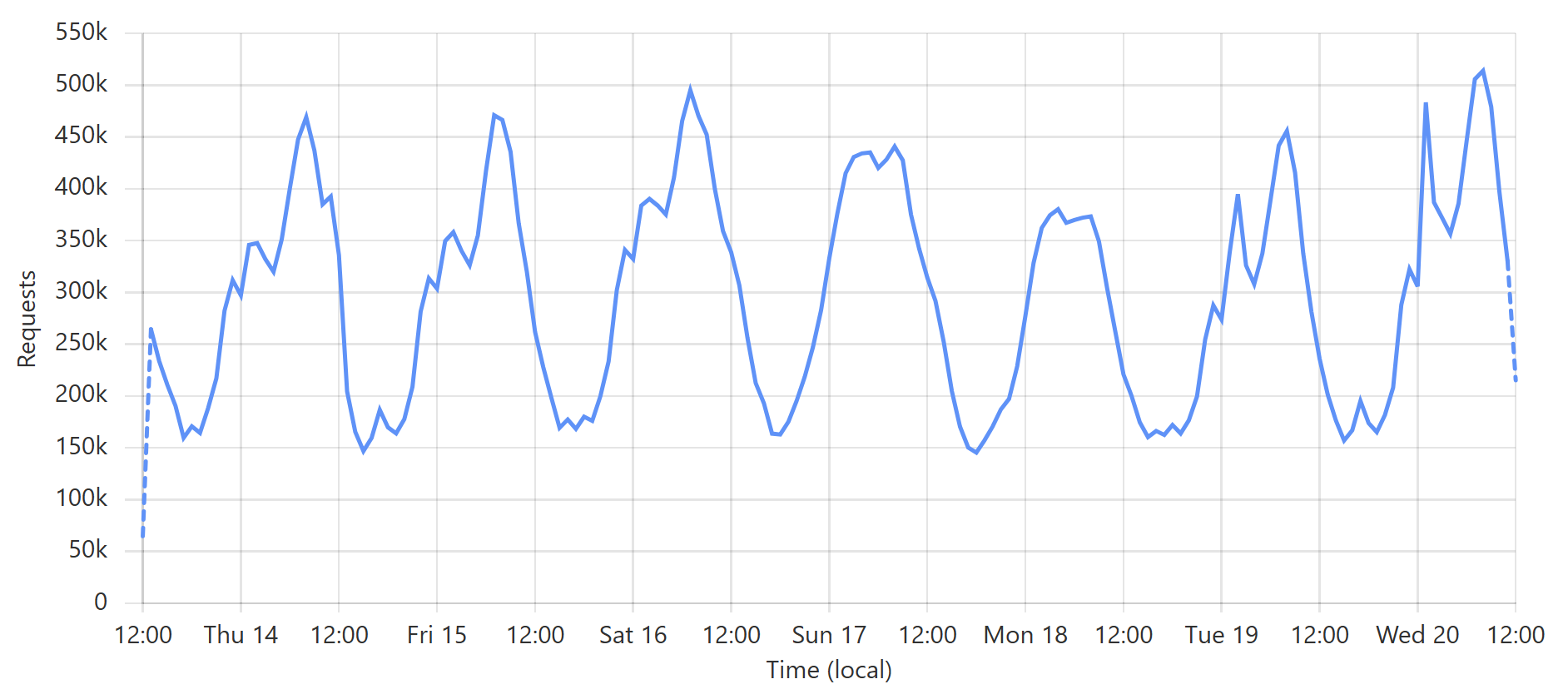

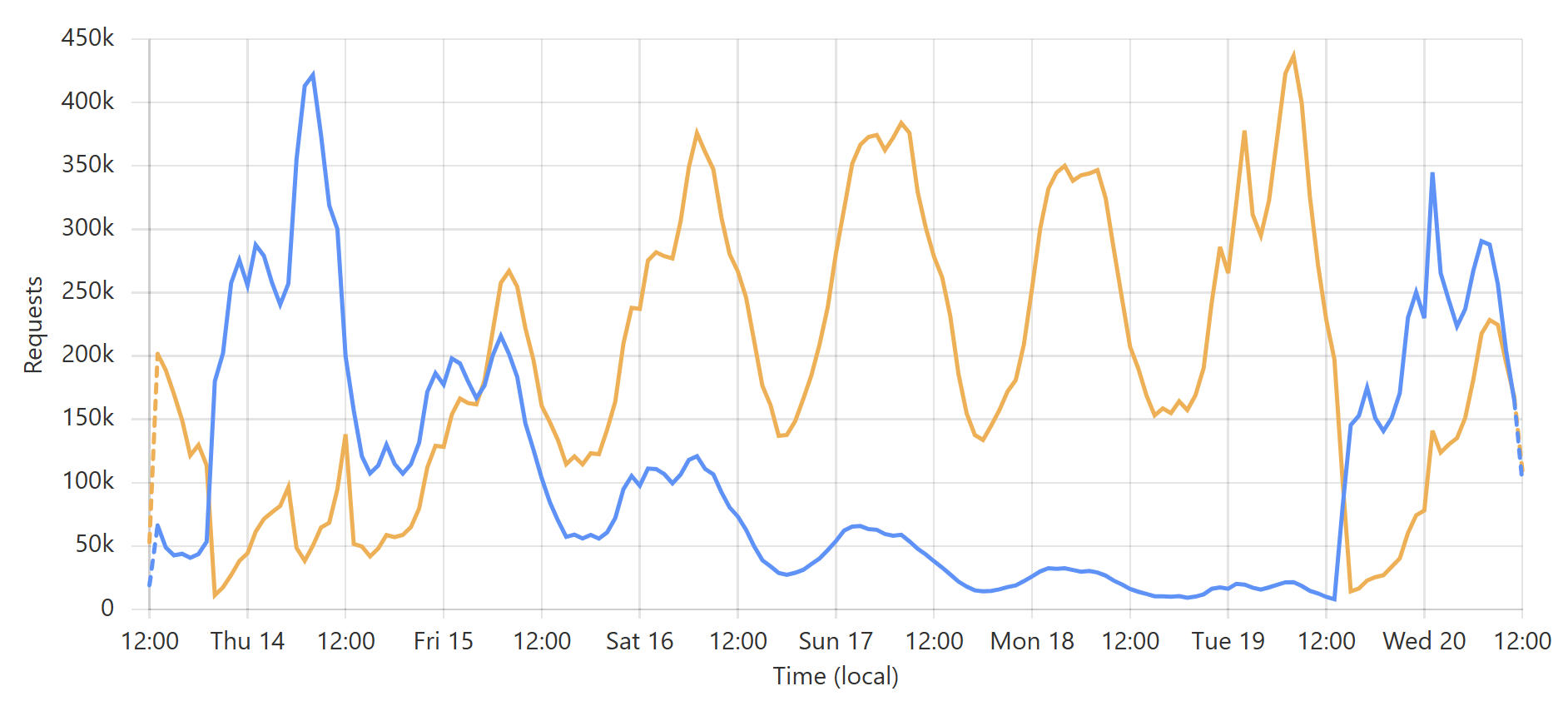

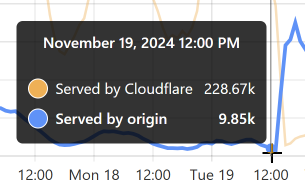

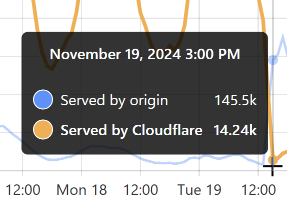

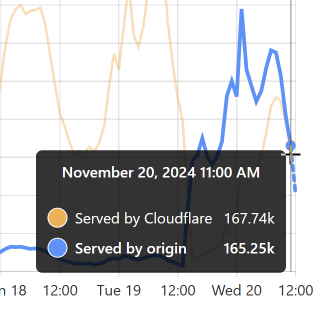

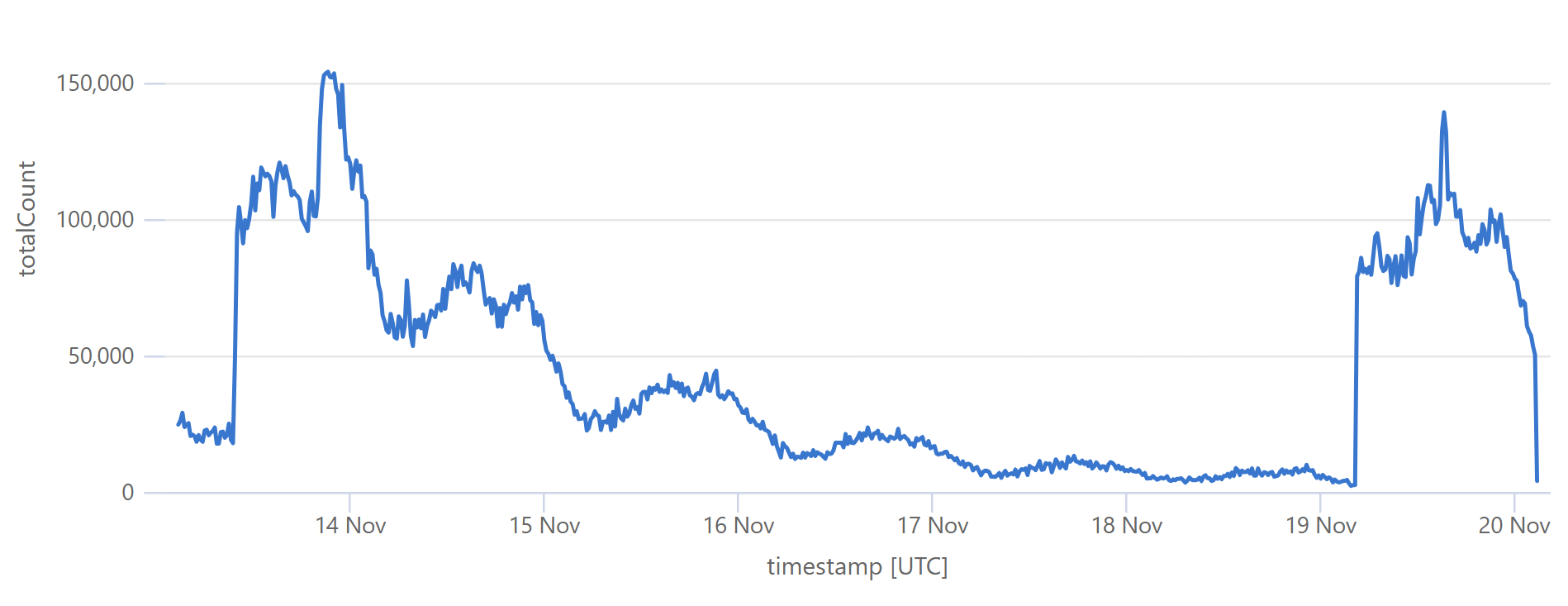

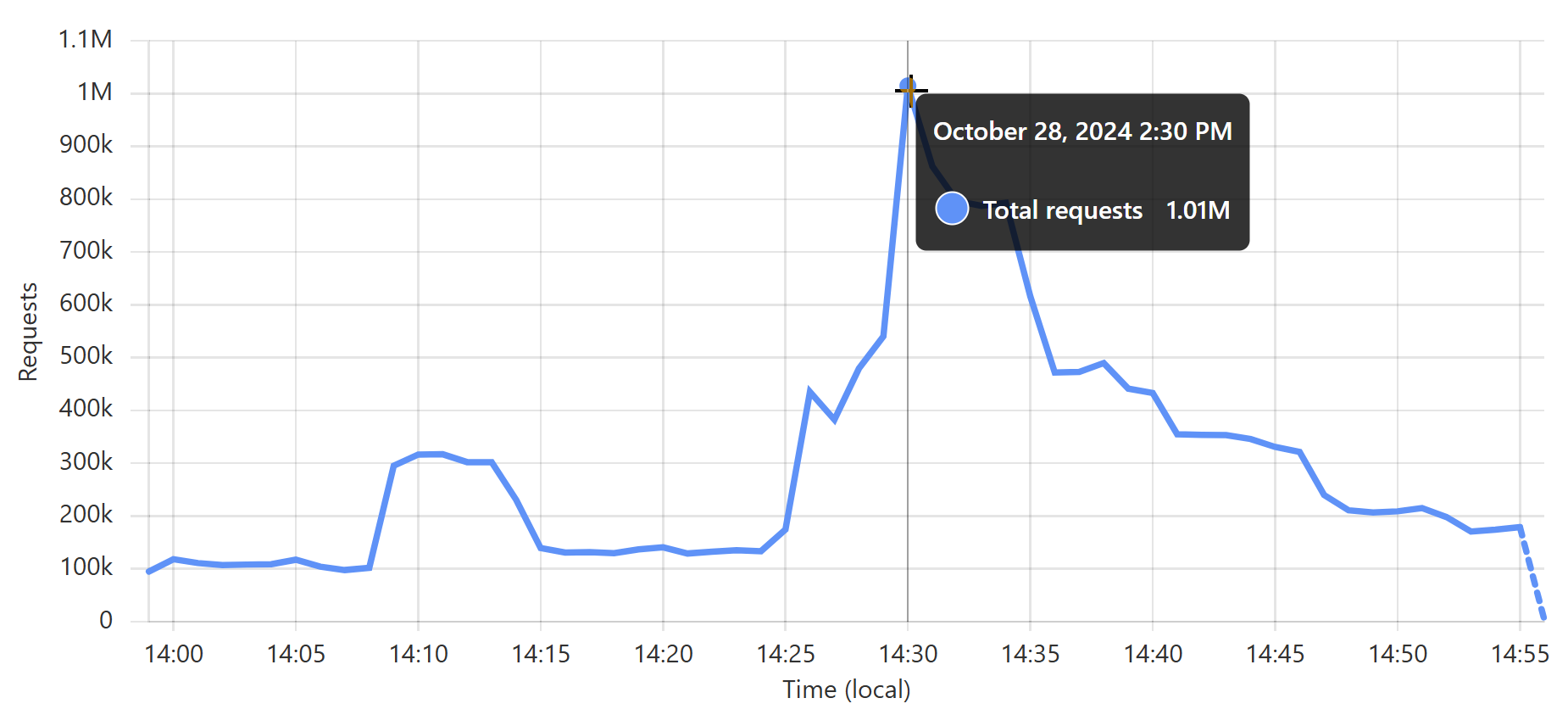

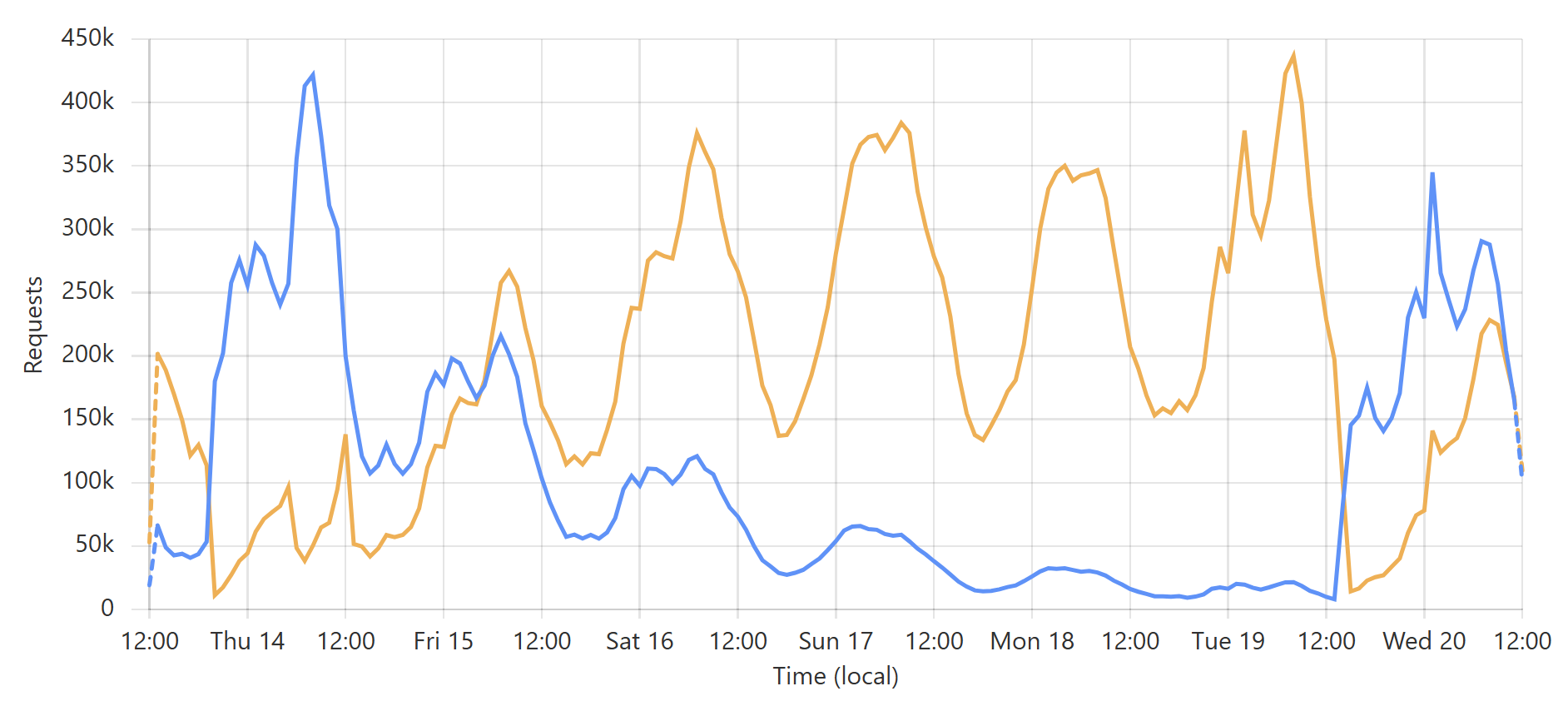

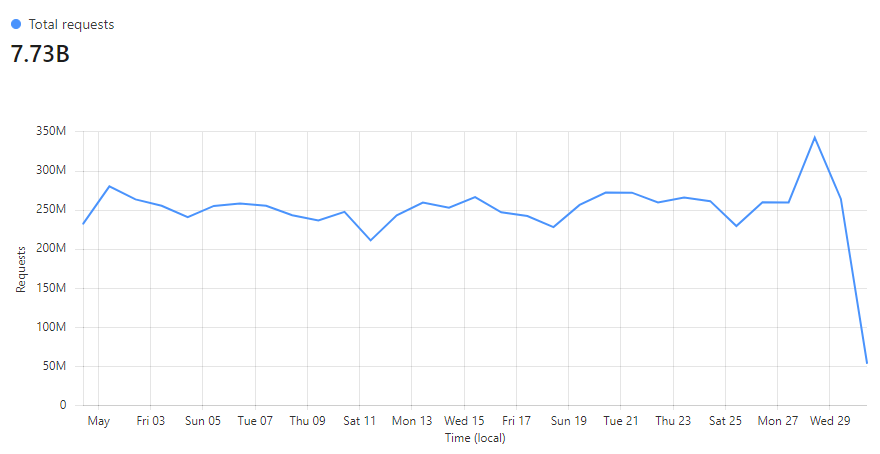

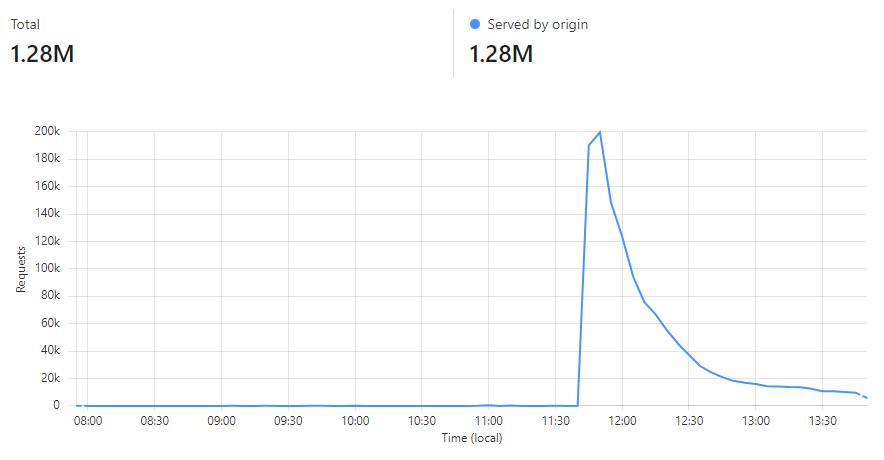

We were reminded of this recently when the FBI reached out and asked if they could send us 630 million more passwords. For the last four years, they've been sending over passwords found during the course of their investigations in the hope that we can help organisations block them from future use. Back then, we were supporting 1.26 billion searches of the service each month. Now, it's... more:

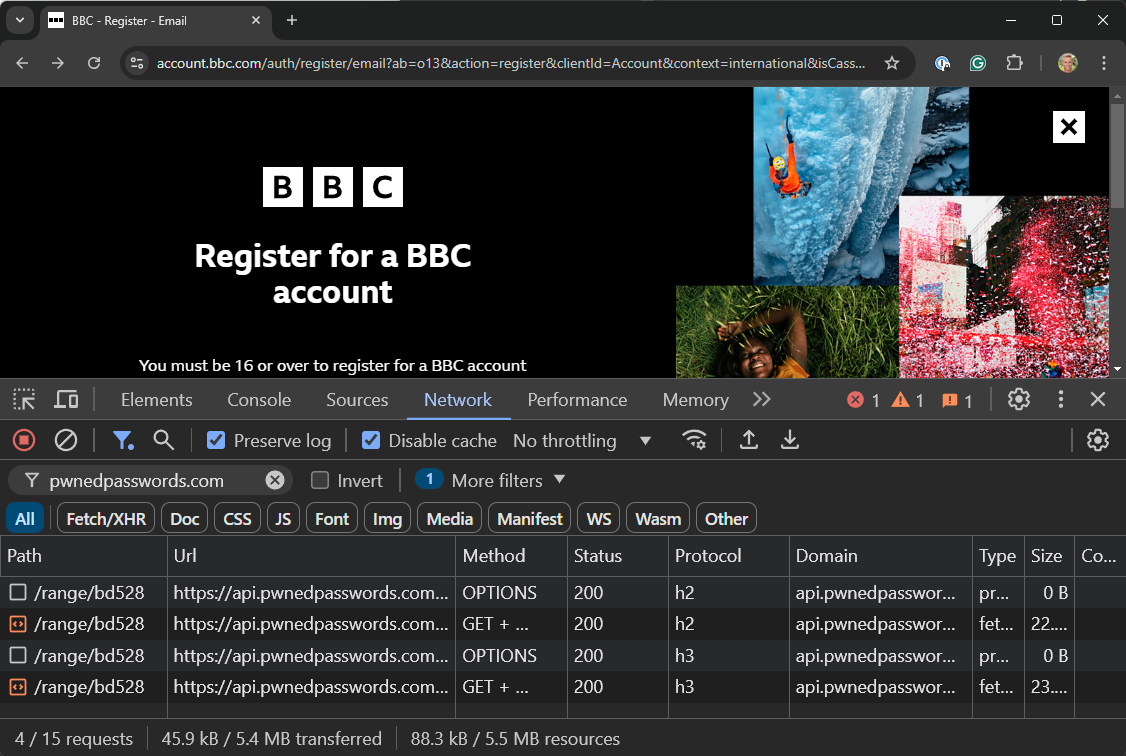

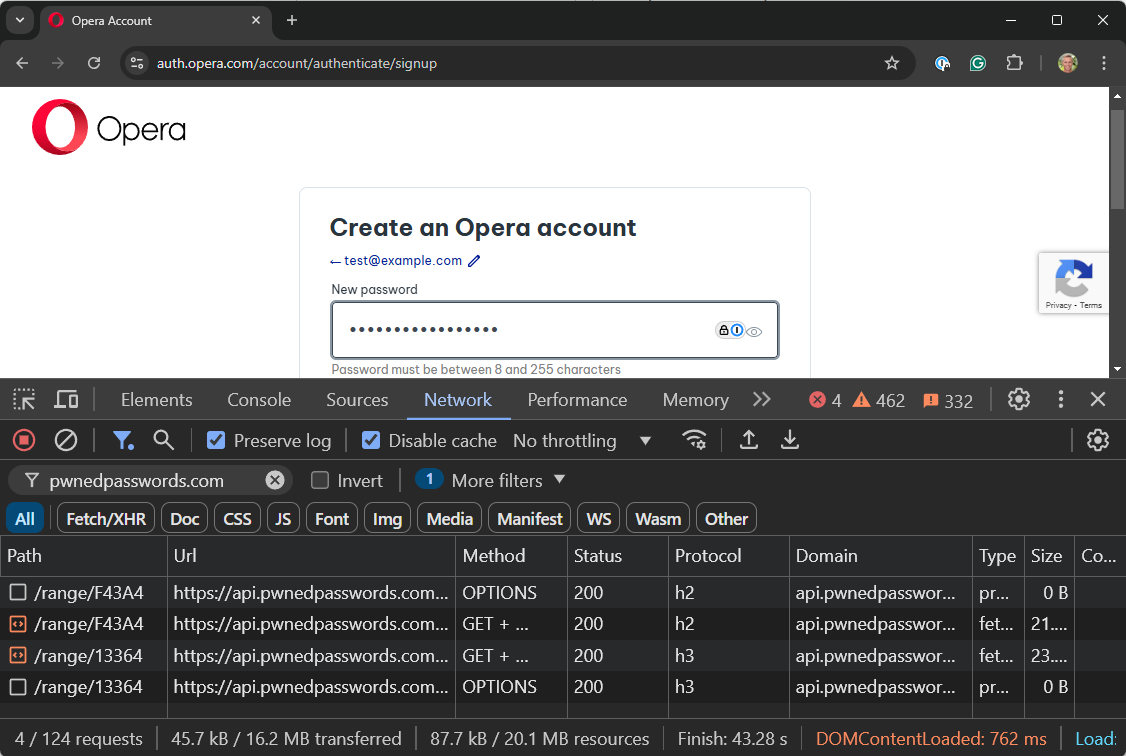

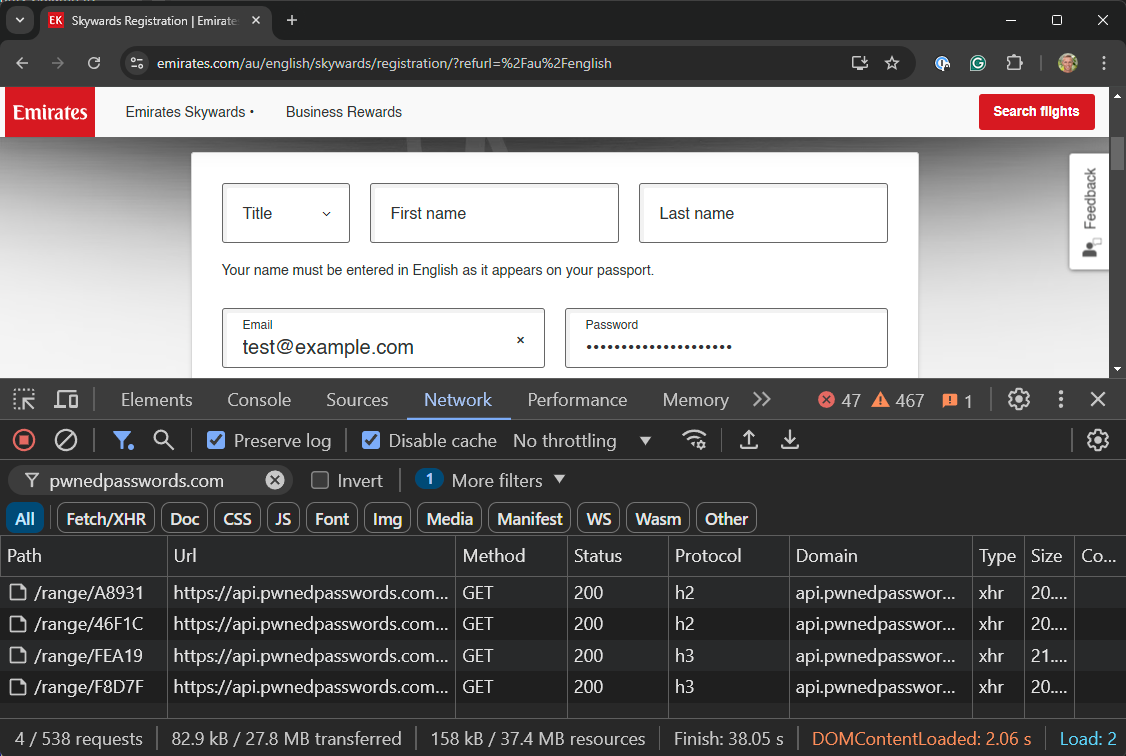

Just as it's hard to wrap your head around the scale of cybercrime, I find it hard to grasp that number fully. On average, that service is hit nearly 7 thousand times per second, and at peak, it's many times more than that. Every one of those requests is a chance to stop an account takeover. But the real scale goes well beyond the API itself. Because the data model is open source and freely available, many organisations use the Pwned Passwords Downloader to take the entire corpus offline and query it directly within their own applications. That tool alone calls the API around a million times during download, but the resulting data is then queried… well, who knows how many times after that. Pretty cool, right?

This latest corpus of data came to us as a result of the FBI seizing multiple devices belonging to a suspect. The data appeared to have originated from both the open web and Tor-based marketplaces, Telegram channels and infostealer malware families. We hadn't seen about 7.4% of them in HIBP before, which might sound small, but that's 46 million vulnerable passwords we weren't giving people using the service the opportunity to block. So, we've added those and bumped the prevalence count on the other 584 million we already had.

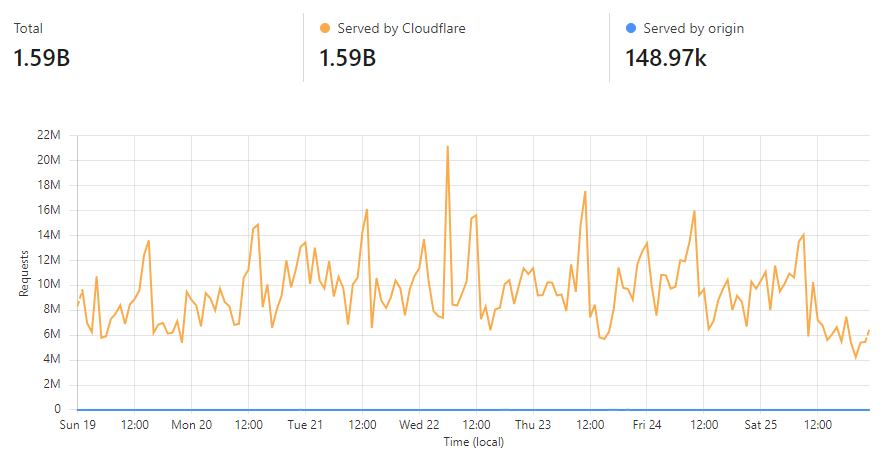

We're thrilled to be able to provide this service to the community for free and want to also quickly thank Cloudflare for their support in providing us with the infrastructure to make this possible. Thanks to their edge caching tech, all those passwords are queryable from a location just a handful of milliseconds away from wherever you are on the globe.

If you're hitting the API, then all the data is already searchable for you. If you're downloading it all offline, go and grab the latest data now. Either way, go forth and put it to good use and help make a cybercriminal's day just that much harder 😊

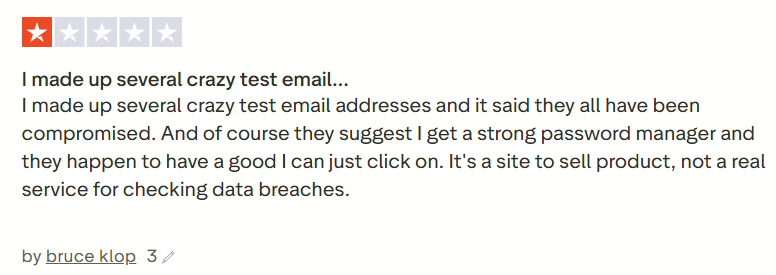

Normally, when someone sends feedback like this, I ignore it, but it happens often enough that it deserves an explainer, because the answer is really, really simple. So simple, in fact, that it should be evident to the likes of Bruce, who decided his misunderstanding deserved a 1-star Trustpilot review yesterday:

Now, frankly, Trustpilot is a pretty questionable source of real-world, quality reviews anyway, but the same feedback has come through other channels enough times that let's just sort this out once and for all. It all begins with one simple question:

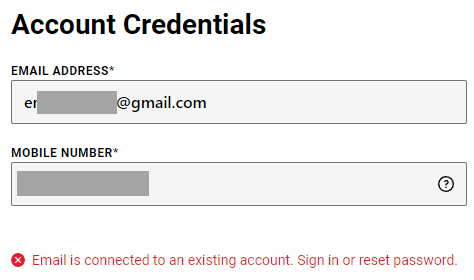

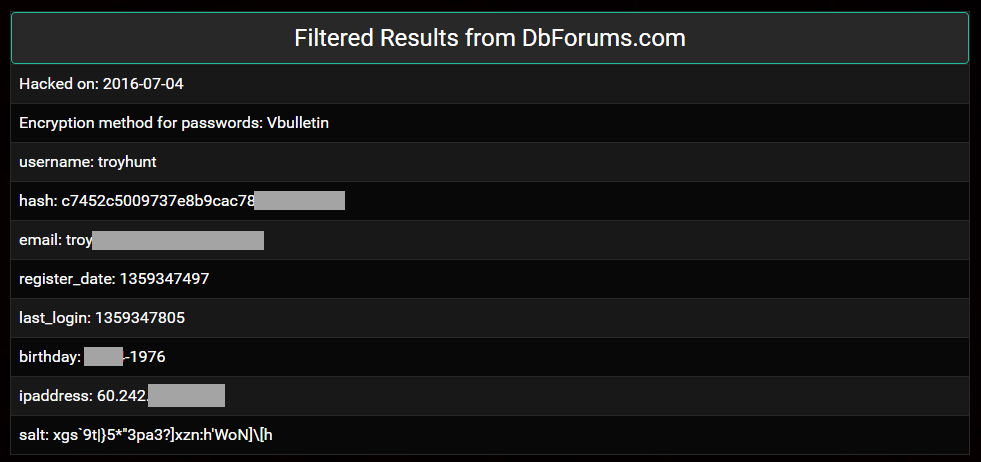

You think you know - and Bruce thinks he knows - but you might both be wrong. To explain the answer to the question, we need to start with how HIBP ingests data, and that really is pretty simple: someone sends us a breach (which is typically just text files of data), and we run the open source Email Address Extractor tool over it, which then dumps all the unique addresses into a file. That file is then uploaded into the system, where the addresses are then searchable.

The logic for how we extract addresses is all in that Github repository, but in simple terms, it boils down to this:

That is all! We can't then tell if there's an actual mailbox behind the address, as that would require massive per-address processing, for example, sending an email to each one and seeing if it bounces. Can you imagine doing that 7 billion times?! That's the number of unique addresses in HIBP, and clearly, it's impossible. So, that means all the following were parsed as being valid and loaded into HIBP (deep links to the search result):

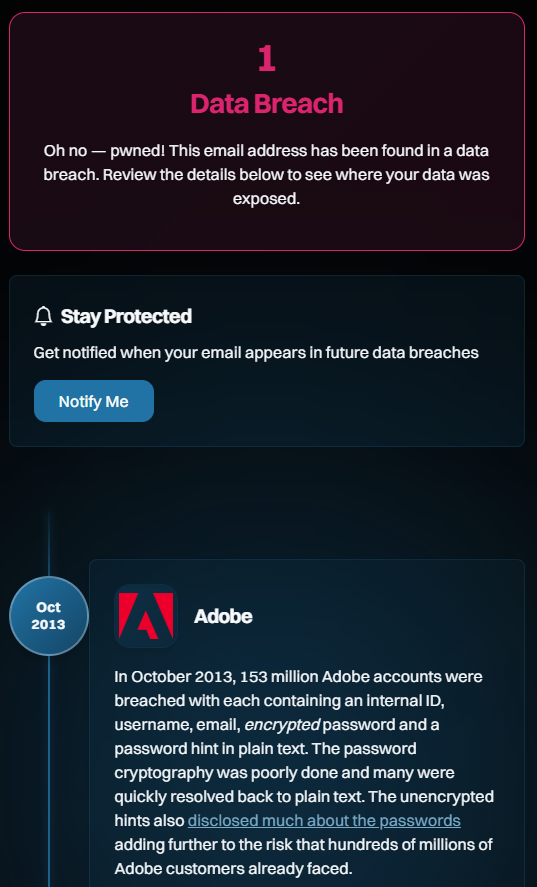

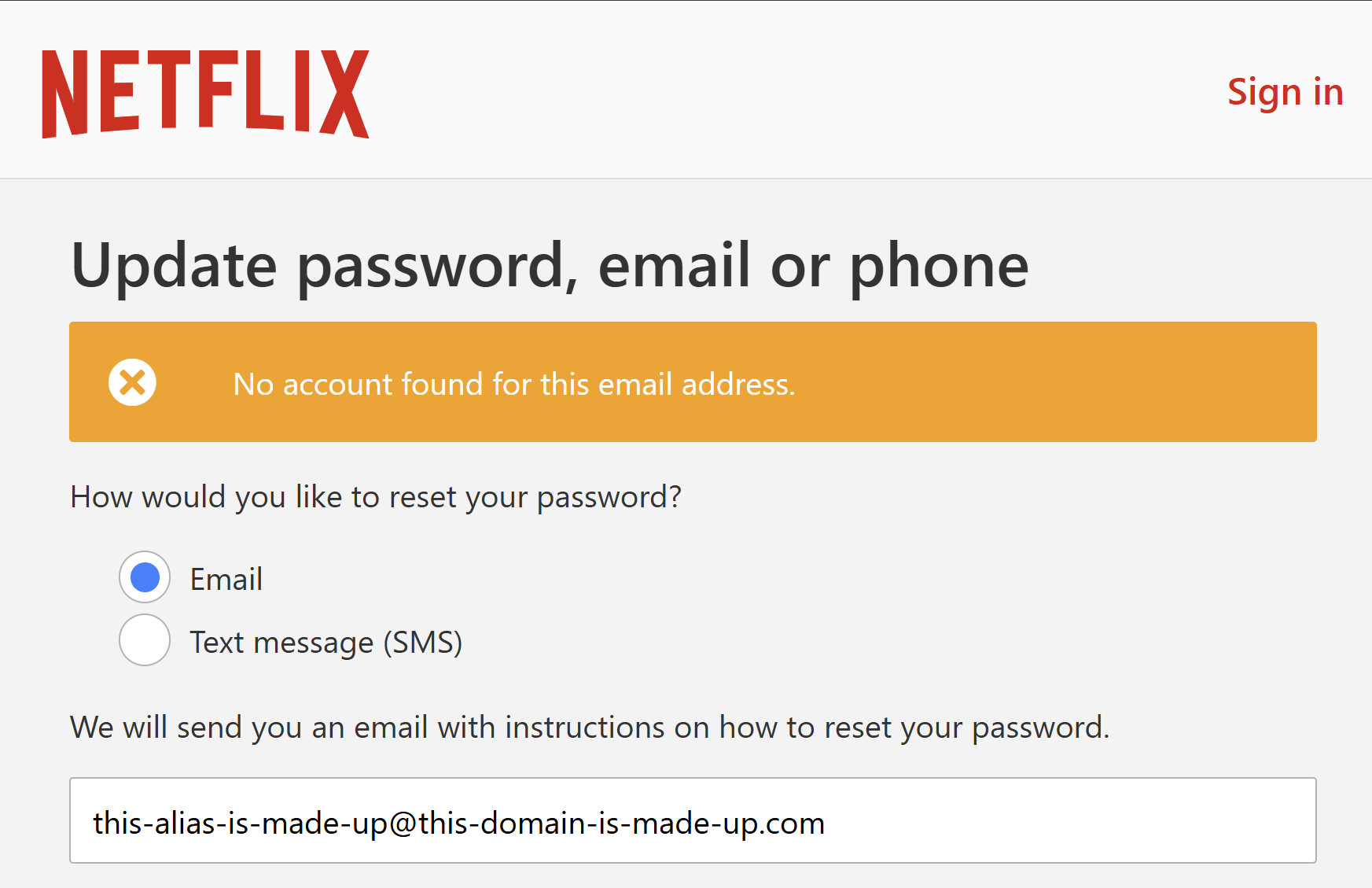

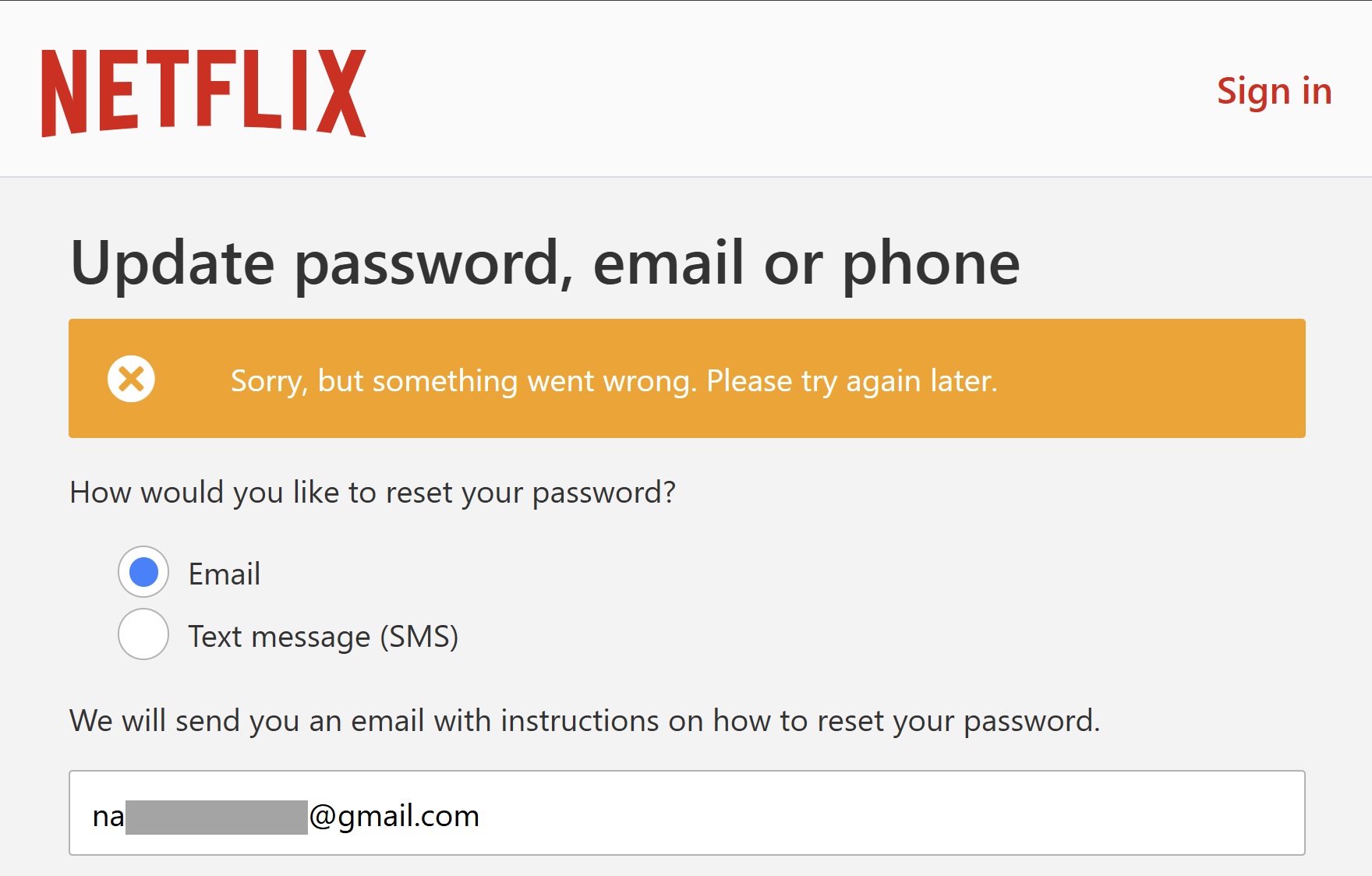

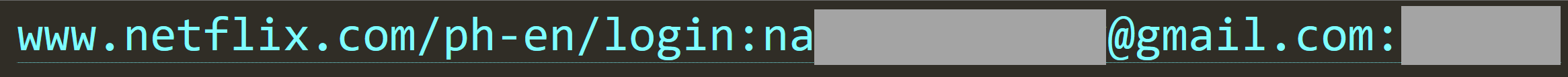

I particularly like that last one, as it feels like a sentiment Bruce would express. It's also a great example as it's clearly not "real"; the alias is a bit of a giveaway, as is the domain ("foo" is commonly used as a placeholder, similar to how we might also use "bar", or combine them as "foo bar"). But if you follow the link and see the breach it was exposed in, you'll see a very familiar name:

Which brings us to the next question:

This is also going to seem profoundly simple when you see it. Here goes:

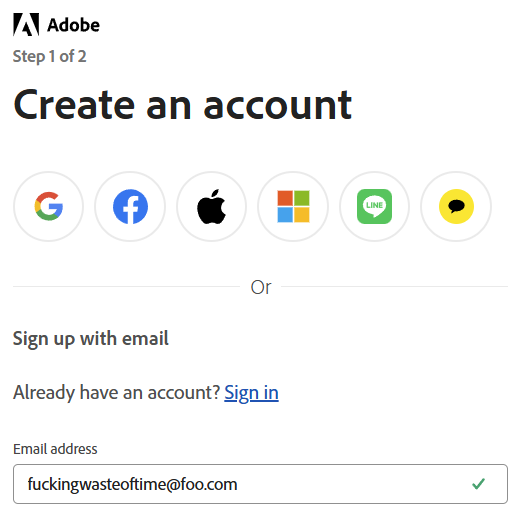

Any questions, Bruce? This is just as easily explainable as why we considered it a valid address and ingested it into HIBP: the email address has a valid structure. That is all. That's how it got into Adobe, and that's how it then flowed through into HIBP.

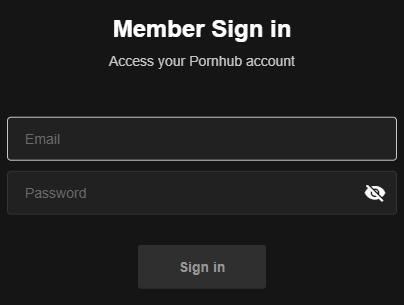

Ah, but shouldn't Adobe verify the address? I mean, shouldn't they send an email to the address along the lines of "Hey, are you sure you want to sign up for this service?" Yes, they should, but here's the kicker: that doesn't stop the email address from being added to their database in the first place! The way this normally works (and this is what we do with HIBP when you sign up for the free notification service) is you enter the email address, the system generates a random token, and then the two are saved together in the database. A link with the token is then emailed to the address and used to verify the user if they then follow that link. And if they don't follow that link? We delete the email address if it hasn't been verified within a few days, but evidently, Adobe doesn't. Most services don't, so here we are.

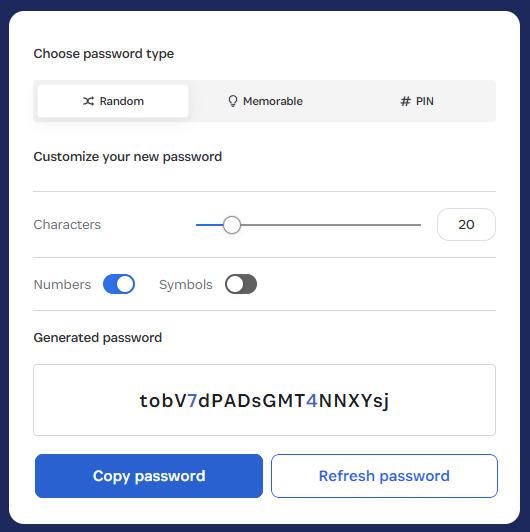

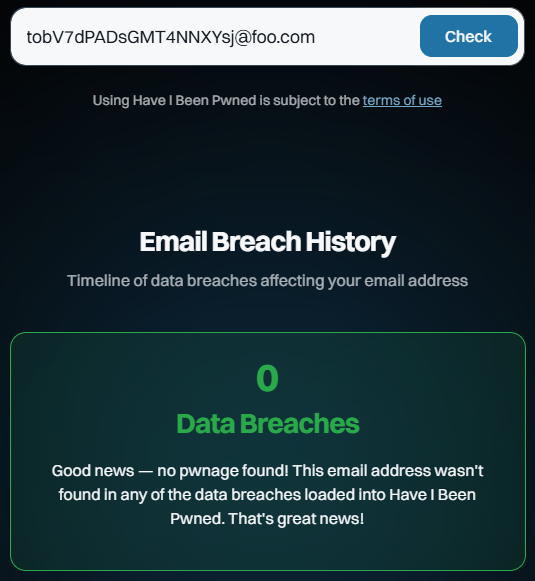

This is also going to seem profoundly obvious, but genuinely random email addresses (not "thisisfuckinguseless@") won't show up in HIBP. Want to test the theory? Try 1Password's generator (yes, Bruce, they also sponsor HIBP):

Now, whack that on the foo.com domain and do a search:

Huh, would you look at that? And you can keep doing that over and over again. You’ll get the same result because they are fabricated addresses that no one else has created or entered into a website that was subsequently breached, ipso facto proving they cannot appear in the dataset.

Today is HIBP's 12th birthday, and I've taken particular issue with Bruce's review because it calls into question the integrity with which I run this service. This is now the 218th blog post I've written about HIBP, and over the last dozen years, I've detailed everything from the architecture to the ethical considerations to how I verify breaches. It's hard to imagine being any more transparent about how this service runs, and per the above, it's very simple to disprove the Bruces of the world. If you've read this far and have an accurate, fact-based review you'd like to leave, that'd be awesome 😊

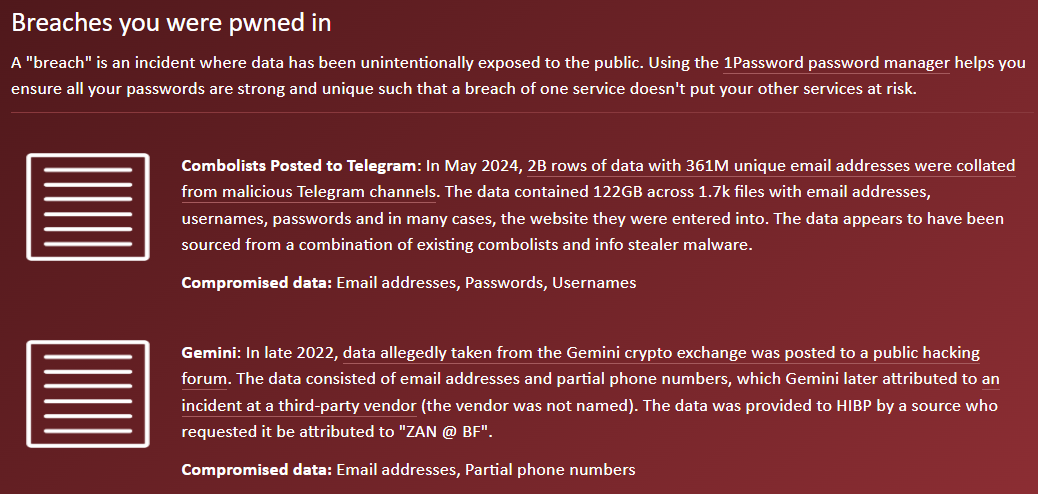

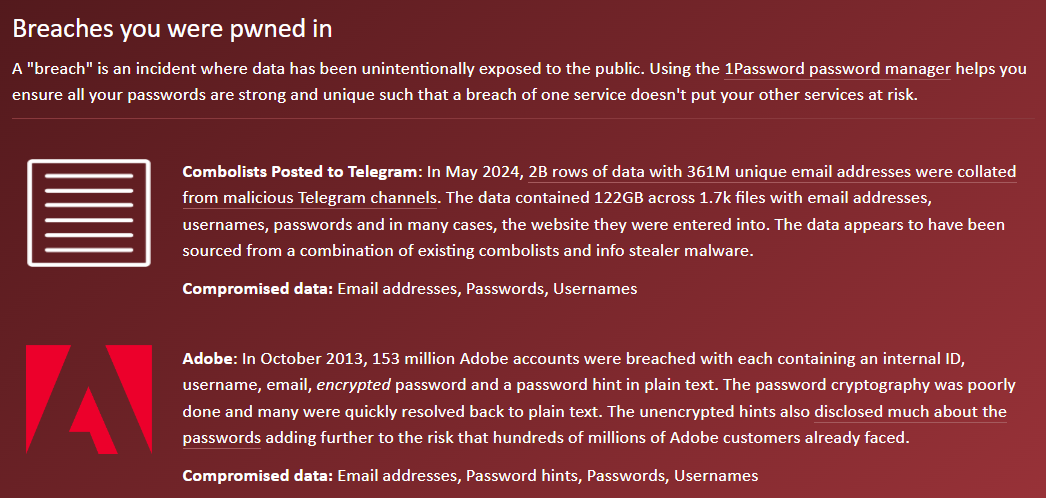

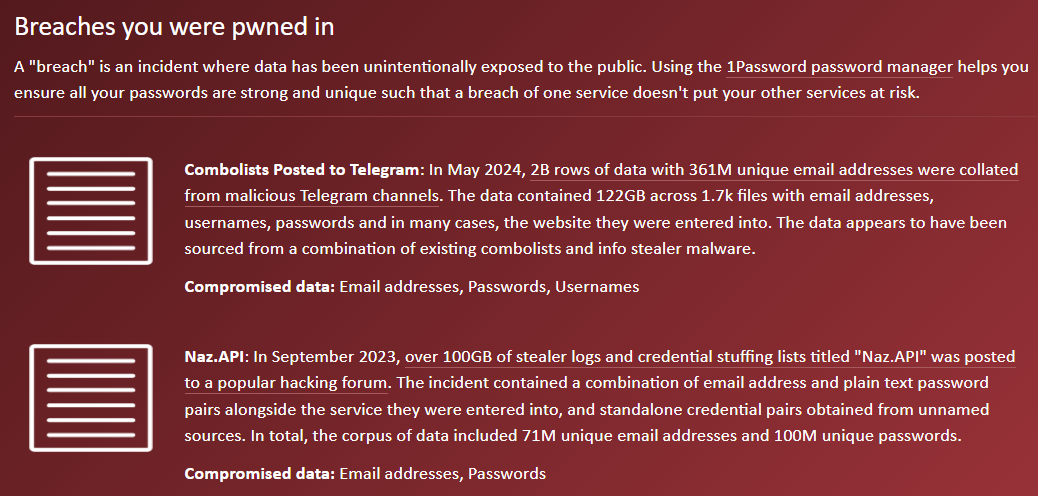

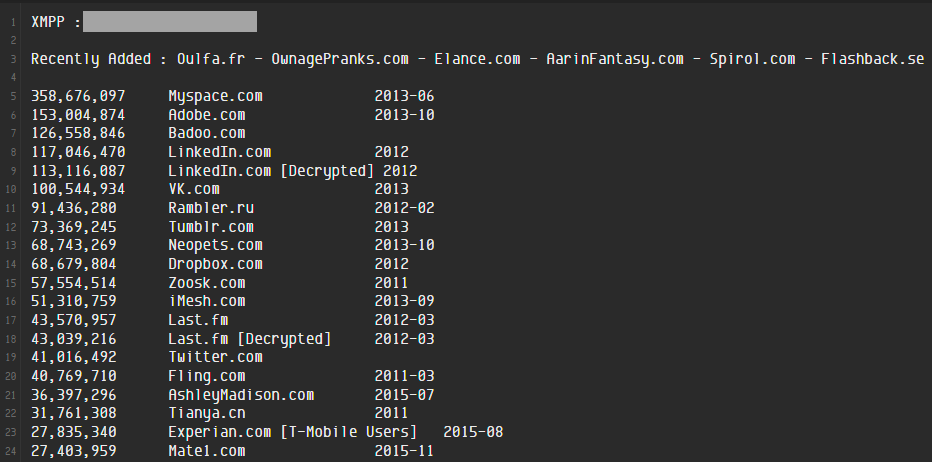

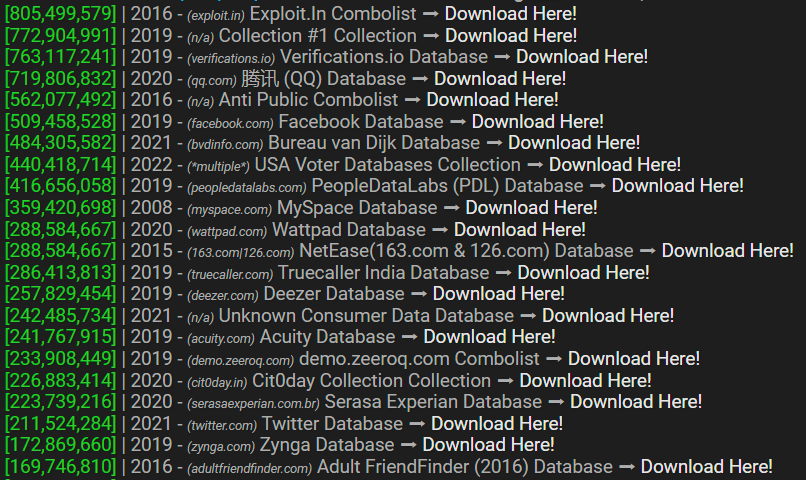

I hate hyperbolic news headlines about data breaches, but for the "2 Billion Email Addresses" headline to be hyperbolic, it'd need to be exaggerated or overstated - and it isn't. It's rounded up from the more precise number of 1,957,476,021 unique email addresses, but other than that, it's exactly what it sounds like. Oh - and 1.3 billion unique passwords, 625 million of which we'd never seen before either. It's the most extensive corpus of data we've ever processed, by a significant margin.

Edit: Just to be crystal clear about the origin of the data and the role of Synthient (who you’ll read about in the next paragraph): this data came from numerous locations where cybercriminals had published it. Synthient (run by Ben during his final year of college) indexed that data and provided it to Have I Been Pwned solely for the purpose of notifying victims. He’s the good guy shining a light on the bad guys, so keep that in mind as you read on. (Some of the feedback Ben has received is exactly what I foreshadowed in the final paragraph of this post.)

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the 183M unique email addresses that Synthient had indexed in their threat intelligence platform and then shared with us. I explained that this was only part of the corpus of data they'd indexed, and that it didn't include the credential stuffing records. Stealer log data is obtained by malware running on infected machines. In contrast, credential stuffing lists usually originate from other data breaches where email addresses and passwords are exposed. They're then bundled up, sold, redistributed, and ultimately used to log in to victims' accounts. Not just the accounts they were initially breached from, either, because people reuse the same password over and over again, the data from one breach is frequently usable on completely unrelated sites. A breach of a forum to comment on cats often exposes data that can then be used to log in to the victim's shopping, social media and even email accounts. In that regard, credential stuffing data becomes "the keys to the castle".

Let me run through how we verified the data, what you can do about it and for the tech folks, some of the hoops we had to jump through to make processing this volume of data possible.

The first person whose data I verified was easy - me 😔 An old email address I've had since the 90s has been in credential stuffing lists before, so it wasn't too much of a surprise. Furthermore, I found a password associated with my address, which I'd definitely used many eons ago, and it was about as terrible as you'd expect from that era. However, none of the other passwords associated with my address were familiar. They certainly looked like passwords that other people might have feasibly used, but I'm pretty sure they weren't mine. One was even just an IP address from Perth on the other side of the country, which is both infeasible as a password I would have used, yet eerily close to home. I mean, of all the places in the world an IP address could have appeared from, it had to be somewhere in my own country I've been many times before...

Moving on to HIBP subscribers, I reached out to a handful and asked for support verifying the data. I chose a mix of subscribers with many who'd never been involved in any data breach we'd ever seen before; my experience above suggested that there's recycled data in there, and we had previously verified that when investigating those other incidents. However, is the all-new stuff legitimate? The very first response I received was exactly what I was looking for:

#1 is an old password that I don't use anymore. #2 is a more recent password. Thanks for the heads up, I've gone and changed the password for every critical account that used either one.

Perfectly illustrating most people's behaviour with passwords, #2 referred to above was just #1 with two exclamation marks at the end!! (Incidentally, these were simple six and eight-character passwords, and neither of them was in Pwned Passwords either.) He had three passwords in total, which also means one of them, like with my data, was not familiar. However, the most important thing here is that this example perfectly illustrates why we put the effort into processing data like this: #2 was a real, live password that this guy was actively using, and it was sitting right next to his email address, being passed around among criminals. However, through this effort, that credential pair has now become useless, which is precisely what we're aiming for with this exercise, just a couple of billion times over.

The second respondent only had one password against their address:

Yes that was a password I used for many years for what I would call throw away or unimportant accounts between 20 and 10 years ago

That was also only eight characters, but this time, we'd seen it in Pwned Passwords many times before. And the observation about the password's age was consistent with my own records, so there's definitely some pretty old data in there.

The following response was not at all surprising:

I am familiar with that password... I used it almost 10 years ago... and cannot recall the last time I used it.

That was on a corporate account, too, and the owner of the address duly forwarded my email to the cybersecurity team for further investigation. The single password associated with this lady's email address had a massive nine characters, and also hadn't previously appeared in Pwned Passwords.

Next up was a respondent who replied inline to my questions, so I'll list them below with the corresponding answers:

Is this familiar? Yes

Have you ever used it in the past? Yes and is still on some accounts I do not use any longer.

And if so, how long ago? Unfortunately, it is still on some active accounts that I have just made a list of to change or close immediately.

This individual's eight-character password with uppercase, lowercase, numbers and a "special" character also wasn't in Pwned Passwords. Similarly, as with the earlier response, that password was still in active use, posing a real risk to the owner. It would pass most password complexity criteria and slip through any service using Pwned Passwords to block bad ones, so again, this highlights why it was so important for us to process the data.

The next person had three different passwords against rows with their email address, and they came back with a now common response:

Yes, these are familiar, last used 10 years ago

We'd actually seen all three of them in Pwned Passwords before, many times each. Another respondent with precisely the kind of gamer-like passwords you'd expect a kid to use (one of which we hadn't seen before), also confirmed (I think?) their use:

maybe when i was a kid lol

Responses that weren't an emphatic "yes, that's my data" were scarce. The two passwords against one person's name were both in Pwned Passwords (albeit only once each), yet it's entirely possible that neither of them had been used by this specific individual before. It's also possible they'd forgotten a password they'd used more than a decade ago, or it may have even been automatically assigned to them by the service that was subsequently breached. Put it down as a statistical anomaly, but I thought it was worth mentioning to highlight that being in this data set isn't a guarantee of a genuine password of yours being exposed. If your email address is found in this corpus then that's real, of course, so there must be some truth in the data, but it's a reminder that when data is aggregated from so many different sources over such a long period of time, there's going to be some inconsistencies.

As a brief recap, we load passwords into the service we call Pwned Passwords. When we do so, there is absolutely no association between the password and the email address it appeared next to. This is for both your protection and ours; can you imagine if HIBP was pwned? It's not beyond the realm of possibility, and the impact of exposing billions of credential pairs that can immediately unlock an untold number of accounts would be catastrophic. It's highly risky, and completely unnecessary when you can search for standalone passwords anyway without creating the risk of it being linked back to someone.

Think about it: if you have a password of "Fido123!" and you find it's been previously exposed (which it has), it doesn't matter if it was exposed against your email address or someone else's; it's still a bad password because it's named after your dog followed by a very predictable pattern. If you have a genuinely strong password and it's in Pwned Passwords, then you can walk away with some confidence that it really was yours. Either way, you shouldn't ever use that password again anywhere, and Pwned Passwords has done its job.

Checking the service is easy, anonymous and depending on your level of technical comfort, can be done in several different ways. Here's a copy and paste from the last Synthient blog post:

My vested interest in 1Password aside, Watchtower is the easiest, fastest way to understand your potential exposure in this incident. And in case you're wondering why I have so many vulnerable and reused passwords, it's a combination of the test accounts I've saved over the years and the 4-digit PINs some services force you to use. Would you believe that every single 4-digit number ever has been pwned?! (If you're interested, the ABC has a fantastic infographic using a heatmap based on HIBP data that shows some very predictable patterns for 4-digit PINs.)

It pains me to say it, but I have to, given the way the stealer logs made ridiculous, completely false headlines a couple of weeks ago:

This story has suddenly gained *way* more traction in recent hours, and something I thought was obvious needs clarifying: this *is not* a Gmail leak, it simply has the credentials of victims infected with malware, and Gmail is the dominant email provider: https://t.co/S75hF4T1es

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) October 27, 2025

There are 32 million different email domains in this latest corpus, of which gmail.com is one. It is, of course, the largest and has 394 million unique email addresses on it. In other words, 80% of the data in this corpus has absolutely nothing to do with Gmail, and the 20% of Gmail addresses have absolutely nothing to do with any sort of security vulnerability on Google's behalf. There - now let reporting sanity prevail!

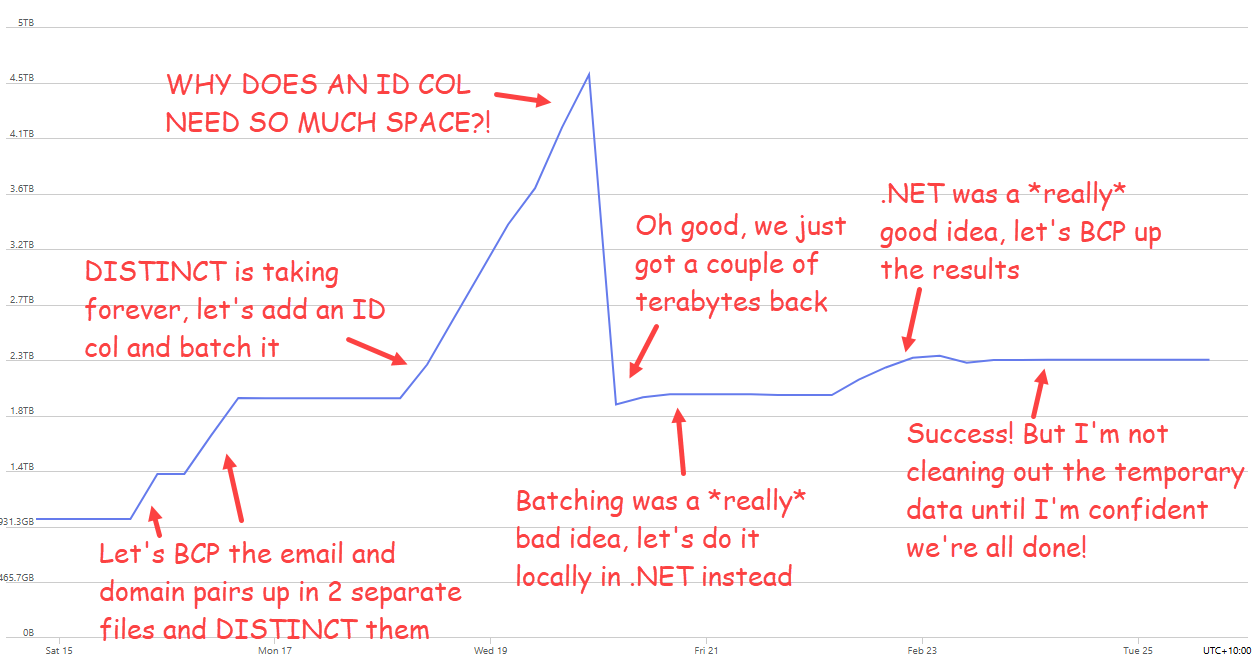

I wanted to add this just to highlight how painful it has been to deal with this data. This corpus is nearly 3 times the size of the previous largest breach we'd loaded, and HIBP is many times larger than it was in 2019 when we loaded the Collection #1 data. Taking 2 billion records and adding the ones we hadn't already seen in the existing 15 billion corpus, whilst not adversely impacting the live system serving millions of visitors a day, was very non-trivial. Managing the nuances of SQL Server indexes such that we could optimise both inserts and queries is not my idea of fun, and it's been a pretty hard couple of weeks if I'm honest. It's also been a very expensive period as we turned the cloud up to 11 (we run on Azure SQL Hyperscale, which we maxed out at 80 cores for almost two weeks).

A simple example of the challenge is that after loading all the email addresses up into a staging table, we needed to create SHA1 hashes of each. Normally, that would involve something to the effect of "update table set column = sha1(email)" and you're done. That crashed completely, so we ended up doing "insert into new table select email, sha1(email)". But on other occasions the breach load required us to do updates on other columns (with no hash creation), which, on mulitple occasions, we had to kill after a day or more of execution with no end in sight. So, we ended up batching in loops (usually 1M records at a time), reporting on progress along the way so we had some idea of when it would actually finish. It was a painful process of trial, waiting ages, error then taking a completely different approach.

Notifying our subscribers is another problem. We have 5.9 million of them, and 2.9 million are in this data 🫨 Simply sending that many emails at once is hard. It's not so much hard in terms of firing them off, rather it's hard in terms of not ending up on a reputation naughty list or having mail throttled by the receiving server. That's happened many times in the past when loading large, albeit much smaller corpuses; Gmail, for example, suddenly sees a massive spike and slows down the delivery to inboxes. Not such a biggy for sending breach notices, but a major problem for people trying to sign into their dashboard who can no longer receive the email with the "magic" link.

What we've done to address that for this incident is to slow down the delivery of emails for the individual breach notification. Whilst I'd originally intended to send the emails at a constant rate over the period of a week, someone listening to me on my Friday live stream had a much better suggestion:

the strategy I've found to best work with large email delivery is to look at the average number of emails you've sent over the last 30 days each time you want to ramp up, and then increase that volume by around 50% per day until you've worked your way through the queue

Which makes a lot of sense, and stacked up as I did more research (thanks Joe!). So, here's what our planned delivery schedule now looks like:

That's broken down by hour, increasing in volume by 1.015 times per hour, such that the emails are spread out in a similar, gradually increasing cadence. On a daily basis, that works out at a 45% increase in each 24-hour period, within Joe's suggested 50% threshold. Plus, we obviously have all the other mechanisms such as a dedicated IP, properly configured DKIM, DMARC and SPF, only emailing double-opted-in subscribers and spam-friendly message body construction. So, it could be days before you receive a notification, or just run a haveibeenpwned.com search on demand if you're impatient.

We've sent all the domain notification emails instantly because, by definition, they're going to a very wide range of different mail servers; it's just the individual ones we're drop-feeding.

Lastly, if you've integrated Pwned Passwords into your service, you'll now see noticeably larger response sizes. The numbers I mentioned in the opening paragraph increase the size of each hash range by an average of about 50%, which will push responses from about 26kb to 40kb. That's when brotli compressed, so obviously, make sure you're making requests that make the most of the compression.

This data is now searchable in HIBP as the Synthient Credential Stuffing Threat Data. It's an entirely separate corpus from that previous Synthient data I mentioned earlier; they're discrete datasets with some crossover, but obviously, this one is significantly larger. And, of course, all the passwords are now searchable per the Pwned Passwords guidance above.

If I could close with one request: this was an extremely laborious, time-consuming and expensive exercise for us to complete. We've done our best to verify the integrity of the data and make it searchable in a practical way while remaining as privacy-centric as possible. Sending as many notifications as we have will inevitably lead to a barrage of responses from people wanting access to complete rows of data, grilling us on precisely where it was obtained from or, believe it or not, outright abusing us. Not doing those things would be awesome, and I suggest instead putting the energy into getting a password manager, making passwords strong and unique (or even better, using passkeys where available), and turning on multi-factor auth. That would be an awesome outcome for all 😊

Edit: I've closed off comments on this blog post. As you'll see below, there was a constant stream of questions that have already been answered in the post itself, plus some comments that were starting to verge on precisely what I predicted in the last para above. Reading, responding and engaging is time-consuming and at this point, all the answers are already here both above and below this edit in the comments.

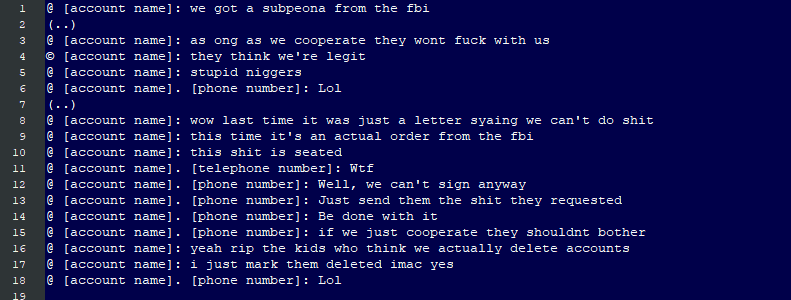

Where is your data on the internet? I mean, outside the places you've consciously provided it, where has it now flowed to and is being used and abused in ways you've never expected? The truth is that once the bad guys have your data, it often replicates over and over again via numerous channels and platforms. If you're able to aggregate enough of it en masse, you end up with huge volumes of "threat intelligence data", to use the industry buzzword. And that's precisely what Ben from Synthient has done, and then sent it to Have I Been Pwned (HIBP).

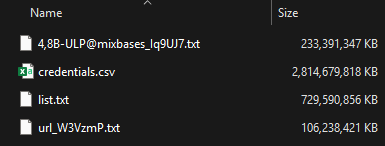

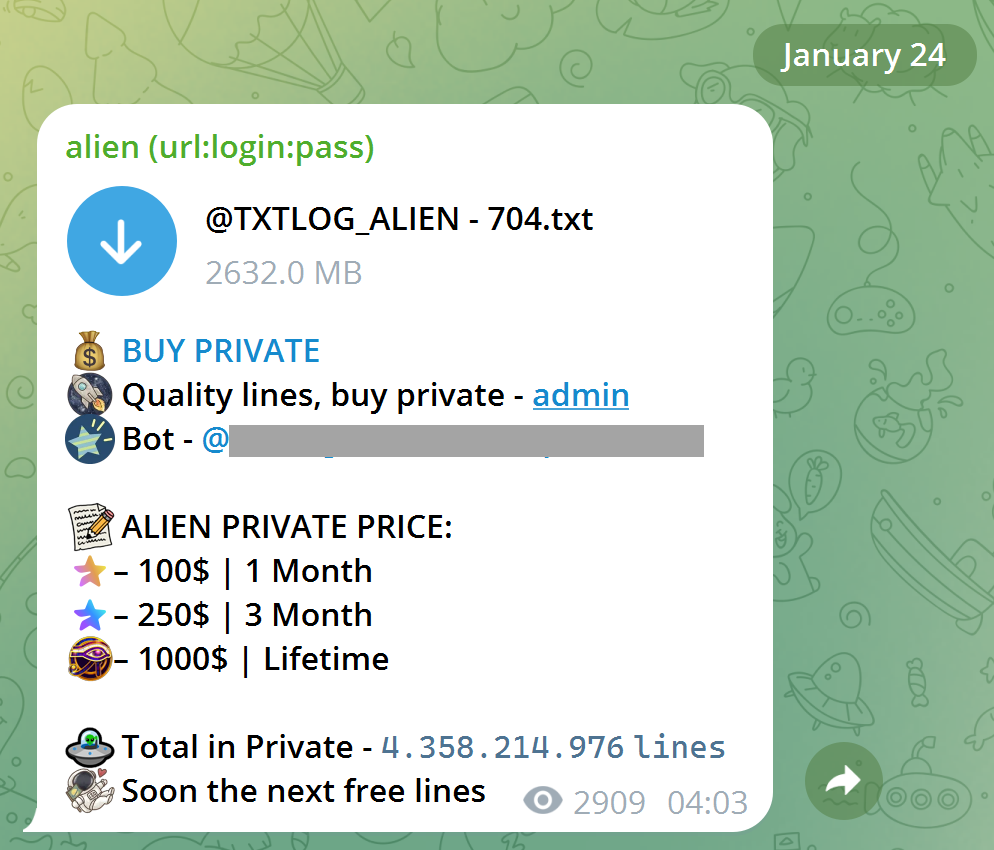

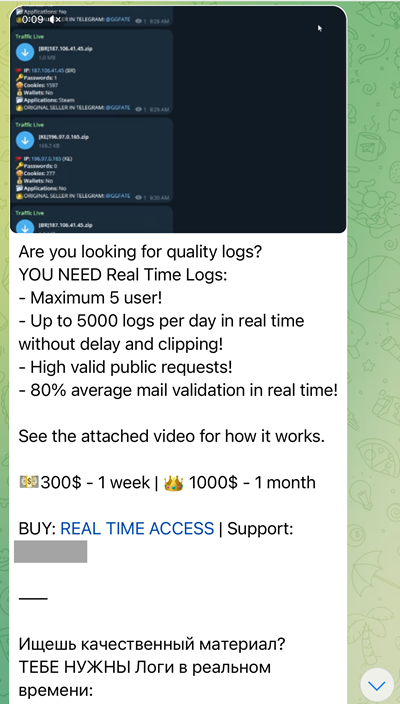

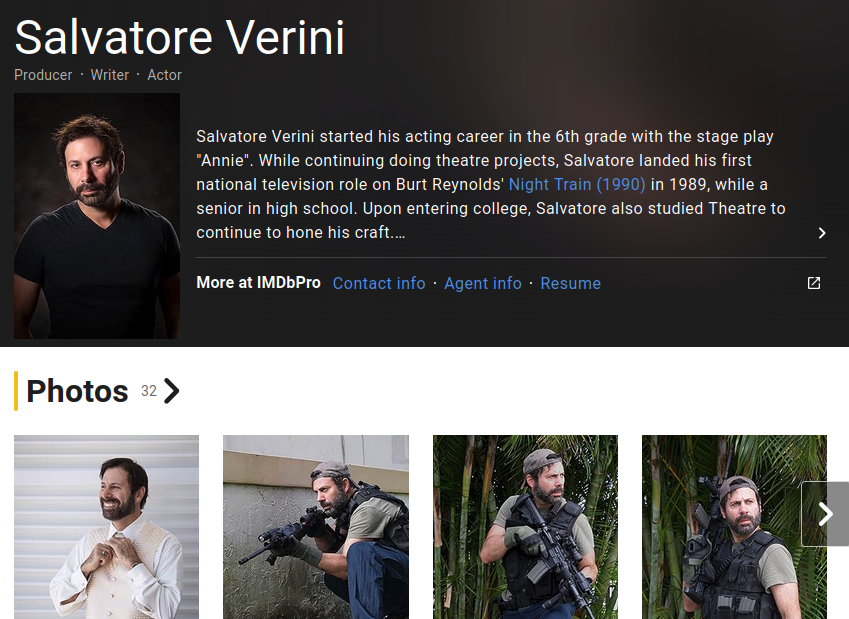

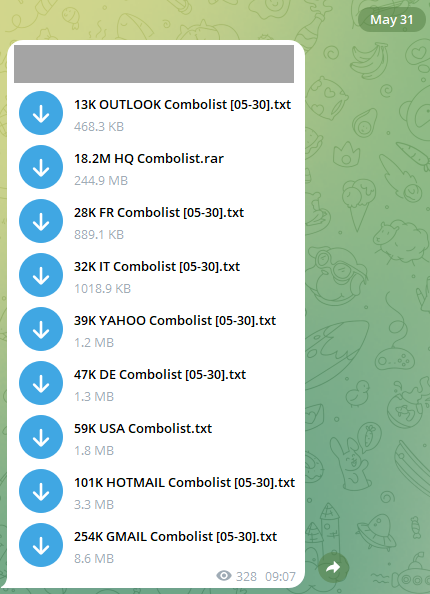

Ben is in his final year of college in the US and is carving out a niche in threat intelligence. He's written up a deeper dive in The Stealer Log Ecosystem: Processing Millions of Credentials a Day, but the headline gives you a sense of the volumes. Have a read of that post and you'll see Ben is pulling data from various sources, including social media, forums, Tor and, of course, Telegram. He's managed to aggregate so much of it that by the time he sent it to us, it was rather sizeable:

That's 3.5 terrabytes of data, with the largest file alone being 2.6TB and, combined, they contain 23 billion rows. It's a vast corpus, and if we were attempting to compete with recent hyperbolic headlines about breach sizes, this would be one of the largest. But I'm not going to play the "mine is bigger than yours" game because it makes no sense once you start analysing the data. Part of what makes the data so large is that we're actually looking at both stealer logs and credential stuffing lists, so let's assess them separately, starting with those stealer logs.

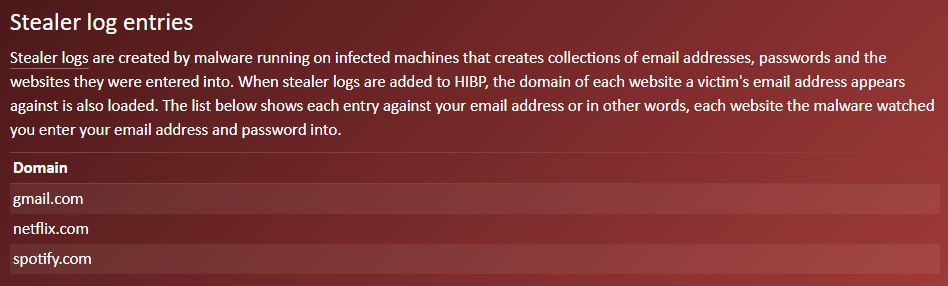

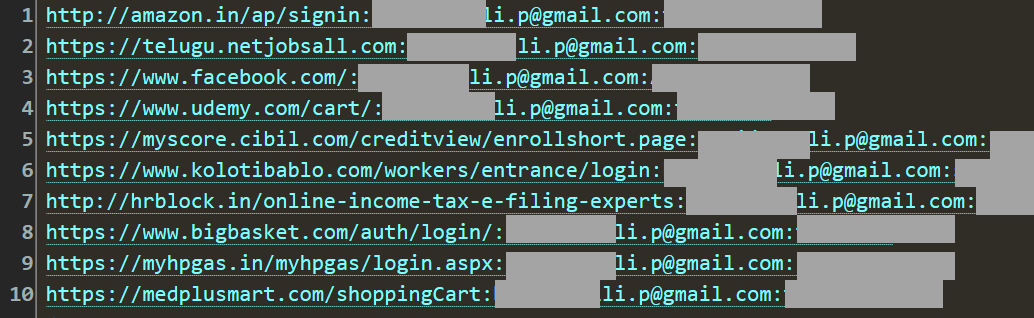

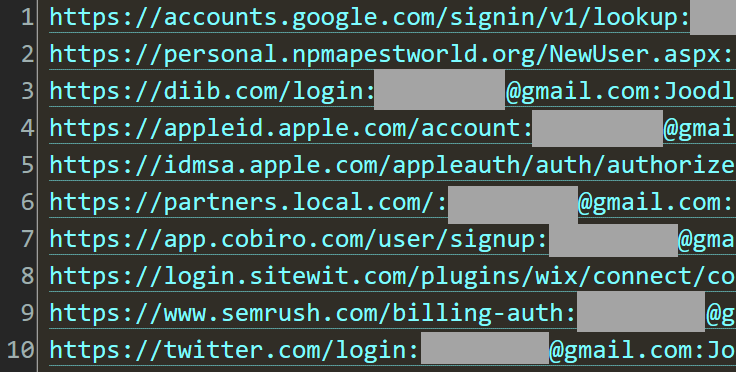

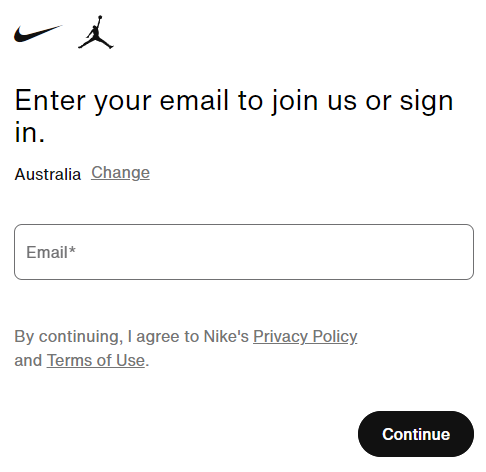

Stealer logs are the product of infostealers, that is, malware running on infected machines and capturing credentials entered into websites on input. The output of those stealer logs is primarily three things:

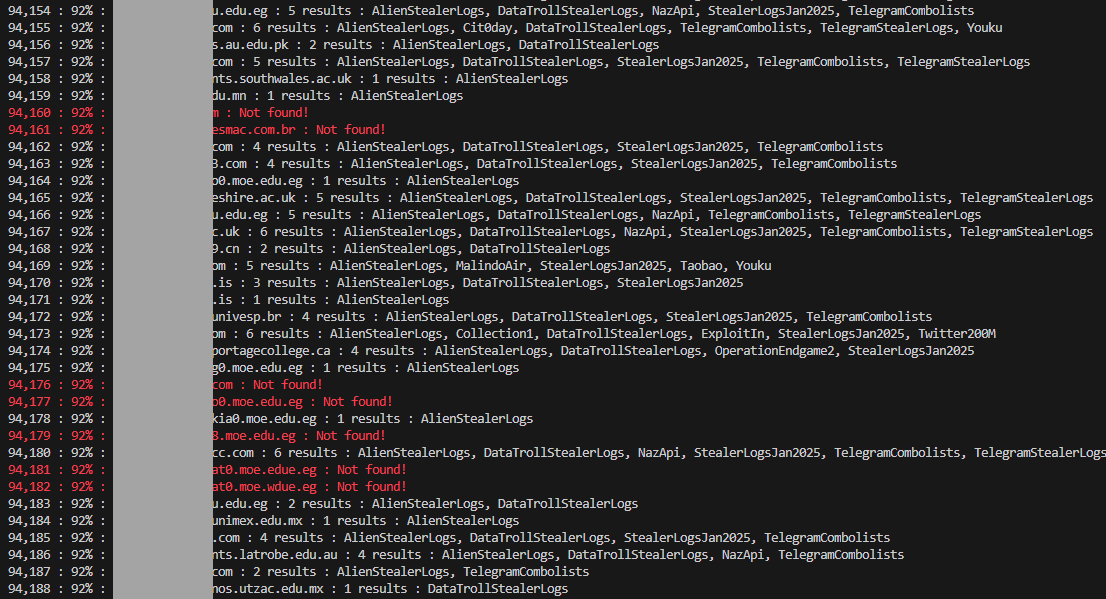

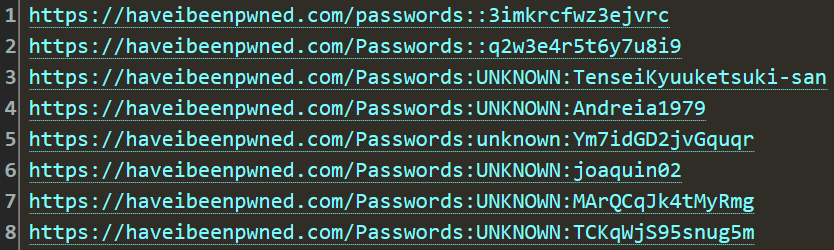

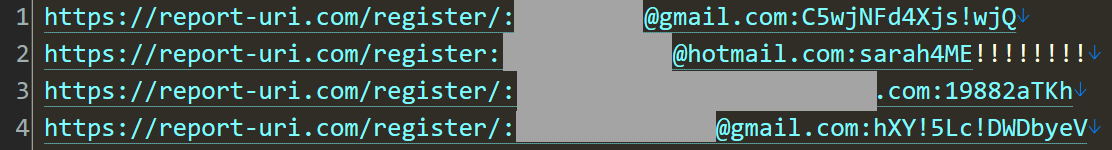

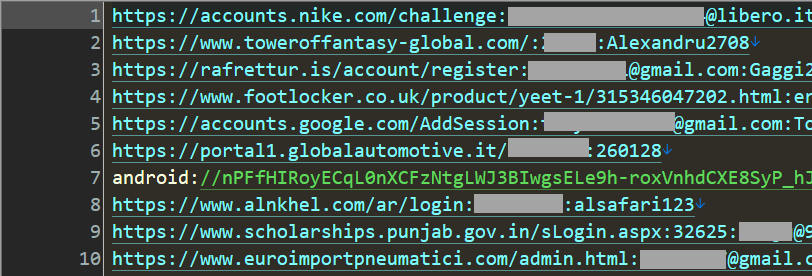

Someone logging into Gmail, for example, ends up with their email address and password captured against gmail.com, hence the three parts. Due to the fact that stealer logs are so heavily recycled (they're posted over and over again to the sorts of channels Ben monitors), the first thing we always do is try to get a sense of how much is genuinely new:

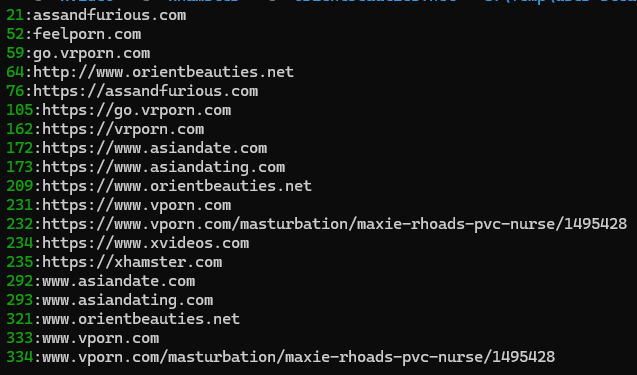

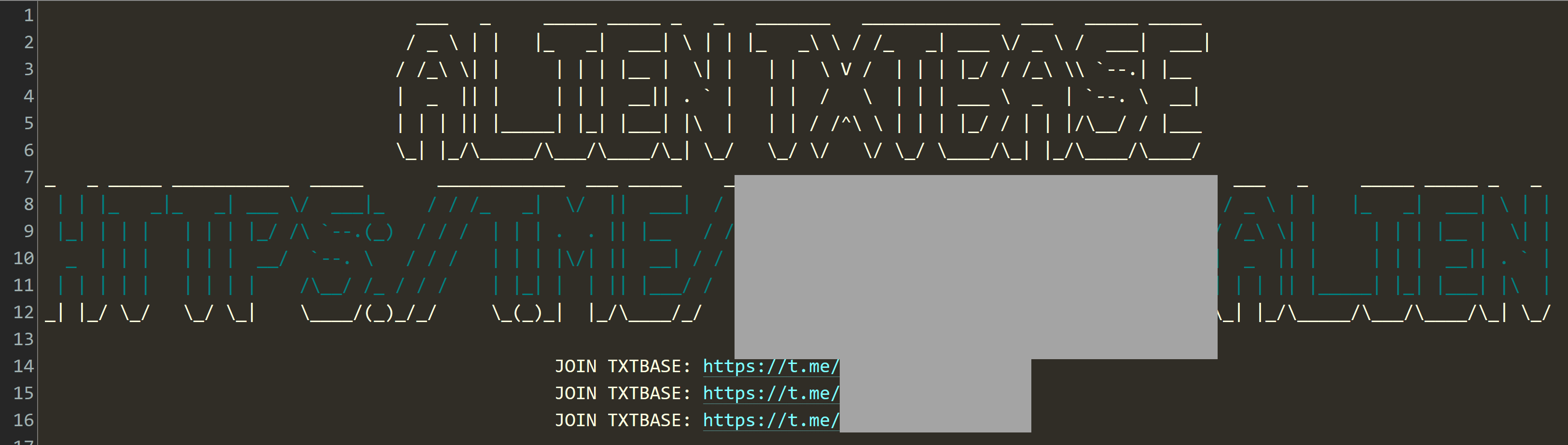

This is the output of a little PowerShell script we use to guage where the email addresses in a new breach corpus have been seen before. Especially when there's a suspicion that data might have been repurposed from elsewhere, it's really useful to run them against the HIBP API and see what comes back. What the output above tells us is that after checking a sample of 94k of them, 92% had been previously seen, mostly in stealer log corpuses we'd loaded in the past. This is an empirical demonstration of what I wrote in the opening paragraph - "it often replicates over and over again" - and as you can see, most of what has been seen before was in the ALIEN TXTBASE stealer logs.

Back to the console output again, and having previously seen 92% of addresses also means we haven't seen 8% of the addresses. That's 8% of a considerable number, too: we found 183M unique email addresses across Ben's stealer log data, so we're talking about 14M+ addresses that have never surfaced in HIBP. (The final number once the entire data set was loaded into HIBP was 91% pre-existing, with 16.4M previously unseen addresses in any data breach, not just stealer logs.) But as with everything we load, the question has to be asked: Is it legit? Can you trust the shady criminals who publish this data not to fill it with junk? The only way to know for sure is to ask the legitimate owners of the data, so I reached out to a bunch of our subscribers and sought their support in verifying.

One of the respondants was already concerned there could be something wrong with his Gmail account and sure enough, he had one stealer log entry for "https://accounts.google.com/signin/challenge/pwd/1" with a, uh, "suboptimal" password:

Yes I can confirm that was an accurate password on my gmail account a few months ago

Another respondant who offered support had somewhat of a recognisable pattern in the sites he'd been visiting:

To his credit, he responded and confirmed that the list did indeed contain sites he'd visited, which also included online casinos, crypto websites and VPN services:

They all look like websites I have used and some still do use

As it turns out, he also had two other email addresses in the corpus of data, both with the same collection of passwords used on the first address he replied from. They also both aligned to services based on the same TLD as the other email address which suggested which country he's located in. (Incidentally, the online privacy offered by VPNs kinda falls apart when there's malware on your machine watching every site you visit and recording your credentials.)

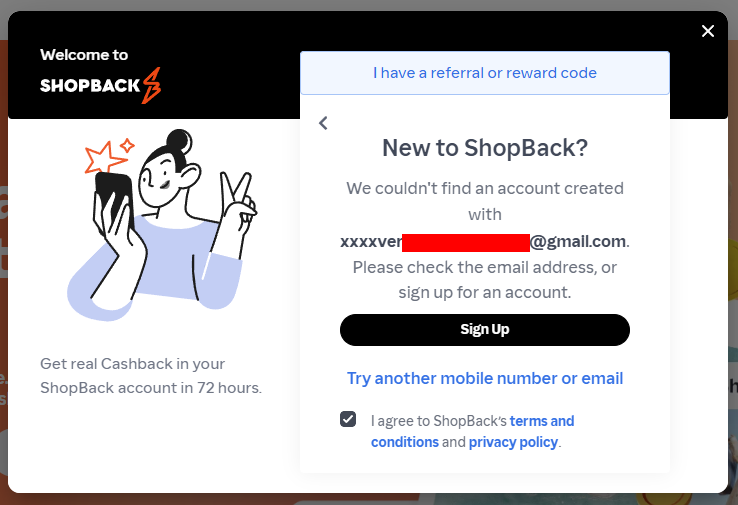

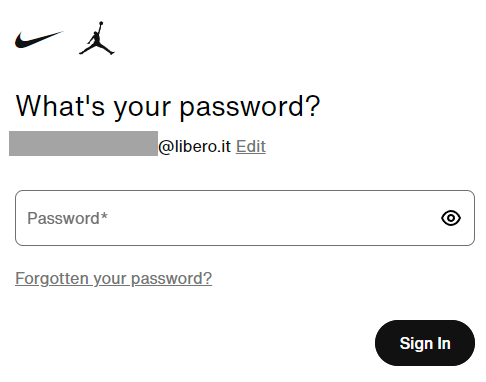

Even without a response from a subscriber, it's still easy to get a sense of the legitimacy of the data in a privacy-preserving fashion (i.e. not logging in with their credentials!) just by testing enumeration vectors. For example, one subscriber had an account at ShopBack in the Philippines which offers what I'll refer to as "account enumeration as a service":

I simply added some character's in front of the email address and ShopBack happily confirmed that address didn't exist. However, remove the invalid characters and there's a very different response:

All of these little "tells" add up; another subscriber had a high prevalence of Greek websites they used, showing exactly the sort of pattern you'd expect to see for someone from that corner of the world. Another had various online survey sites they'd used, and like our "assandfurious" friend from earlier, a clear pattern emerged consistent with the apparent interests of the address's owner. Time and time again, the data checked out, so we loaded it. Those 183M email addresses are now searchable in HIBP, and the passwords are also searchable in Pwned Passwords, which has become rather popular:

Pwned Passwords just served 17.45 billion requests in 30 days 🤯 That's an *average* of 6,733 requests per second, but at our peak, we're hitting 42k per second in a 1-minute block. Crazy numbers! Made possible by @Cloudflare 😎 pic.twitter.com/Io6u1PiqJf

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) October 17, 2025

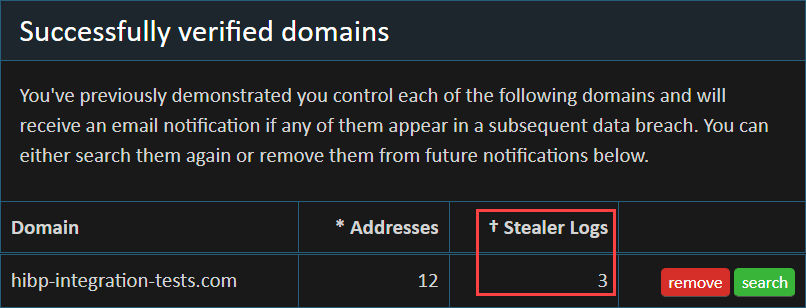

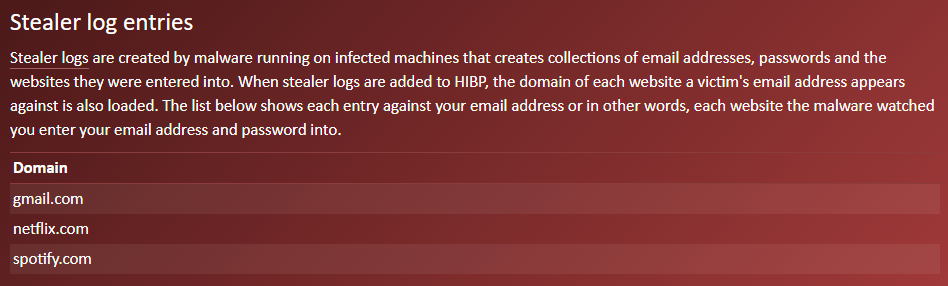

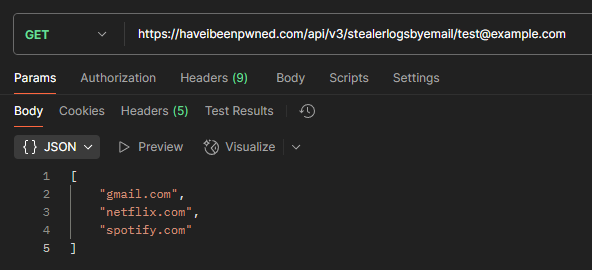

The website addresses are also now searchable, either in the stealer log section of your personal dashboard or by verified domain owners using the API. You'll find this data named "Synthient Stealer Log Threat Data" in HIBP, but stealer logs are only part of the Synthient story - the small part!

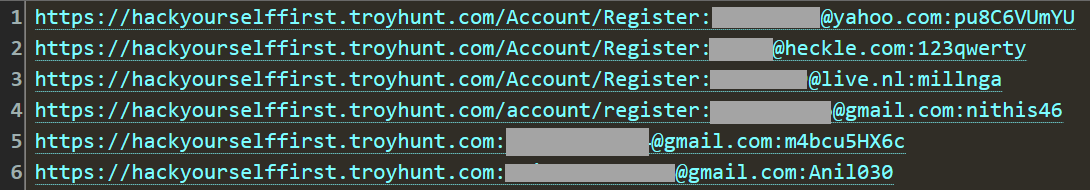

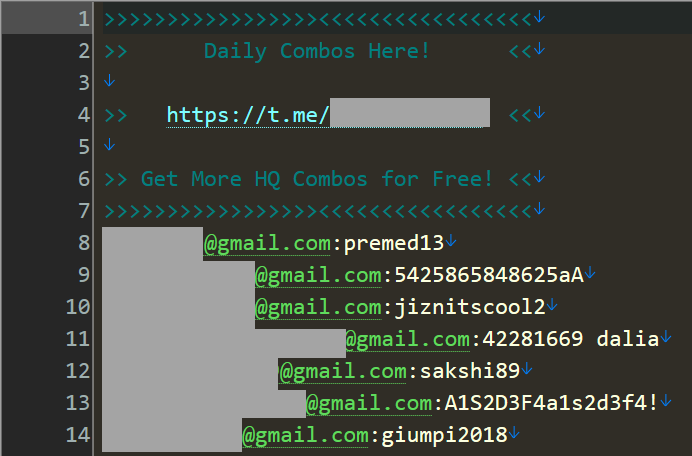

Ben's data also contained credential stuffing lists. Unlike stealer logs, which are the product of malware on the victim's machine, credential stuffing lists are typically aggregated from other places where email address and password pairs are obtained. For example, from data breaches where the passwords are either stored in plain text or protected with easily crackable hashing algorithms. Those lists are then used to access the other accounts of victims where they've reused their passwords.

Quick sidenote: Credential stuffing lists can be enormously damaging because they contain the keys to so many different services. Not only are they the gateway to so many takeovers of social media accounts, email addresses and other valuable personal resources, they're also responsible for many subsequent very serious data breaches. The 2017 Uber breach was attributed to previously breached employee credentials. Five years later, and the same approach provided the initial access to Uber again, after which MFA-bombing sealed the deal. Then there was the 23andMe breach in 2023, which was also traced back to credential stuffing. Similar but different was when Dunkin' Donuts had 20k customer details exposed in a show of how multifaceted this style of attack is: they were subsequently sued for not having sufficient controls to stop hackers from simply logging in with victims' legitimate credentials. It's wild; it's the attack that just keeps on giving.

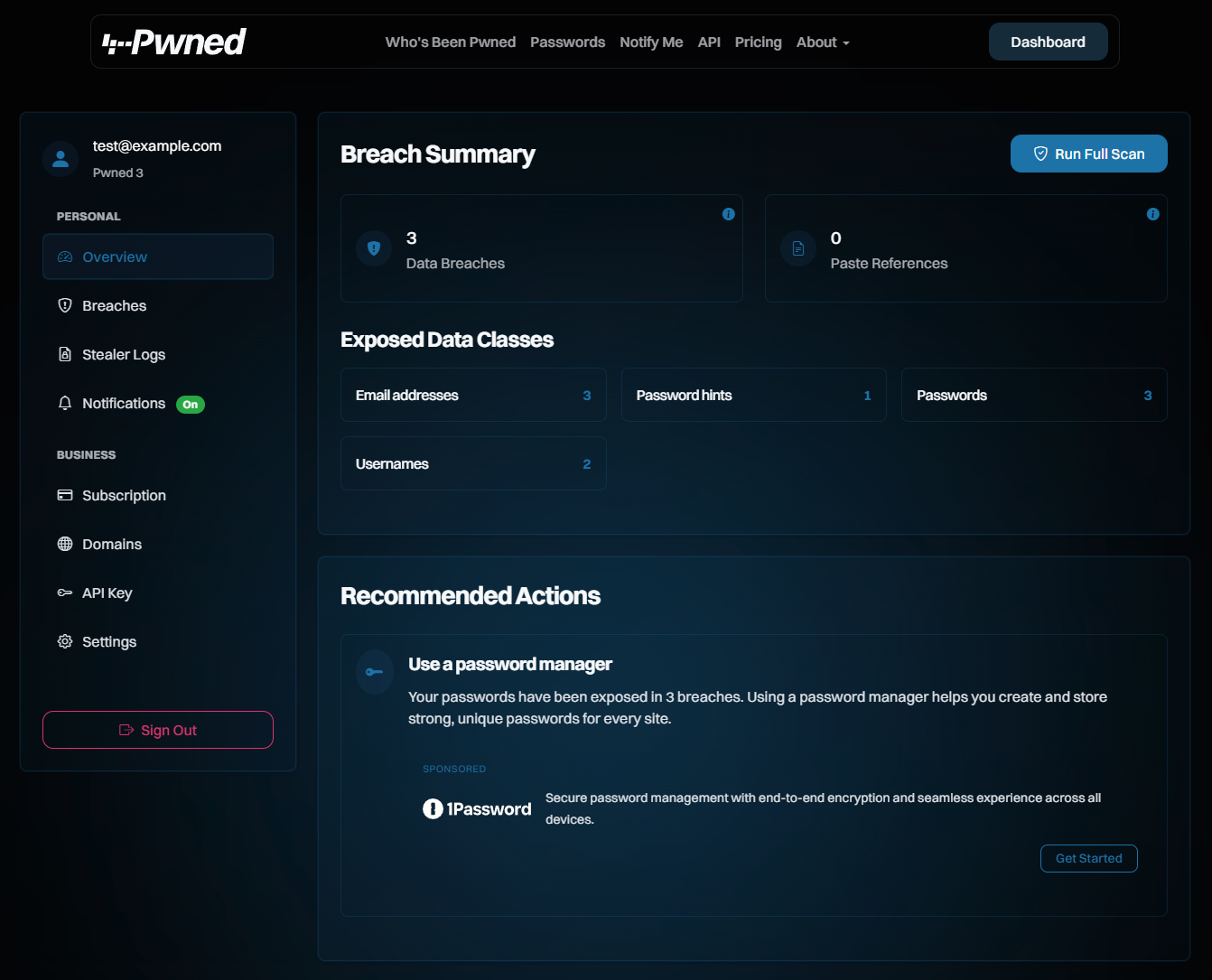

Ever since loading Collection #1 in 2019, I have been extra cautious about dealing with credential stuffing lists. The 400+ comments on that blog post will give you just a little taste of how much attention that exercise garnered. Frankly, it was a significant contributor to the feeling that it was all getting a bit too much, leading to the decision that HIBP needed to find another home (which fortunately, never eventuated). The primary issue with credential stuffing lists is that we can't attribute a given row to a specific source website or data breach, and we don't offer a service to look up credential pairs. As you'll see from many of the comments on that post, I had angry people upset that, without knowing specifically which password was exposed in the list, the knowledge that they were in there was not actionable. I disagree, because by loading those passwords into Pwned Passwords, there are now three easy ways to check if you're using a vulnerable one:

My vested interest in 1Password aside, Watchtower is the easiest, fastest way to understand your potential exposure in this incident. And in case you're wondering why I have so many vulnerable and reused passwords, it's a combination of the test accounts I've saved over the years and the 4-digit PINs some services force you to use. Would you believe that every single 4-digit number ever has been pwned?! (If you're interested, the ABC has a fantastic infographic using a heatmap based on HIBP data that shows some very predictable patterns for 4-digit PINs.)

As of the time of publishing this blog post, only the stealer logs have been loaded, and as mentioned earlier, the data in HIBP has been called "Synthient Stealer Log Threat Data". We intend to load the credential stuffing data as a separate corpus next week and call it "Synthient Credential Stuffing Threat Data", assuming it's sufficiently new and the accuracy is confirmed with our subscribers! We're doing this in two parts simply because of the scale of the data and the fact that we want to break it into two discrete corpuses given the data originates via different means. I'll revise this blog post accordingly after we finish our analysis.

Something that is becoming more evident as we load more stealer logs is that treating them as a discrete "breach" is not an accurate representation of how these things work. The truth is that, unlike a single data breach such as Ashley Madison, Dropbox, or the many other hundreds already in HIBP, stealer logs are more of a firehose of data that's just constantly spewing personal info all over the place. That, combined with the duplication of previously seen data, means that we need a rethink on this model. The data itself is still on point, but I'd like to see HIBP better reflect that firehose analogy and provide a constant stream of new data. Until then, Synthient's Threat Data will still sit in HIBP and be searchable in all the usual ways.

You see it all the time after a tragedy occurs somewhere, and people flock to offer their sympathies via the "thoughts and prayers" line. Sympathy is great, and we should all express that sentiment appropriately. The criticism, however, is that the line is often offered as a substitute for meaningful action. Responding to an incident with "thoughts and prayers" doesn't actually do anything, which brings us to court injunctions in the wake of a data breach.

Let's start with HWL Ebsworth, an Australian law firm that was the victim of a ransomware attack in 2023. They were granted an injunction, which means the following:

The final interlocutory injunction restrained hackers from the ALPHV, or “BlackCat”, hackers group from publishing the HWL data on the internet, sharing it with any person, or using the information for any reason other than for obtaining legal advice on the court’s orders.

To paraphrase, the injunction prohibits the Russian crime gang that hacked the law firm and attempted to extort them from publishing the data on the internet. Right... The threat actor was subsequently served with the injunction, to which, per the article, they responded in an entirely predictable fashion:

Fuck you fuckers

And then they dumped a huge trove of data. Clearly, criminals aren't going to pay any attention whatsoever to an injunction, but this legal construct has reach far beyond just the bad guys:

The injunction will also “assist in limiting the dissemination of the exfiltrated material by enabling HWLE to inform online platforms, who are at risk of publishing the material”, Justice Slattery said.

In other words, the data is also off limits to the good guys. Journalists, security firms and yes, Have I Been Pwned (HIBP) are all impacted by injunctions like this. To some extent, you can understand this when the data is as sensitive as what a law firm typically holds, and you need only use a little bit of imagination to picture how damaging it can be for data like this to fall into the wrong hands. But data in a breach of a company like Qantas is very different:

And now here’s mine. Still no indication of specifically which service was breached, but feels very much like loyalty program data (i.e. nothing to do with specific flights, password, passport or payment details). pic.twitter.com/r7KnlfM8TV

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) July 11, 2025

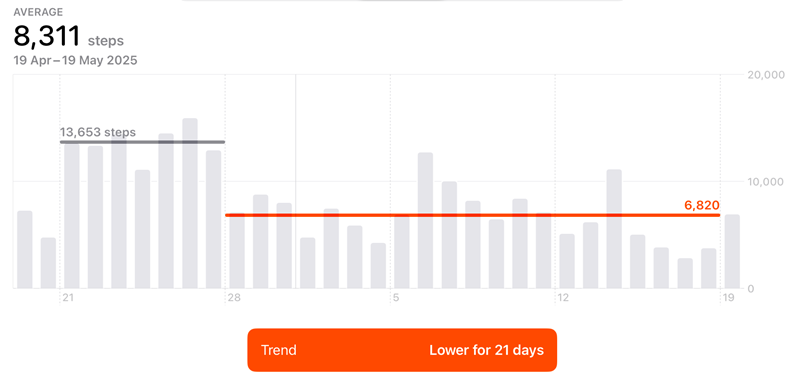

As well as my interest in running HIBP, I also appear to be a victim of their data breach, along with my wife and kids. And just to highlight how much skin I have in the game, I'm also a Qantas shareholder and a very loyal customer:

Sitting at the airport about to take my 301st (tracked) @Qantas flight. Nice banter with the staff: “you can lose my data, just don’t lose my bags” 😬 pic.twitter.com/ZGxc4I0aB1

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) July 2, 2025

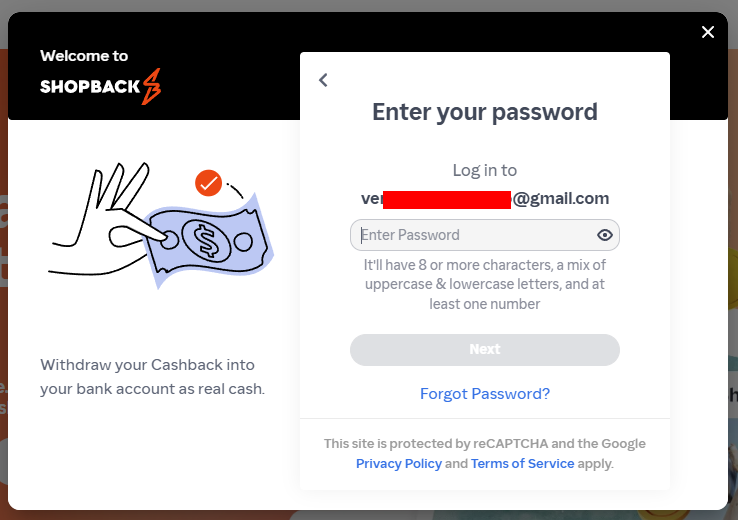

As such, I was particularly interested when they applied for, and were granted, a court injunction of their own. Why? What possible upside does this provide? Because by now, it's pretty clear what's going to happen to the data:

This is from a Telegram channel run by the group that took the Qantas data, along with some other huge names:

🚨🚨🚨BREAKING - New data leak site by Scattered LAPSUS$ Hunters exposes Salesforce customers. Dozens of global companies involved in a large-scale extortion campaign.

— Hackmanac (@H4ckmanac) October 3, 2025

Scattered LAPSUS$ Hunters claims to have breached Salesforce, exfiltrating ~1B records.

They accuse Salesforce… pic.twitter.com/u2PAO7miyP

"Scattered LAPSUS$ Hunters" is threatening to dump all the data publicly in a couple of days' time unless a ransom is paid, which it won't be. The quote from the Telegram image is from a Qantas spokesperson, and clearly, the injunction is not going to stop the publishing of data. Much of my gripe with injunctions is the premise that they in some way protect customers (like me), when clearly, they don't. But hey, "thoughts and prayers", right?

Without wanting to give too much credit to criminals attempting to ransom my data (and everyone else's), they're right about the media outlets. An injunction would have had a meaningful impact on the Ashley Madison coverage a decade ago, where the press happily outed the presence of famous people in the breach. Clearly, the Qantas data is nowhere near as newsworthy, and I can't imagine a headline going much beyond the significant point balances of certain politicians. The data just isn't that interesting.

The injunction is only effective against people who meet the following criteria:

The first two points are obvious, and an asterix adorns the third as it's very heavily caveated. This from a chat with a lawyer friend thir morning who specialises in this space:

it would depend on which country and whether it has a reciprocal agreement with Australia eg like the UK and also who you are trying it enforce it against and then it’s up to the court in that country to determine - but as this is an injunction (so not eg for a debt against a specific person) it’s almost impossible - you can’t just register a foreign judgement somewhere against the world at large as far as I know.

So, if the injunction is so useless at providing meaningful protections to data breach victims, what's the point? Who does it protect? In researching this piece, the best explanation I could find was from law firm Clayton Utz:

Where that confidentiality is breached due to a hack, parties should generally do - and be seen to be doing - what they can to prevent or minimise the extent of harm. Even if injunctions might not impact hackers, for the reasons set out above, they can provide ancillary benefits in relation to the further dissemination of hacked information by legitimate individuals and organisations. Depending on the terms, it might also assist with recovery on relevant insurance policies and reduce the risk of securities class actions being brought.

That term - "be seen to be doing" - says it all. This is now just me speculating, but I can envisage lawyers for Qantas standing up in court when they're defending against the inevitable class actions they'll face (which I also have strong views on), saying "Your honour, we did everything we could, we even got an injunction!" In a previous conversation I had regarding another data breach that had successfully been granted an injunction, I was told by the lawyer involved that they wanted to assure customers that they'd done everything possible. That breach was subsequently circulated online via a popular clear web hacking site (not "the dark web"), but I assume this fact and the ineffectiveness of the injunction on that audience was left out of customer communications. I feel pretty comfortable arguing that the primary beneficiary of the injunction is the shareholder, rather than the customer. And I assume the lawyers charge for their time, right?

Where this leaves us with Qantas is that, on a personal note, as a law-abiding Australian who is aware of the injunction, I won't be able to view my data or that of my kids. I can always request it of Qantas, of course, but I won't be able to go and obtain it if and when it's spread all over the internet. The criminals will, of course, and that's a very uncomfortable feeling.

From an HIBP perspective, we obviously can't load that data. It's very likely that hundreds of thousands of our subscribers will be impacted, and we won't be able to let them know (which is part of the reason I've written this post - so I can direct them here when asked). Granted, Qantas has obviously sent out disclosure notices to impacted individuals, but I'd argue that the notice that comes from HIBP carries a different gravitas: it's one thing to be told "we've had a security incident", and quite another to learn that your data is now in circulation to the extent that it's been sent to us. Further, Qantas won't be notifying the owners of the domains that their customers' email addresses are on. Many people will be using their work email address for their Qantas account, and when you tie that together with the other exposed data attributes, that creates organisational risk. Companies want to know when corporate assets (including email addresses) are exposed in a data breach, and unfortunately, we won't be able to provide them with that information.

I understand that Qantas' decision to pursue the injunction is about something much broader than the email addresses potentially appearing in HIBP. I actually think much of the advice Qantas has given is good, for example, the resources they've provided on their page about the breach:

These are all fantastic, and each of them has many good external resources people worried about scams should refer to. For example, ScamWatch has this one:

And cyber.gov.au has a handy tip courtesy of our Australian Signals Directorate makes this suggestion:

Not to miss a beat, our friends at IDCARE also offer great advice:

And, of course, the OAIC has some fantastic guidance too:

The scam resources Qantas recommends all link through to a service that will never return the Qantas data breach. Did I mention "thoughts and prayers" already?

As threatened, the Qantas data was dumped publicly 2 days after writing this post. The data appeared on a clear web file sharing service linked to by both their .onion website and a clear web site that popped up on a new domain shortly after the data was publicised. Due to the injunction, I've not accessed the data myself but have had security folks in other parts of the world reach out and confirm my record and that of my family members is present. I've also seen public commentary from other researchers analysing the data, and have had multiple people contact me and offer to send it.

Clearly, the injunction has proven to be extremely limited in its ability to stop the spread of data. Further, as a Qantas customer, I've not heard anything from them in relation to my data having now been publicly released. None of this should surprise anybody, including Qantas.

As to questions in the comments about the legitimacy of the injunction and where it can be obtained, the advice I've obtained from the law firm we use is that it is absolutely legitimate and interested parties would need to contact Qantas if they want to see it (likely a redacted version). I'm not savvy with the mechanics of how courts issue these and why they're not more publicly accessible, but I suggest this story with quotes from Justice Kunc is worth a read. Frankly, it's all a bit nuts, but that's the environment we're operating in and the rules we need to adhere to.

It's hard to explain the significance of CERN. It's the birthplace of the World Wide Web and the home of the largest machine ever built, the Large Hadron Collider. The bit that's hard to explain is, well, I mean, look at it!

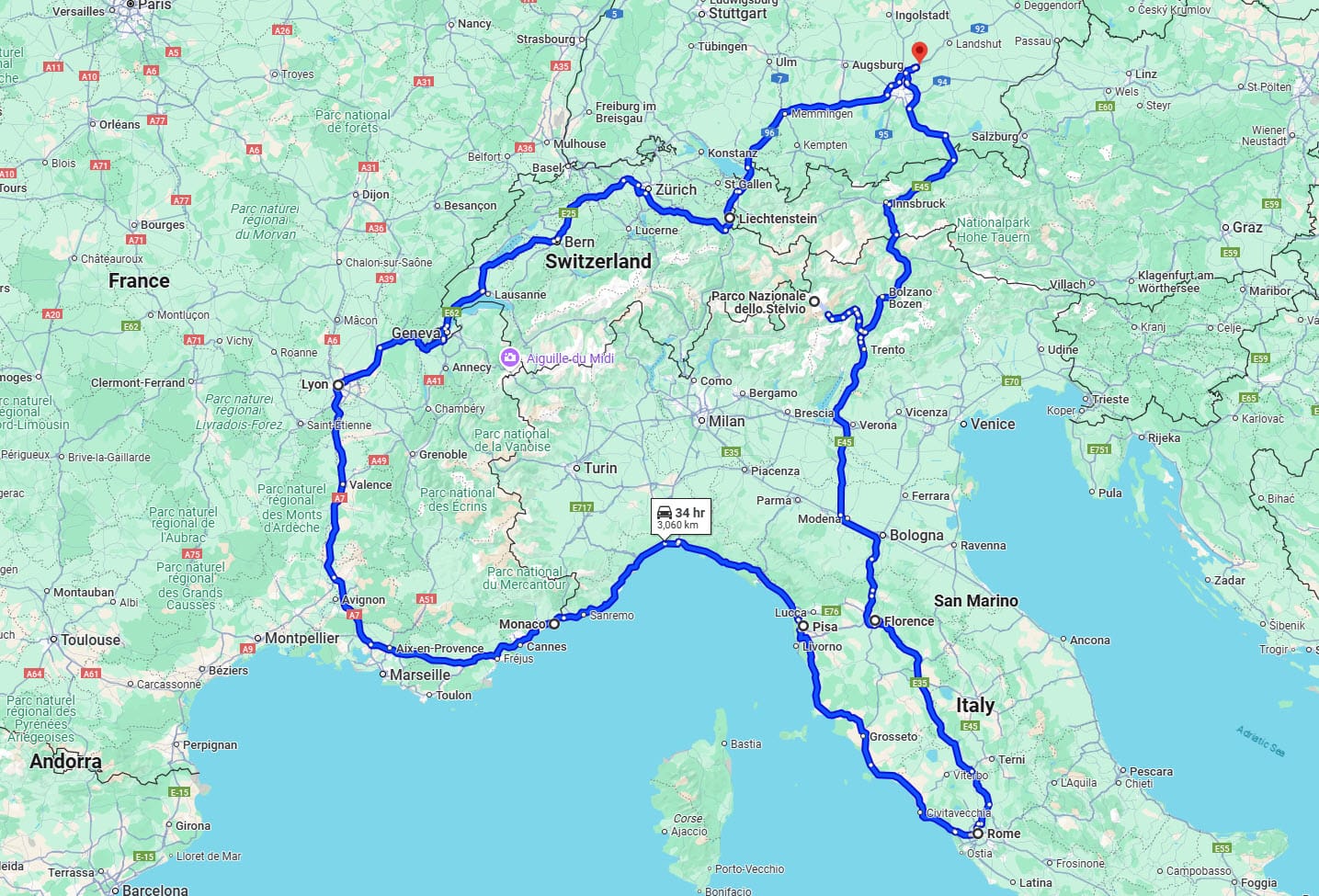

Charlotte and I visited CERN in 2019, nestled in there between Switzerland and France, and descended into the mountainside where we saw the world's largest particle accelerator firsthand. I can't explain this! The physics are just mind-bending.

A few months ago, we headed back there and saw even more stuff I can't explain:

How on earth do you make antimatter?! I know there's a lot of magnets involved, but that's about the limit of my understanding.

But what I do understand a little better is the importance of CERN. They're working to help humanity understand the most profound questions about the universe by exploring fundamental physics—the very building blocks of nature. And closer to my heart (or at least to my expertise), their role in the World Wide Web and the contribution CERN has made to the internet as we know it today cannot be overstated. It's also staffed by passionate individuals with a love of science that transcends borders and politics, including many from parts of the world that don't normally see eye-to-eye. This passion was evident on both our visits, and perhaps that's an extra poignant observation in a time with so much conflict.

In relation to HIBP and our ongoing support of governments, CERN is similar yet different. It's an intergovernmental organisation operating outside the jurisdiction of any one nation. However, they face the same online threats, and just like sovereign government states, their people sign up to services that get breached and end up in HIBP. And, like the governments we support, services that can be provided to help them tackle that threat are always appreciated. I was surprised to hear on our last visit that the sum total of contributions from their member states amounts to the price of a cup of coffee per person per year! For the work they do and the contribution they make to society, onboarding CERN as the 41st (inter)government was a no-brainer. They now have full and free access to query all CERN domains across the breadth of HIBP data. Welcome aboard CERN!

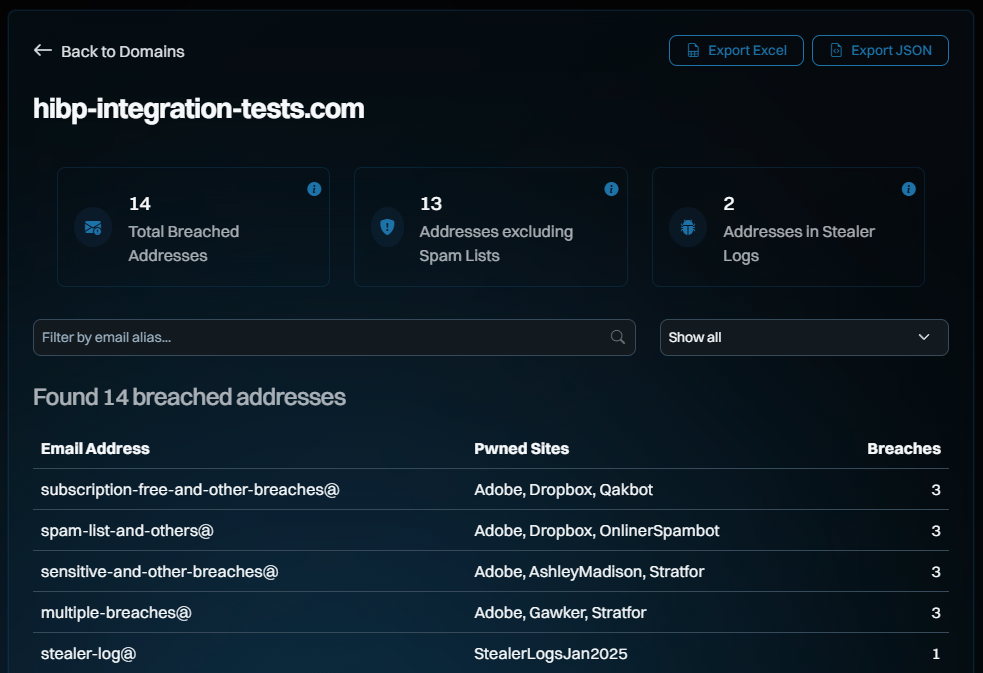

One of the most common use cases for HIBP's API is querying by email address, and we support hundreds of millions of searches against this endpoint every month. Loads of organisations use this service to understand the exposure of their customers and provide them with better protection against account takeover attacks. Many also use it to support customers who've already fallen victim - "hey, did you know HIBP says you're in 7 data breaches, any chance you've been reusing passwords?" Some companies even use it to help establish the legitimacy of an email address; we're all so pwned that if an address isn't pwned, maybe it isn't even real.

The latest video demo walks you through how to use this API and introduces something new that has been requested for years: a test API key. We've had this request so many times, and my response has usually been something to the effect of "mate, a key is a few bucks, just get a cheapie and start writing code". However, even if it were just a few cents, it would still pose a burden to some for various reasons. So, today we're also launching a test key:

hibp-api-key: 00000000000000000000000000000000The test key can only be used for queries against the test accounts (and we've had those for many years now), but it allows developers to start immediately writing code against the real live APIs. The technical implementation is identical to the key you get when you have a paid subscription, so this should help a bunch of people really fast-track their development and remove that one little barrier we previously had. Here's how it all works:

So, that's the breached account API, and it comes off the back of last week's first demo, showing how domain searches work. We've got a heap more to add yet and I'd love to hear about and others you feel would help you get the most out of the service.

Well, one of them is, but what's important is that we now have a platform on which we can start pushing out a lot more. It's not that HIBP is a particularly complex system that needs explaining in any depth, but we still get a lot of "how do I..." style questions for the fundamentals. Stuff like "how do I search our domain", which is why that's now the very first video we have in the series:

You'll also find this on the brand new demos page at haveibeenpwned.com/Demos where you'll soon be seeing many more examples that'll start with the basics, then become increasingly complex. The APIs in particular are the source of many support tickets, and we hope that these demos simplify them for the masses and save us some ticketing overhead in the process.

The demo is only five and a bit minutes, and I want to keep each one pretty succinct. If there's something you'd like to see explained, please drop me a comment below, and I'll do my best to create some material on it. In the meantime, check out the brand new HIBP YouTube channel and give it some love, there's a lot more coming.

Incidentally, in checking the stats whilst preparing this, it seems that we now have 357k instances of someone monitoring a domain 😲 That includes almost a quarter of the world's top 1k largest domains too, so this is a very heavily used feature and was a logical place to get started.

We were recently travelling to faraway lands, doing meet and greets with gov partners, when one of them posed an interesting idea:

What if people from our part of the world could see a link through to our local resource on data breaches provided by the gov?

Initially, I was sceptical, primarily because no matter where you are in the world, isn't the guidance the same? Strong and unique passwords, turn on MFA, and so on and so forth. But our host explained the suggestion, which in retrospect made a lot of sense:

Showing people a local resource from a trusted government body has a gravitas that we believe would better support data breach victims.

And he was right. Not just about the significance of a government resource, but as we gave it more thought, all the other things that are specific to the local environment. Additional support resources. Avenues to report scams. Language! Like literally, presenting content in a way that normal everyday folks can understand it based on where they are in the world. And we have the mechanics to do this now as we're already geo-targeting content on the breach pages courtesy of HIBP's partner program.

Whilst we're still working through the mechanics with the gov that initially came up with this suggestion, during a recent chat with our friends "across the ditch" at New Zealand's National Cyber Security Centre, I mentioned the idea. They thought it was great, so we just did it 🙂 As of now, if you're a Kiwi and you open up any one of the 899 breach pages (such as this one), you'll see this advice off to the right of the screen:

That links off to a resource on their Own Your Online initiative, which aims to help everyday folks there protect themselves in cyberspace. There's lots of good practical advice on the site along the lines I mentioned earlier, and even a suggestion to go and check out HIBP (which now links you back to the NZ NCSC...)

I'll be reaching out to our other gov partners around the world and seeing what resources they have that we could integrate, hopefully it's just one more little step in the right direction to protect the masses from online nasties.

Edit: As we add more local resources, I'll update this blog post with screen grabs and links, starting with our local Australian Signals Directorate:

We've now also added Bulgaria, complete with local language instructions:

I'm often asked if cyber criminals are getting better at impersonating legitimate organisations in order to sneak their phishing attacks through. Yes, they absolutely are, but I also argue that the inverse is true too: legitimate organisations frequently communicate in ways that are indistinguishable from a phishing attack! I can name countless examples of banks, delivery services and even government agencies sending communication that I was convinced was a phish, but turned out to be legit. I once had an argument with an agent from our own tax office on precisely that basis. After having shown all the hallmarks of being a scammer, she instead turned out to be making a legitimate inquiry. And if you need more convincing that even I can't tell the difference between a scam and legit comms, look no further than my own recent failure to spot a phish that successfully extracted my Mailchimp credentials, including the 2FA code!

I don't mind recognising that I struggle with scams, and frankly, it creates a lot more empathy for the masses out there who don't spend their days thinking about cybersecurity. These are the sorts of folks who use Have I Been Pwned and often land there a bit frazzled, looking for answers after learning they've been breached in some nasty incident. They need a proactive defence against this style of attack that can protect them when the human controls fail, as they recently failed me. That's why today, I'm very happy to announce a new HIBP partner, Guardio! You'll find them located on each dedicated breach page, and on the home page of your personal dashboard:

We've now turned the above recommendation on for all US-based visitors and highlighted them for all audiences regardless of locale on the partners page. We believe the service they offer makes a meaningful difference to the security posture of our users, and we are happy to include them here to complement the unique services provided by our existing partners. So it's a big welcome to Guardio, and I look forward to sharing more about the work they're doing to protect us all in the future. Check out what Guardio does on their dedicated HIBP page now.

If I'm honest, I was never that keen on a merch store for Have I Been Pwned. It doesn't make the code run faster, nor does it load any more data breaches or add any useful features to the service whatsoever. But... people were keen. They wanted swag they could wear or drink from or whatever, and it's actually pretty cool that there's excitement about HIBP as a brand. Plus, setting up a merch store is easy, right?

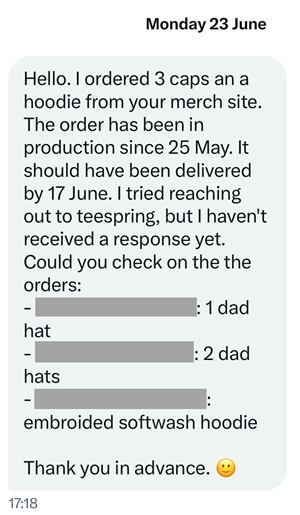

To cut to the chase, we set up a store on Teespring and they've been an absolute bloody disaster. Like, appalling bad to the point where we began to wonder if they're even legitimate, and I wish we had found a blog post like this before entrusting them with our brand. Initially, it was just dumb stuff like this:

FFS @teespringcom 🤦♂️ So far finding their support just appealing incompetent, this is regarding the @haveibeenpwned merch store, check out the canonical link: https://t.co/uHBeTlI1yU pic.twitter.com/nJBTGfCrqg

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) June 2, 2025

I mean, really dumb:

<link rel="canonical" href="https://0.0.0.0:3000" />So, everyone who visited the store and tried to share it via a mobile device was sending that address, and Teespring's response was that people should just manually copy and paste the URL! I stand by my reactions in that tweet - FFS 🤦♂️

Or on a similar note of technical incompetence, they were completely unable to add me to our store as an admin:

For those that come later and consider @teespringcom, don't even think about it! I've been trying to join the store @Charlotte_Hunt_ set up for us for 4 weeks ago now and the invite just gives a JSON response about failed CAPTCHA every time. Support is completely useless 😡 pic.twitter.com/d4EH6nC5O2

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) June 9, 2025

That support thread spanned from the 16th of May to the 12th of June and culminated in:

At this time, I still don’t have any updates from the Tech team. I understand this isn’t the resolution you were hoping for, and I sincerely apologize for the inconvenience and the delay.

And that's just the technical examples. The real pain came once we ordered merch, here's the timeline:

It's not just us either; not only have I not seen a single "hey, check out my cool HIBP merch" social post, I have received messages like this:

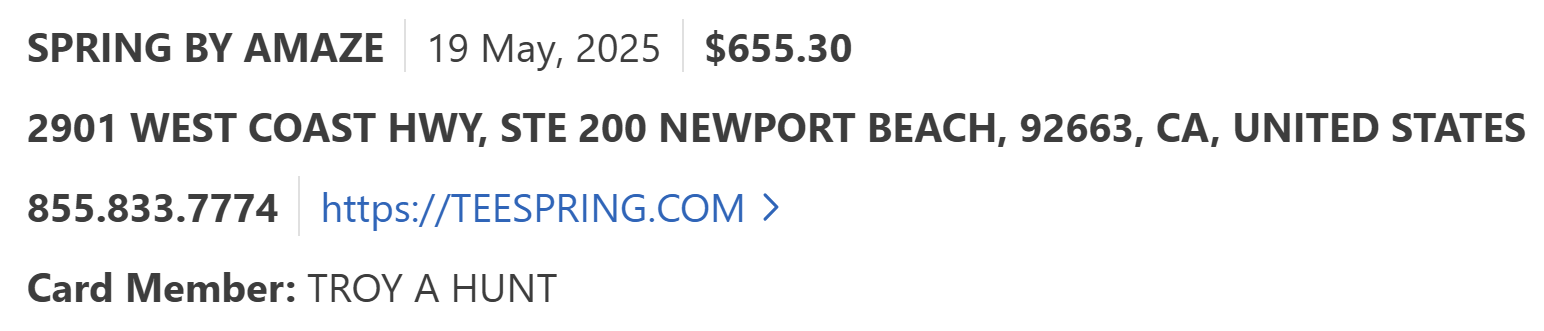

So, onto that dispute and believe it or not, this is the first time I've ever lodged a one. Turns out it's really simple, and I'd like to show everyone who made a purchase through the Teespring store just how easy it is. Firstly, I found the transaction on my Amex card:

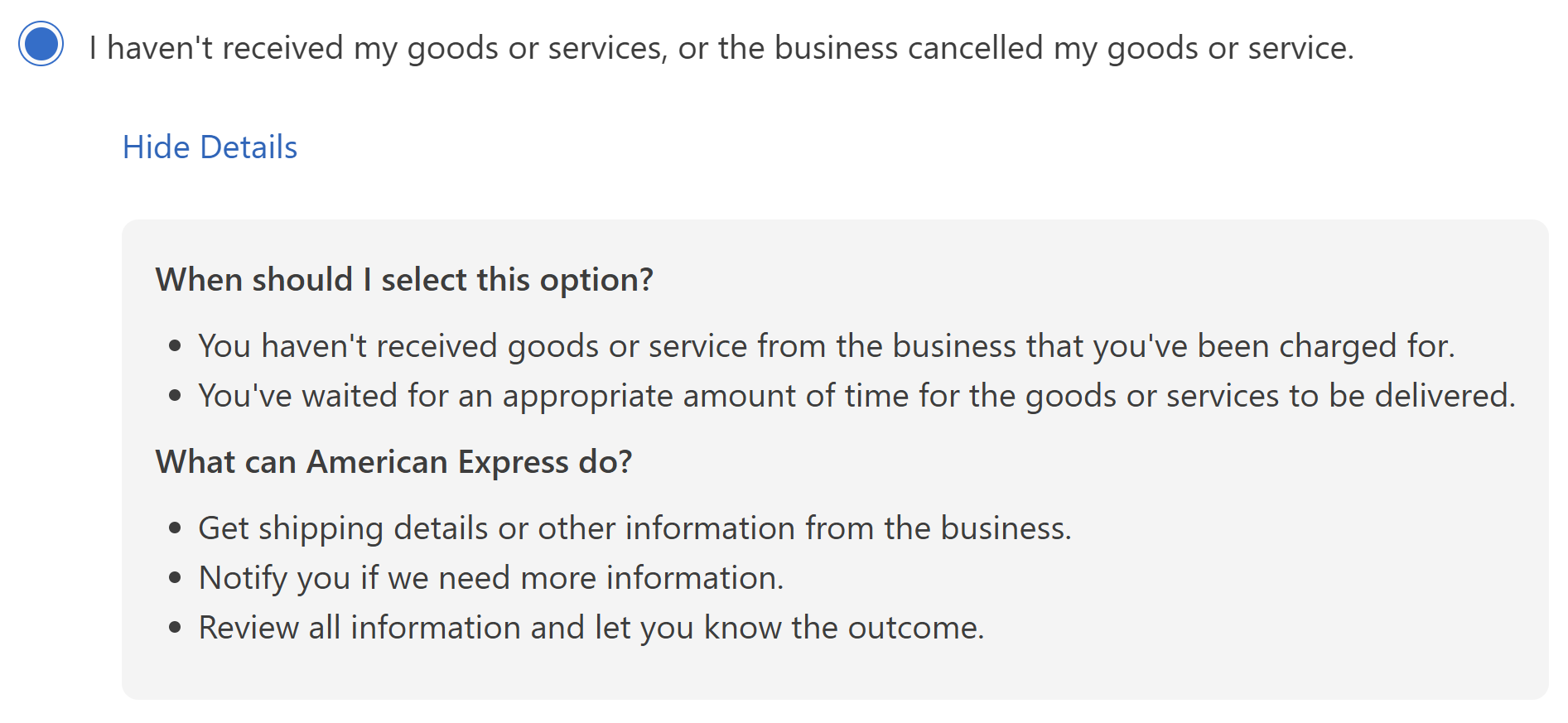

That record had an option to submit a dispute which then allowed me to choose a reason:

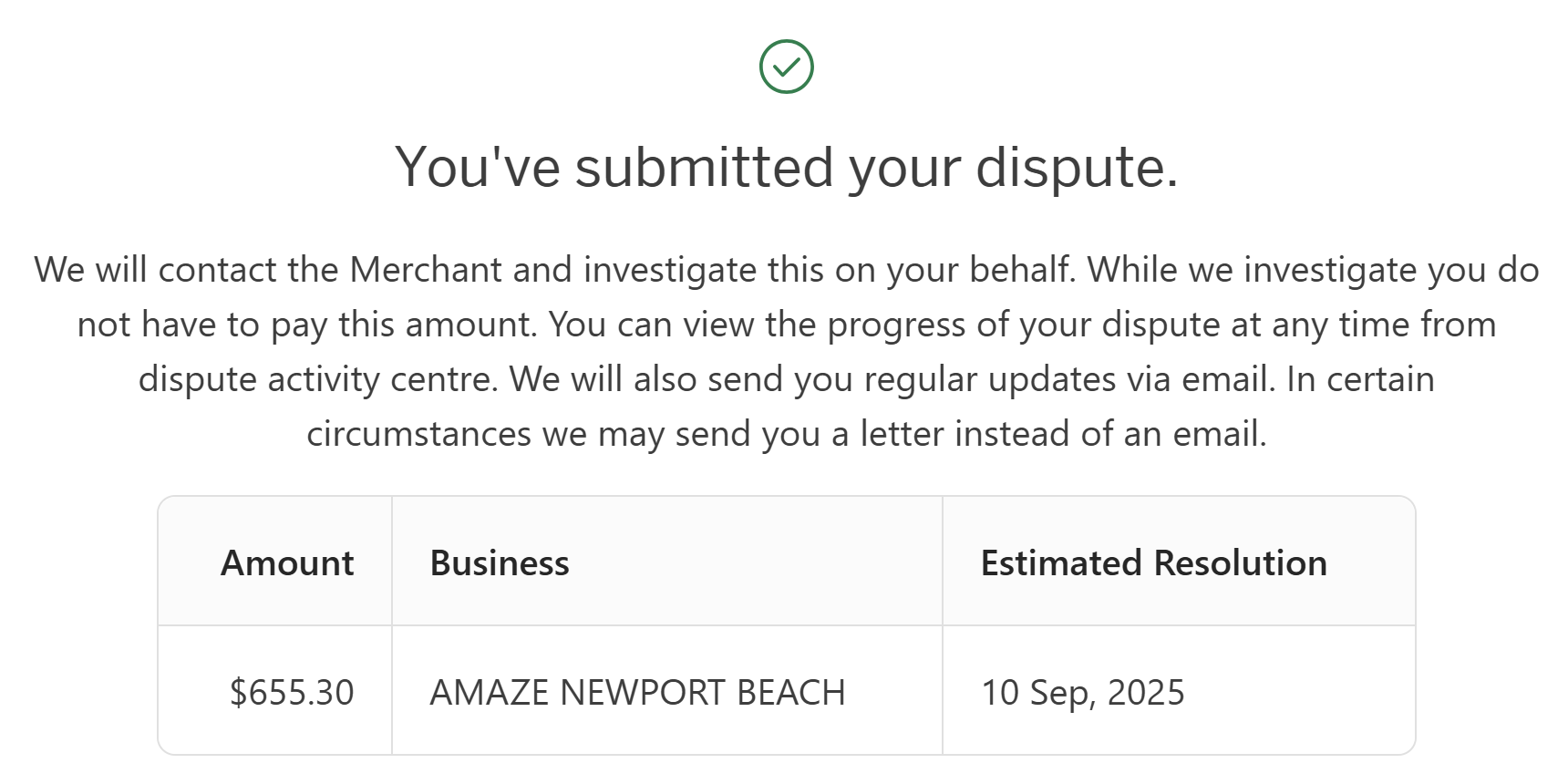

A few little questions in between (dates, attempts to contact them, etc), and we're done:

And just like that, Teespring suddenly found the ability to reply to support queries again!

We noticed a dispute was recently submitted for your transaction related to order #[reacted], with the reason noted as PRODUCT_NOT_RECEIVED. We wanted to reach out directly to better understand the situation and see how we can assist.

That came through yesterday, the 20th of July. As I think I've done a pretty decent job of outlining the situation in this blog post, we'll be sending them a link to it and following through with the dispute. Raising a dispute with your card provider not only returns the funds to your account, but it also levies a fee on the merchant, which in this case, seems entirely deserved.

I sincerely apologise to the HIBP supporters who trusted us enough to go to the merch store and make a purchase. This experience seriously sucks and should never have happened. I'll update this post with any further feedback I get from Teespring or Amex.

Onto more positive things, and an opportunity did arise out of Teespring's incompetence:

Happy to help you switch to Fourthwall. Shoot me a DM and we’ll move everything over for you

— Will Baumann (@dubbaumann) June 3, 2025

Usually, I'd be reluctant to respond to someone jumping in on a thread and pitching their product, but hey, we were desperate! And it turns out that Fourthwall is pretty awesome because people there actually talk to you and get stuff done 🙄 I mean, properly done:

We’ve got @haveibeenpwned merch! Arrived a little while ago and finally got into it today, we’ll keep adding more stuff to the store based on demand: https://t.co/uHBeTlI1yU pic.twitter.com/dQW7dcM0Ey

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) July 21, 2025

We ordered it on 2 July and received part of the order in Australia on 7 July, and the other part on 18 July. That's 5 and 16 days (both of which exceeded their estimate of 21-24 July), whilst the Teespring order was lodged 63 days ago 🤷♂️

So, check out merch.haveibeenpwned.com and have confidence that you will actually get what you order. Please leave a comment below if there's anything else you'd like to see in the store, and don't forget to pick up some nice thongs for yourself some nice thongs!

One of the greatest fears we all have in the wake of a data breach is having our identity stolen. Nefarious parties gather our personal information exposed in the breach, approach financial institutions and then impersonate us to do stuff like this:

So I recently somewhat had my identity stolen, someone used my driver's license to open about 10 different bank accounts across 6 Banks.

This was the message I received from a friend of mine just last week, and he was in a real mess. The bad guys had gotten so far into his real-life identity that not only were there a bunch of bank accounts now in his name, he was even having trouble proving who he was. Which makes sense when you think about it: once someone has the data attributes you use to verify your identity, how does a bank know that you're the real you? Like I said, it was a real mess, and he only found out about it after a lot of damage had already been done.

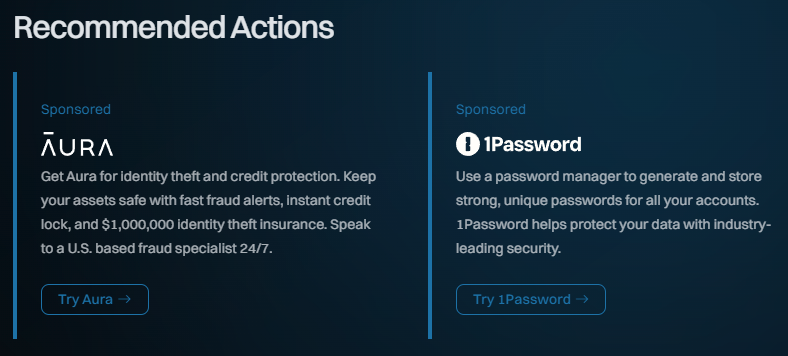

Which brings me to identity protection and, more specifically, Aura. I've known the folks there for years, and they were a sponsor of this blog for half a dozen weeks back in 2023. Their remit is to protect people from precisely the sort of outcomes my friend above suffered. They pride themselves on responding to fraud events super fast, providing 24/7 US-based customer support (that alone makes a massive difference), and even providing $1M American dollars in identity theft insurance. The US emphasis there is because, like Truyu who we recently onboarded to help Aussies, Aura is a geo-specific service and in this case, is there to help our friends in the US. As such, if you're coming to HIBP from that part of the world you'll see them appear in your dashboard and on the breach-specific pages:

Aura is there right alongside 1Password; two different companies offering two of the most valuable services to help protect you both before and after a data breach. And if you "Try Aura" per the link above, you'll land on their dedicated Have I Been Pwned page which provides you with a tasty discount.

Aura is a perfect example of the partnerships we've sought out to help make a positive difference to data breach victims, so a big welcome and thank you for providing the service they do.

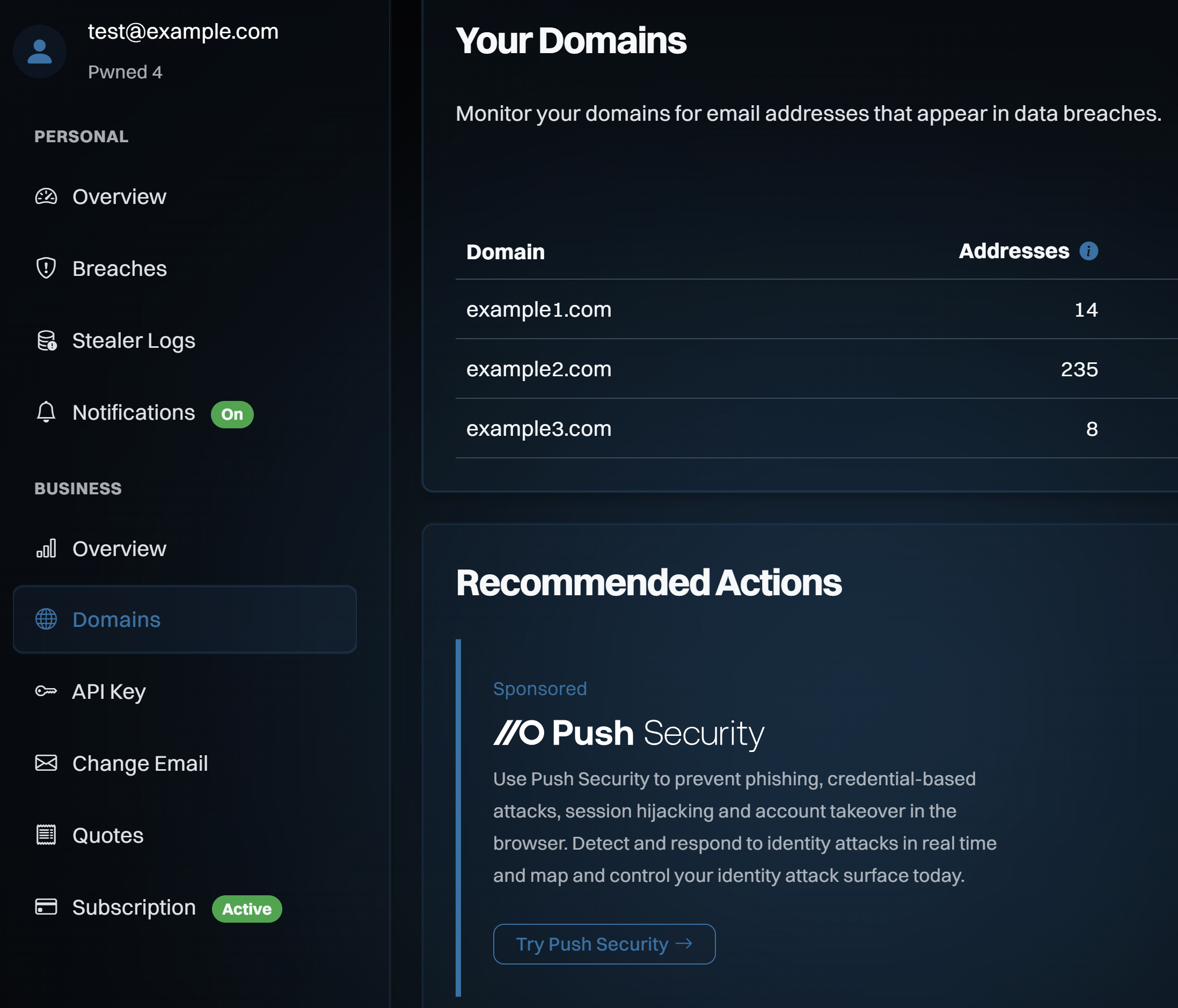

As we gradually roll out HIBP’s Partner Program, we’re aiming to deliver targeted solutions that bridge the gap between being at risk and being protected. HIBP is the perfect place to bring these solutions to the forefront, as it's often the point at which individuals and organisations first learn of their exposure in data breaches. The challenge for corporates, in particular, is especially significant as they're tasked with protecting entire workforces, often against highly motivated and sophisticated attackers seeking to exploit organisational vulnerabilities. That's why today, I'm especially happy to welcome Push Security to the program.

Push's mandate is to "defend workforce identities in the browser" from attacks that put corporate assets at risk. Especially within the context of data breaches, this includes attacks that leverage reused credentials (which often appear in breaches), account takeovers, phishing and session hijacking. Protecting organisations directly in the browser makes a lot of sense given how many attacks originate in that environment (something I'm painfully familiar with myself), and as they're fond of saying, "Push Security is like EDR but for the browser".

Because Push is focused on business solutions, they now have placement within the business section of the HIBP dashboard, namely the overview and domains pages:

I'm really happy with how we've been able to position partners in a way that's contextual, relevant and non-obtrusive. We've clearly marked Push as "Sponsored" and positioned them right at the heart of where those protecting organisatoins spend their time on HIBP.

Lastly, we've also now launched a dedicated partners page, which lists each relationship we have, including Push Security:

Regardless of where you are in the world, you'll see each partner, the pages on which they are displayed, and any geolocation dependencies. This ensures both transparency and exposure for the organisations we've entrusted to help protect users of our service.

So, a big welcome to Push Security and one more piece in the puzzle of protecting organisations from the scourge of data breaches.

I always used to joke that when people used Have I Been Pwned (HIBP), we effectively said "Oh no - you've been pwned! Uh, good luck!" and left it at that. That was fine when it was a pet project used by people who live in a similar world to me, but it didn't do a lot for the everyday folks just learning about the scary world of data breaches. Partnering with 1Password in 2018 helped, but the impact of data breaches goes well beyond the exposure of passwords, so a couple of months ago, I wrote about finding new partners to help victims "after the breach", Today, I'm very happy to welcome the first such partner, Truyu.

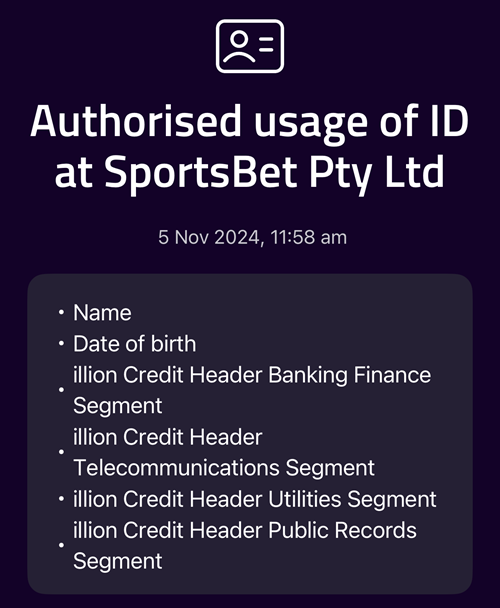

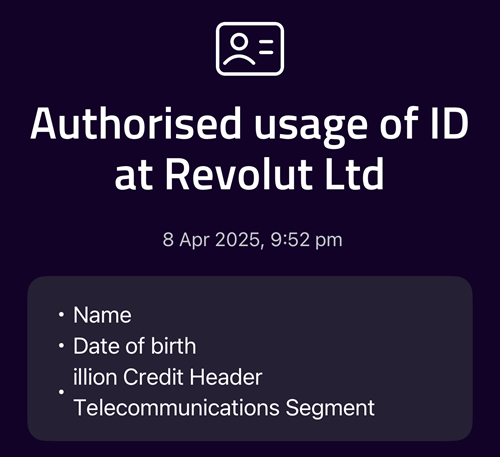

I alluded to Truyu being an excellent example of a potential partner in the aforementioned blog post, so their inclusion in this program should come as no surprise, but let me embellish further. In fact, let's start with something very topical as of the moment of posting:

New email from @Qantas just now: “we believe your personal information was accessed during the cyber incident”. They definitely deserve credit for early communication. pic.twitter.com/dTLlvI0Byq

— Troy Hunt (@troyhunt) July 2, 2025

It's pure coincidence that Qantas' incident coincides with the onboarding of an Aussie identity protection service, but it also makes it all the more relevant. My own personal circumstances are a perfect example: apparently, my name, email address, phone number, date of birth, and frequent flyer number are now in the hands of a hacking group not exactly known for protecting people's privacy. In the earlier blog post about onboarding new partners, I showed how Truyu had sent me early alerts when my identity data was used to sign up for a couple of different financial services. If that happens as a result of the Qantas breach, at least I'm going to know about it early.

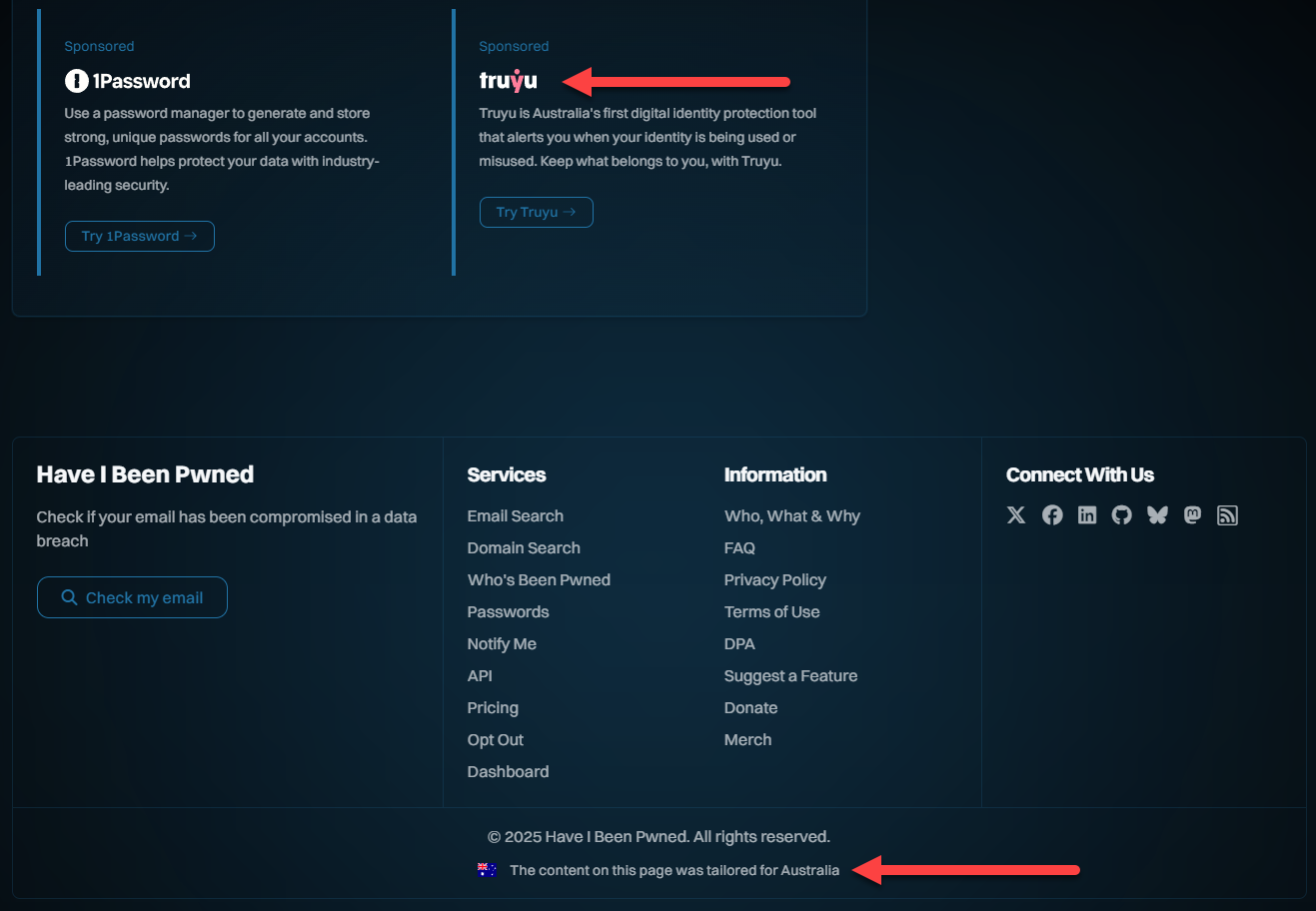

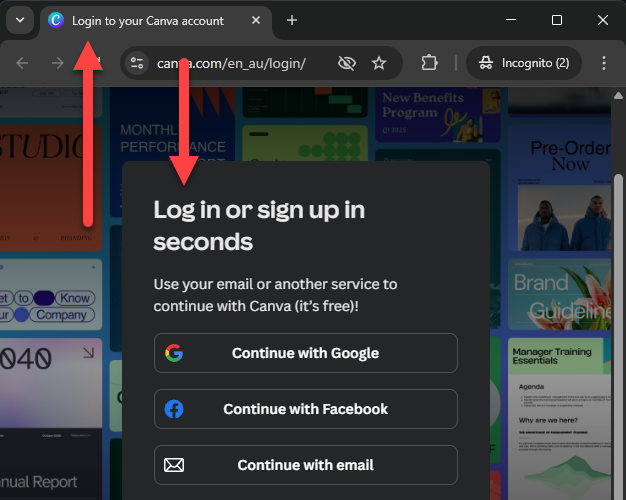

The introduction of Truyu as the first of several upcoming partners heralds the first time we've tailored content based on the geolocation of the user. What that means is that depending on where you are in the world, you may see something different to this:

I'm seeing Truyu on the Dropbox breach page because I'm in Australia, and if you're not, you won't. You'll have your own footer with your own country, which is based on Cloudflare's IP geolocation headers. In time, depending on where you are in the world, you'll see more content tailored specifically for you where it's relevant to your location. That's not just product placements either, we'll be adding other resources I'll share more about shortly.

Putting another brand name on HIBP is not something I take lightly, as is evidenced by the fact this is only the second time I've done this in nearly 12 years. Truyu is there because it's a product I genuinely believe provides value to data breach victims and in this case, one I also use myself. And for what it's worth, I've also spent time with the Truyu team in person on multiple occasions and have only positive things to say about them. That, in my book, goes a long way.

So, that's our new partner, and they've arrived at just the perfect time. Now I'm off to jump on a Qantas flight, wish me luck!

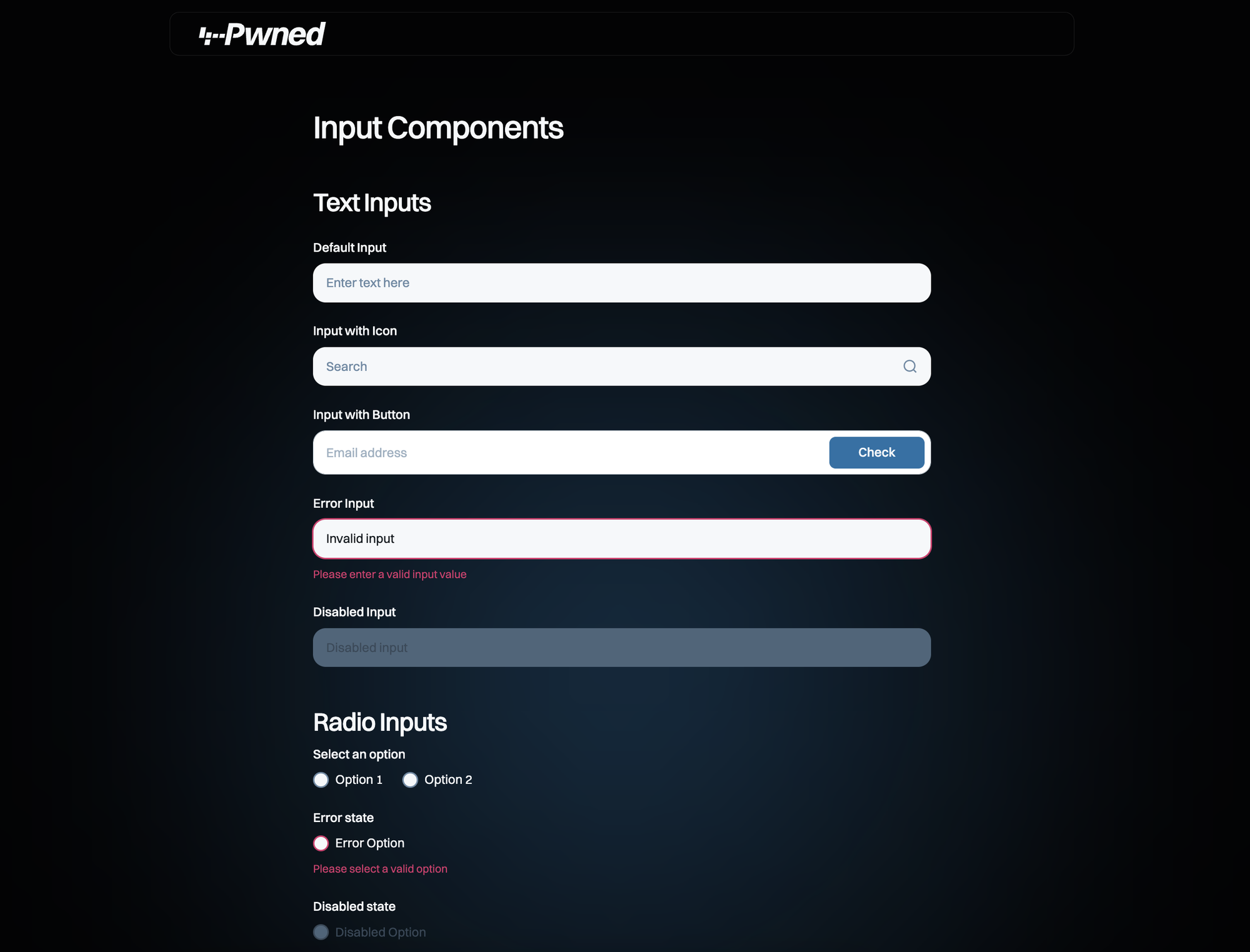

This has been a very long time coming, but finally, after a marathon effort, the brand new Have I Been Pwned website is now live!

Feb last year is when I made the first commit to the public repo for the rebranded service, and we soft-launched the new brand in March of this year. Over the course of this time, we've completely rebuilt the website, changed the functionality of pretty much every web page, added a heap of new features, and today, we're even launching a merch store 😎

Let me talk you through just some of the highlights, strap yourself in!

The signature feature of HIBP is that big search box on the front page, and now, it's even better - it has confetti!

Well, not for everyone, only about half the people who use it will see a celebratory response. There's a reason why this response is intentionally jovial, let me explain:

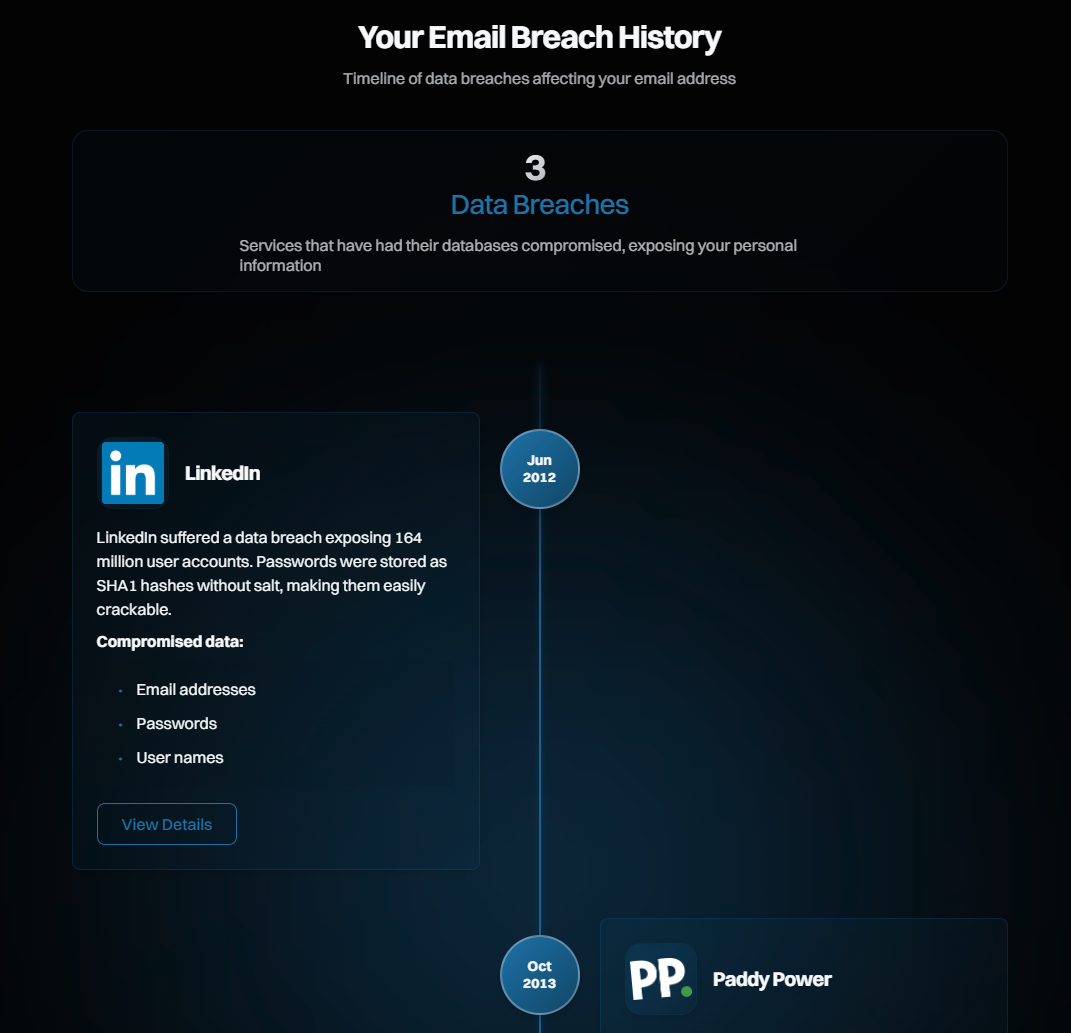

As Charlotte and I have travelled and spent time with so many different users of the service around the world, a theme has emerged over and over again: HIBP is a bit playful. It's not a scary place emblazoned with hoodies, padlock icons, and fearmongering about "the dark web". Instead, we aim to be more consumable to the masses and provide factual, actionable information without the hyperbole. Confetti guns (yes, there are several, and they're animated) lighten the mood a bit. The alternative is that you get the red response:

There was a very brief moment where we considered a more light-hearted treatment on this page as well, but somehow a bit of sad trombone really didn't seem appropriate, so we deferred to a more demure response. But now it's on a timeline you can scroll through in reverse chronological order, with each breach summarising what happened. And if you want more info, we have an all-new page I'll talk about in a moment.

Just one little thing first - we've dropped username and phone number search support from the website. Username searches were introduced in 2014 for the Snapchat incident, and phone number searches in 2021 for the Facebook incident. And that was it. That's the only time we ever loaded those classes of data, and there are several good reasons why. Firstly, they're both painful to parse out of a breach compared to email addresses, which we simply use a regex to extract (we've open sourced the code that does this). Usernames are a string. Phone numbers are, well, it depends. They're not just numbers because if you properly internationalise them (like they were in the Facebook incident), they've also got a plus at the front, but they're frequently all over the place in terms of format. And we can't send notifications because nobody "owns" a username, and phone numbers are very expensive to send SMSs to compared to sending emails. Plus, every other incident in HIBP other than those two has had email addresses, so if we're asking "have I been pwned?" we can always answer that question without loading those two hard-to-parse fields, which usually aren't present in most breaches anyway. When the old site offered to accept them in the search box, it created confusion and support overhead: "why wasn't my number in the [whatever] breach?!". That's why it's gone from the website, but we've kept it supported on the API to ensure we don't break anything... just don't expect to see more data there.

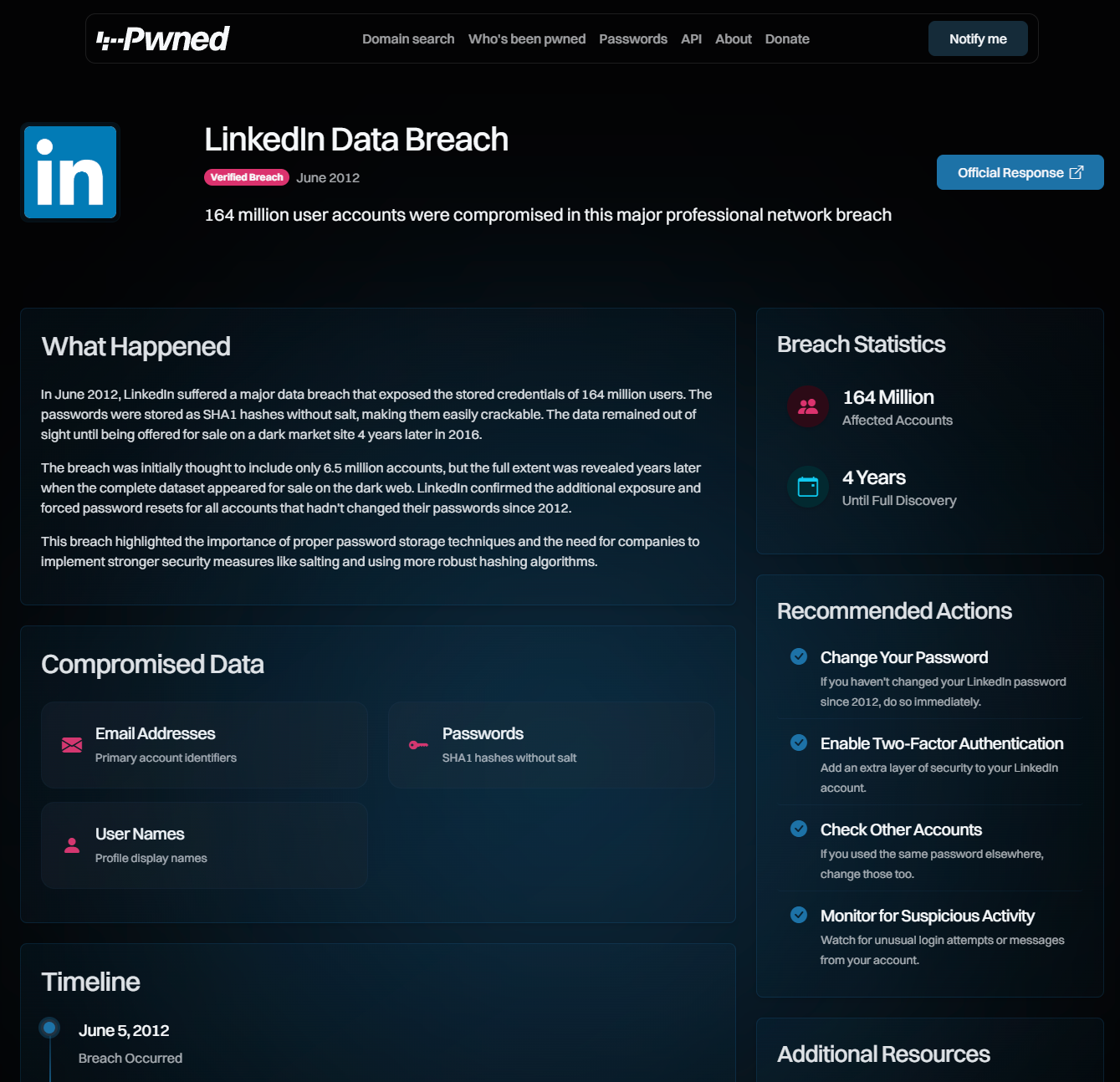

There are many reasons we created this new page, not least of which is that the search results on the front page were getting too busy, and we wanted to palm off the details elsewhere. So, now we have a dedicated page for each breach, for example:

That's largely information we had already (albeit displayed in a much more user-friendly fashion), but what's unique about the new page is much more targeted advice about what to do after the breach:

I recently wrote about this section and how we plan to identify other partners who are able to provide appropriate services to people who find themselves in a breach. Identity protection providers, for example, make a lot of sense for many data breaches.

Now that we're live, we'll also work on fleshing this page out with more breach and user-specific data. For example, if the service supports 2FA, then we'll call that out specifically rather than rely on the generic advice above. Same with passkeys, and we'll add a section for that. A recent discussion with the NCSC while we were in the UK was around adding localised data breach guidance, for example, showing folks from the UK the NCSC logo and a link to their resource on the topic (which recommends checking HIBP 🙂).

I'm sure there's much more we can do here, so if you've got any great ideas, drop me a comment below.

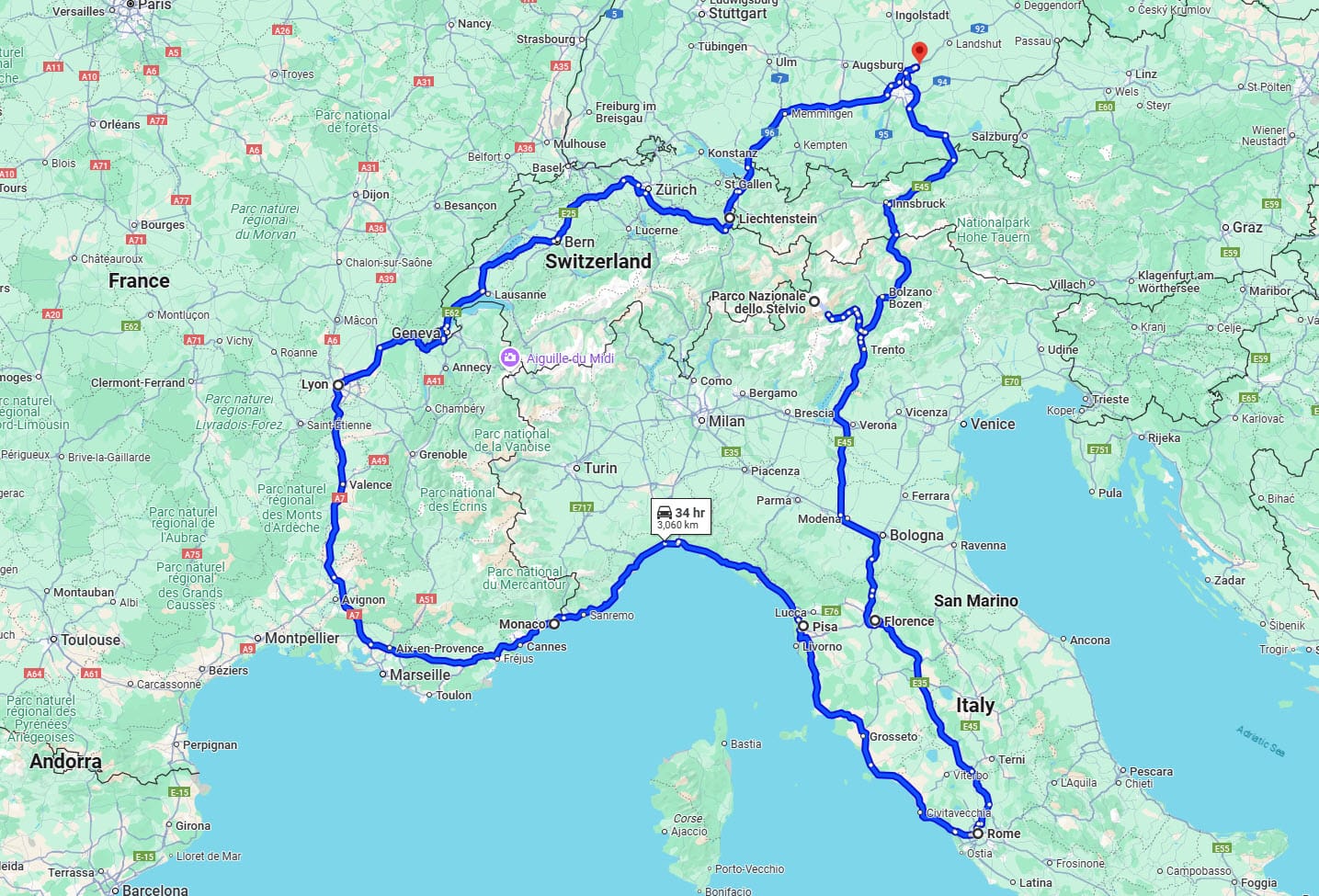

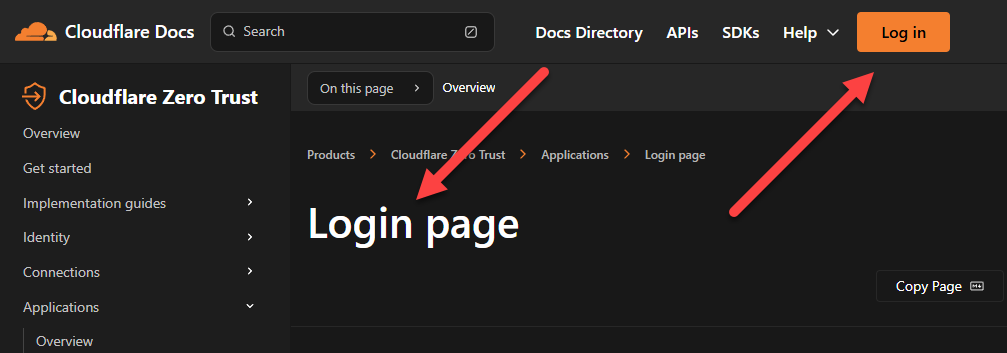

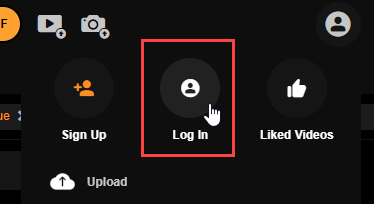

Over the course of many years, we introduced more and more features that required us to know who you were (or at least that you had access to the email address you were using). It began with introducing the concept of a sensitive breach during the Ashley Madison saga of 2015, which meant the only way to see your involvement in that incident was to receive an email to the address before searching. (Sidenote: There are many good reasons why we don't do that on every breach.) In 2019, when I put an auth layer around the API to tackle abuse (which it did beautifully!) I required email verification first before purchasing a key. And more things followed: a dedicated domain search dashboard, managing your paid subscription and earlier this year, viewing stealer logs for your email address.

We've now unified all these different places into one central dashboard:

From a glance at the nav on the left, you can see a lot of familiar features that are pretty self-explanatory. These combine relevant things for the masses and those that are more business-oriented. They're now all behind the one "Sign In" that verifies access to the email address before being shown. In the future, we'll also add passkey support to avoid needing to send an email first.

The dashboard approach isn't just about moving existing features under one banner; it will also give us a platform on which to build new features in the future that require email address verification first. For example, we've often been asked to provide people with the ability to subscribe their family's email addresses to notifications, yet have them go to a different address. Many of us play tech support for others, and this would be a genuinely useful feature that makes sense to place at a point where you've already verified your email address. So, stay tuned for that one, among many others.

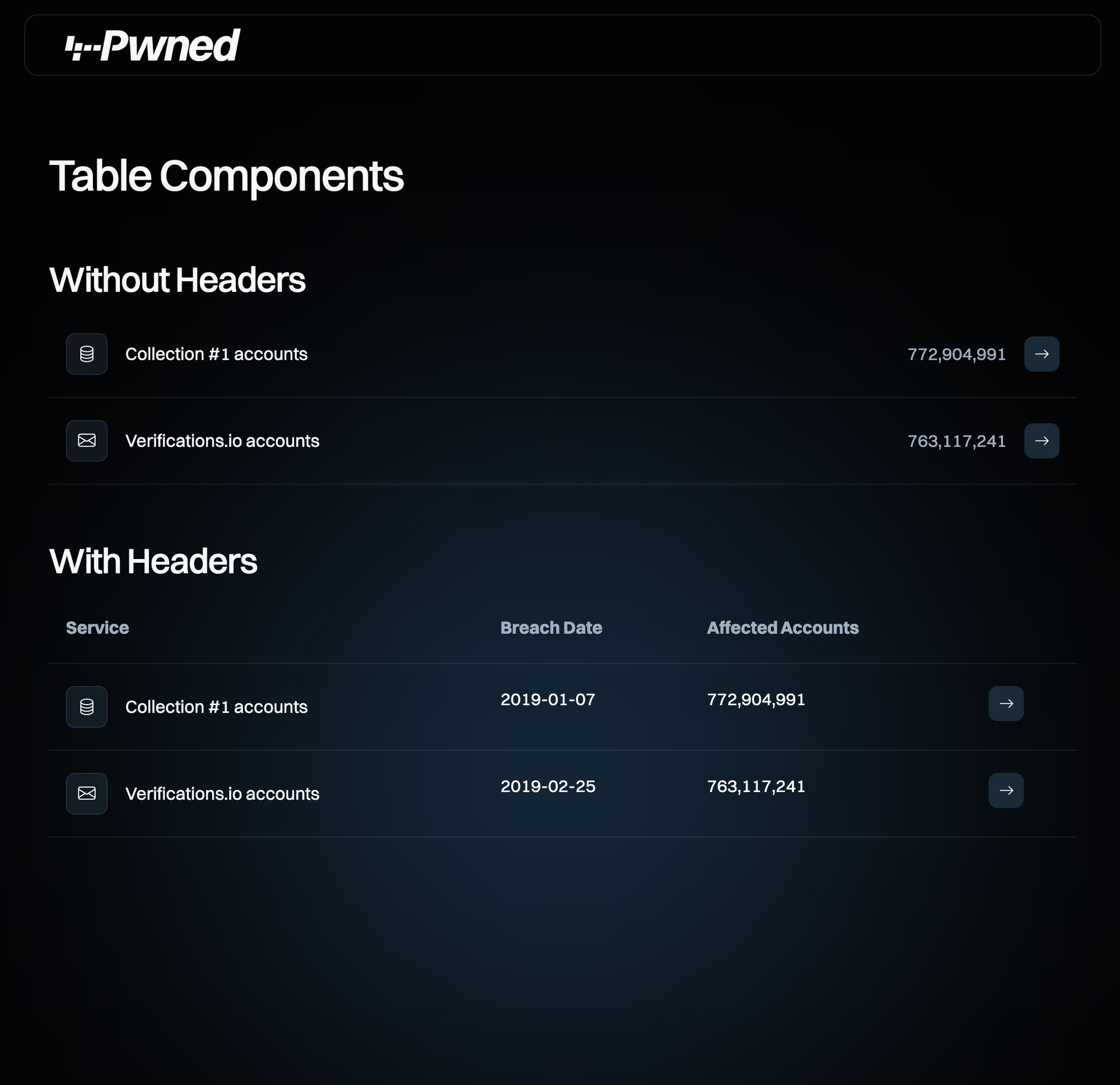

More time went into this one feature than most of the other ones combined. There's a lot we've tried to do here, starting with a much cleaner list of verified domains:

The search results now give a much cleaner summary and add filtering by both email address and a hotly requested new feature - just the latest breach (it's in the drop-down):

All those searches now just return JSON from APIs and the whole dashboard acts as a single-page app, so everything is really snappy. The filtering above is done purely client-side against the full JSON of the domain search, an approach we've tested with domains of over a quarter million breached email addresses and still been workable (although arguably, you really want that data via the API rather than scrolling through it in a browser window).

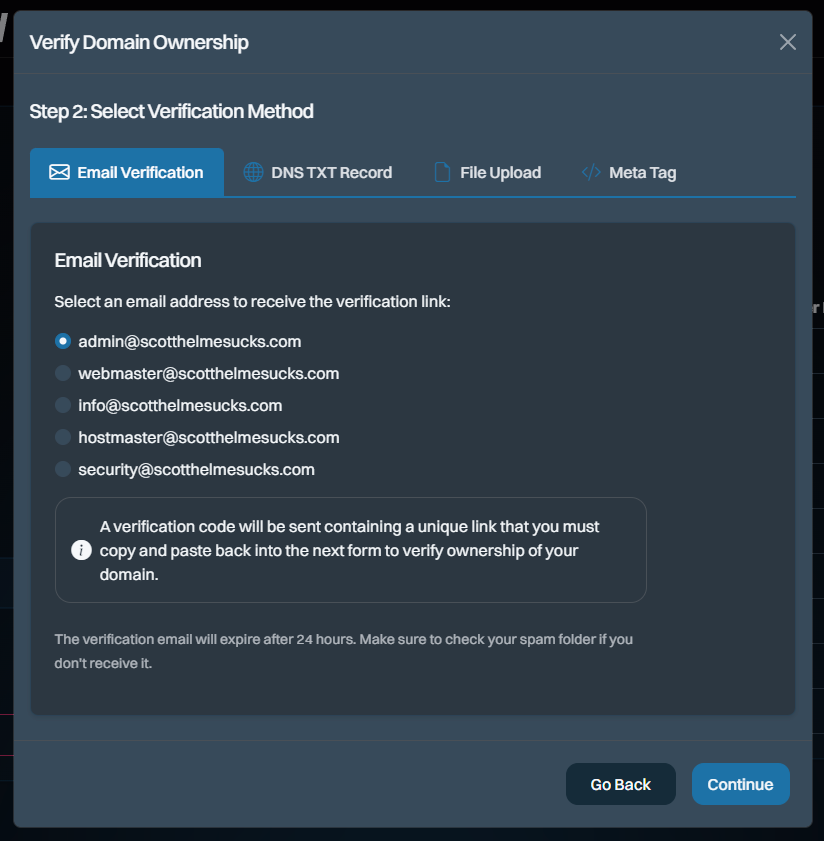

Verification of domain ownership has also been completely rewritten and has a much cleaner, simpler interface:

We still have work to do to make the non-email verification methods smoother, but that was the case before, too, so at least we haven't regressed. That'll happen shortly, promise!

First things first: there have been no changes to the API itself. This update doesn't break anything!

There's a discussion over on the UX rebuild GitHub repo about the right way to do API documentation. The general consensus is OpenAPI and we started going down that route using Scalar. In fact, you can even see the work Stefan did on this here at haveibeenpwned.com/scalar:

It's very cool, especially the way it documents samples in all sorts of different languages and even has a test runner, which is effectively Postman in the browser. Cool, but we just couldn't finish it in time. As such, we've kept the old documentation for now and just styled it so it looks like the rest of the site (which I reckon is still pretty slick), but we do intend to roll to the Scalar implementation when we're not under the duress of such a big launch.

You know what else is awesome? Merch! No, seriously, we've had so many requests over the years for HIBP branded merch and now, here we are:

We actually now have a real-life merch store at merch.haveibeenpwned.com! This was probably the worst possible use of our time, considering how much mechanical stuff we had to do to make all the new stuff work, but it was a bit of a passion project for Charlotte, so yeah, now you can actually buy HIBP merch. It's all done through Teespring (where have I heard that name before?!) and everything listed there is at cost price - we make absolutely zero dollars, it's just a fun initiative for the community 🙂

We did try out their option for stickers too, but they fell well short of what we already had up with our little one-item store on Sticker Mule so for now, that remains the go-to for laptop decorations. Or just go and grab the open source artwork and get your own printed from wherever you please.

We still run the origin services on Microsoft Azure using a combination of the App Service for the website, "serverless" Functions for most APIs (there are still a few async ones there that are called as a part of browser-based features), SQL Azure "Hyperscale" and storage account features like queues, blobs and tables. Pretty much all the coding there is C# with .NET 9.0 and ASP.NET MVC on .NET Core for the web app. Cloudflare still plays a massive role with a lot of code in workers, data in R2 storage and all their good bits around WAF and caching. We're also now exclusively using their Turnstile service for anti-automation and have ditched Google's reCAPTCHA completely - big yay!

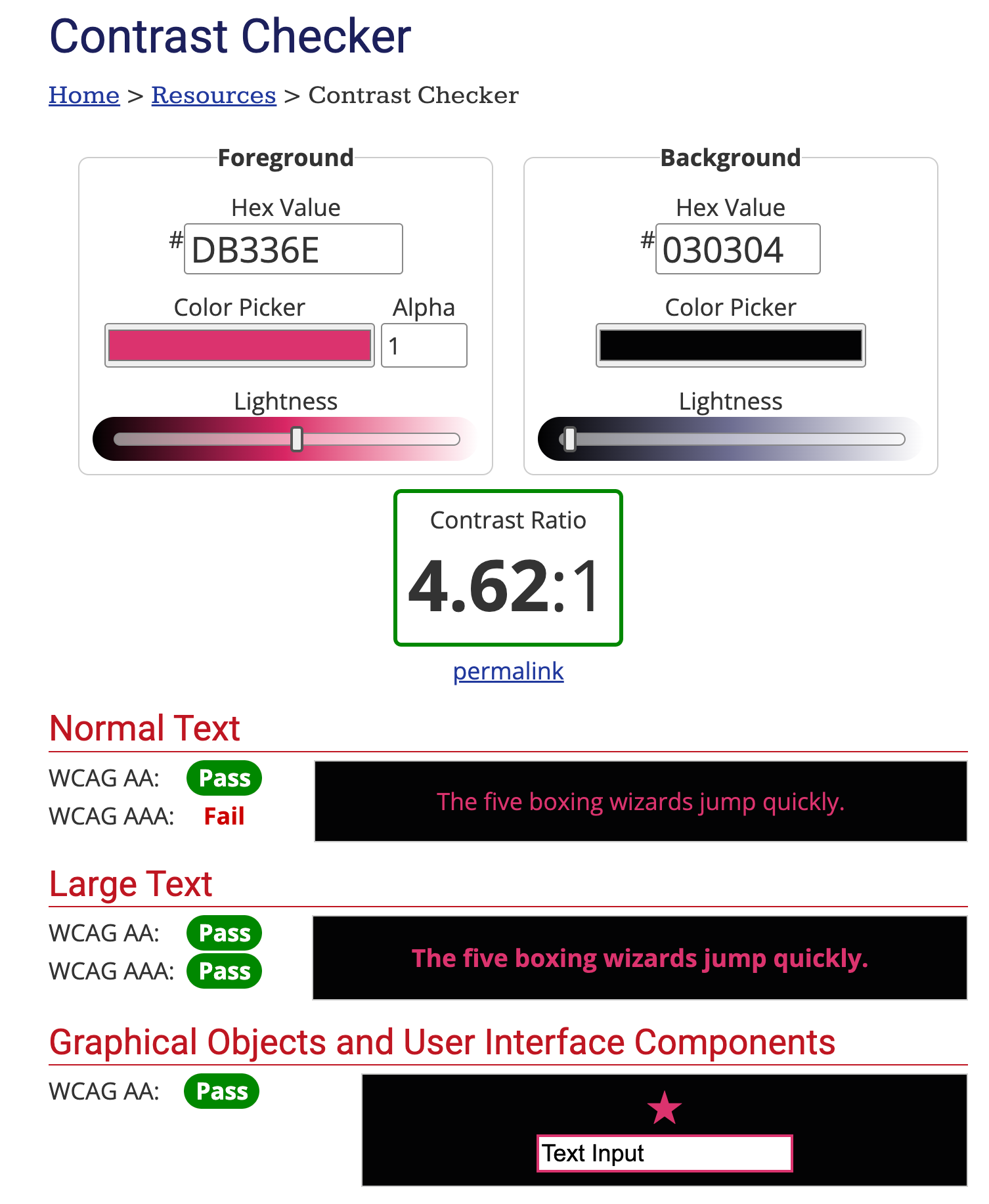

The front end is now latest gen Bootstrap and we're using SASS for all our CSS and TypeScript for all our JavaScript. Our (other) man in Iceland Ingiber has just done an absolutely outstanding job with the interfaces and exceeded all our expectations by a massive margin. What we have now goes far beyond what we expected when we started this process, and a big part of that has been Ingiber's ability to take a simple requirement and turn it into a thing of beauty 😍 I'm very glad that Charlotte, Stefan and I got to spend time with him in Reykjavik last month and share some beers.

We also made some measurable improvements to website performance. For example, I ran a Pingdom website speed test just before taking the old one offline:

And then ran it over the new one:

So we cut out 28% of the page size and 31% of the requests. The load time is much of a muchness (and it's highly variable at that), but having solid measures for all the values in the column on the right is a very pleasing result. Consider also the commentary anyone in web dev would have seen over the years about how much bigger web pages have become, and here we are shaving off solid double-digit percentages 11 years later!