The cybercriminals in control of Kimwolf — a disruptive botnet that has infected more than 2 million devices — recently shared a screenshot indicating they’d compromised the control panel for Badbox 2.0, a vast China-based botnet powered by malicious software that comes pre-installed on many Android TV streaming boxes. Both the FBI and Google say they are hunting for the people behind Badbox 2.0, and thanks to bragging by the Kimwolf botmasters we may now have a much clearer idea about that.

Our first story of 2026, The Kimwolf Botnet is Stalking Your Local Network, detailed the unique and highly invasive methods Kimwolf uses to spread. The story warned that the vast majority of Kimwolf infected systems were unofficial Android TV boxes that are typically marketed as a way to watch unlimited (pirated) movie and TV streaming services for a one-time fee.

Our January 8 story, Who Benefitted from the Aisuru and Kimwolf Botnets?, cited multiple sources saying the current administrators of Kimwolf went by the nicknames “Dort” and “Snow.” Earlier this month, a close former associate of Dort and Snow shared what they said was a screenshot the Kimwolf botmasters had taken while logged in to the Badbox 2.0 botnet control panel.

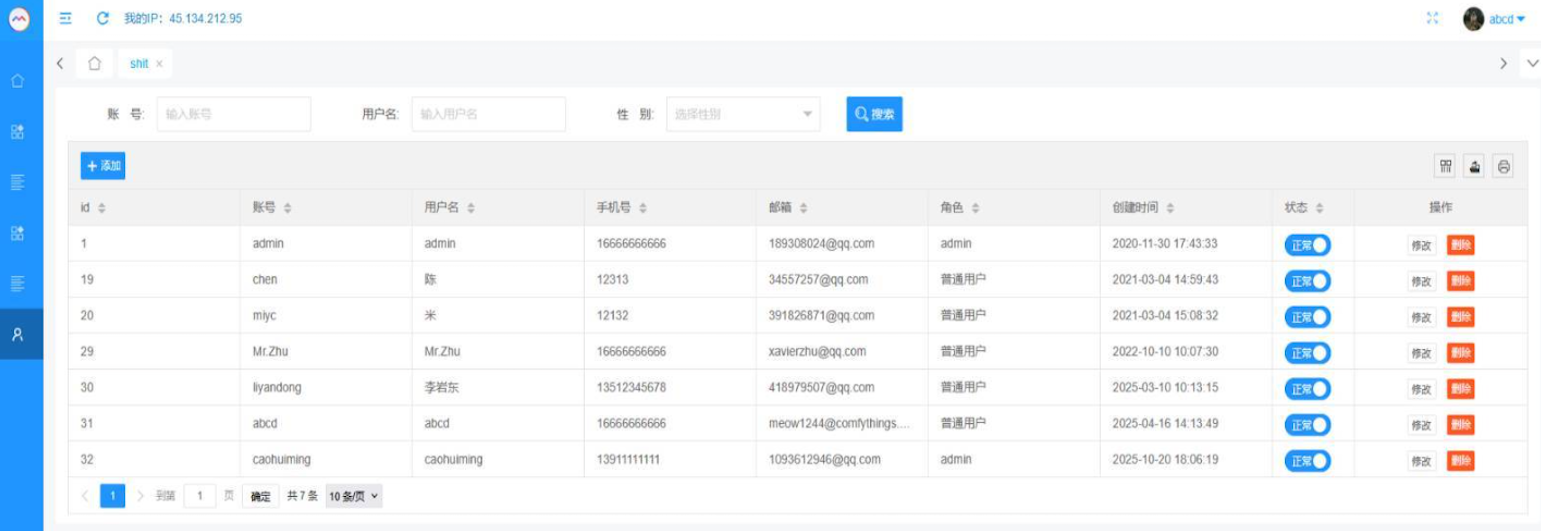

That screenshot, a portion of which is shown below, shows seven authorized users of the control panel, including one that doesn’t quite match the others: According to my source, the account “ABCD” (the one that is logged in and listed in the top right of the screenshot) belongs to Dort, who somehow figured out how to add their email address as a valid user of the Badbox 2.0 botnet.

The control panel for the Badbox 2.0 botnet lists seven authorized users and their email addresses. Click to enlarge.

Badbox has a storied history that well predates Kimwolf’s rise in October 2025. In July 2025, Google filed a “John Doe” lawsuit (PDF) against 25 unidentified defendants accused of operating Badbox 2.0, which Google described as a botnet of over ten million unsanctioned Android streaming devices engaged in advertising fraud. Google said Badbox 2.0, in addition to compromising multiple types of devices prior to purchase, also can infect devices by requiring the download of malicious apps from unofficial marketplaces.

Google’s lawsuit came on the heels of a June 2025 advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which warned that cyber criminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by either configuring the products with malware prior to the user’s purchase, or infecting the device as it downloads required applications that contain backdoors — usually during the set-up process.

The FBI said Badbox 2.0 was discovered after the original Badbox campaign was disrupted in 2024. The original Badbox was identified in 2023, and primarily consisted of Android operating system devices (TV boxes) that were compromised with backdoor malware prior to purchase.

KrebsOnSecurity was initially skeptical of the claim that the Kimwolf botmasters had hacked the Badbox 2.0 botnet. That is, until we began digging into the history of the qq.com email addresses in the screenshot above.

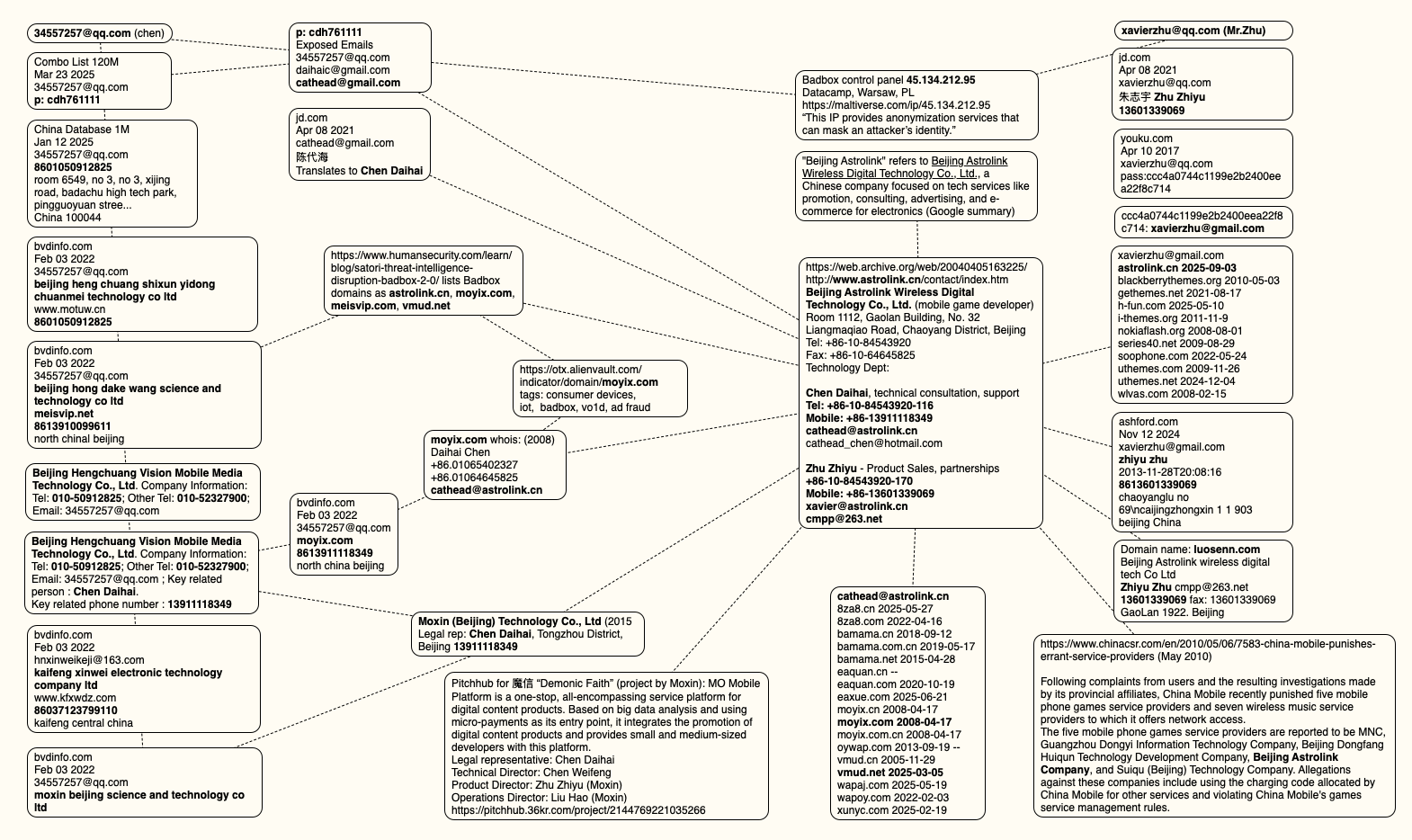

An online search for the address 34557257@qq.com (pictured in the screenshot above as the user “Chen“) shows it is listed as a point of contact for a number of China-based technology companies, including:

–Beijing Hong Dake Wang Science & Technology Co Ltd.

–Beijing Hengchuang Vision Mobile Media Technology Co. Ltd.

–Moxin Beijing Science and Technology Co. Ltd.

The website for Beijing Hong Dake Wang Science is asmeisvip[.]net, a domain that was flagged in a March 2025 report by HUMAN Security as one of several dozen sites tied to the distribution and management of the Badbox 2.0 botnet. Ditto for moyix[.]com, a domain associated with Beijing Hengchuang Vision Mobile.

A search at the breach tracking service Constella Intelligence finds 34557257@qq.com at one point used the password “cdh76111.” Pivoting on that password in Constella shows it is known to have been used by just two other email accounts: daihaic@gmail.com and cathead@gmail.com.

Constella found cathead@gmail.com registered an account at jd.com (China’s largest online retailer) in 2021 under the name “陈代海,” which translates to “Chen Daihai.” According to DomainTools.com, the name Chen Daihai is present in the original registration records (2008) for moyix[.]com, along with the email address cathead@astrolink[.]cn.

Incidentally, astrolink[.]cn also is among the Badbox 2.0 domains identified in HUMAN Security’s 2025 report. DomainTools finds cathead@astrolink[.]cn was used to register more than a dozen domains, including vmud[.]net, yet another Badbox 2.0 domain tagged by HUMAN Security.

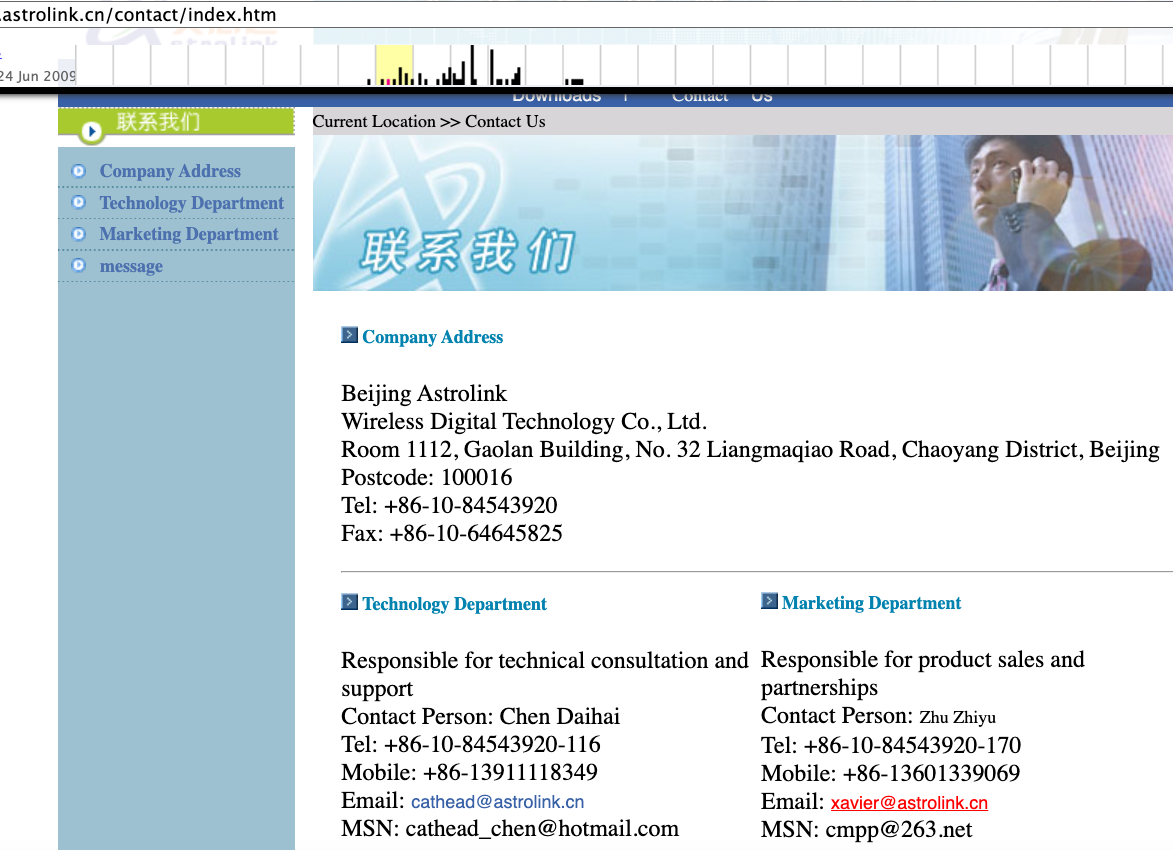

A cached copy of astrolink[.]cn preserved at archive.org shows the website belongs to a mobile app development company whose full name is Beijing Astrolink Wireless Digital Technology Co. Ltd. The archived website reveals a “Contact Us” page that lists a Chen Daihai as part of the company’s technology department. The other person featured on that contact page is Zhu Zhiyu, and their email address is listed as xavier@astrolink[.]cn.

A Google-translated version of Astrolink’s website, circa 2009. Image: archive.org.

Astute readers will notice that the user Mr.Zhu in the Badbox 2.0 panel used the email address xavierzhu@qq.com. Searching this address in Constella reveals a jd.com account registered in the name of Zhu Zhiyu. A rather unique password used by this account matches the password used by the address xavierzhu@gmail.com, which DomainTools finds was the original registrant of astrolink[.]cn.

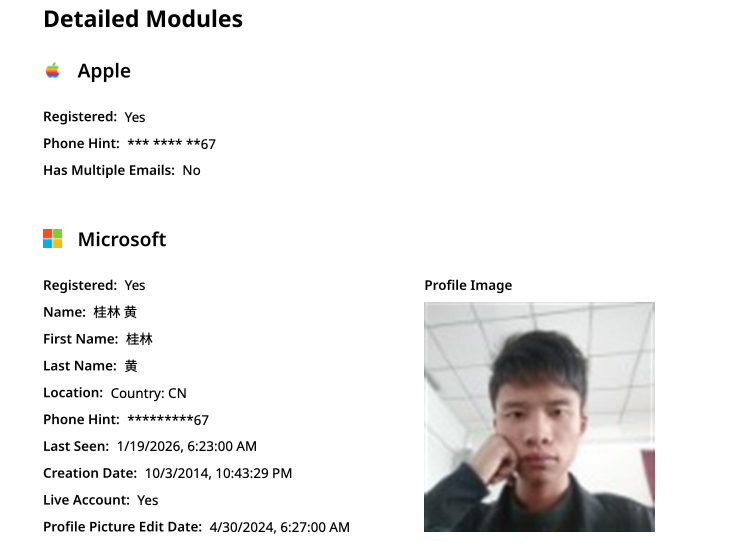

The very first account listed in the Badbox 2.0 panel — “admin,” registered in November 2020 — used the email address 189308024@qq.com. DomainTools shows this email is found in the 2022 registration records for the domain guilincloud[.]cn, which includes the registrant name “Huang Guilin.”

Constella finds 189308024@qq.com is associated with the China phone number 18681627767. The open-source intelligence platform osint.industries reveals this phone number is connected to a Microsoft profile created in 2014 under the name Guilin Huang (桂林 黄). The cyber intelligence platform Spycloud says that phone number was used in 2017 to create an account at the Chinese social media platform Weibo under the username “h_guilin.”

The public information attached to Guilin Huang’s Microsoft account, according to the breach tracking service osintindustries.com.

The remaining three users and corresponding qq.com email addresses were all connected to individuals in China. However, none of them (nor Mr. Huang) had any apparent connection to the entities created and operated by Chen Daihai and Zhu Zhiyu — or to any corporate entities for that matter. Also, none of these individuals responded to requests for comment.

The mind map below includes search pivots on the email addresses, company names and phone numbers that suggest a connection between Chen Daihai, Zhu Zhiyu, and Badbox 2.0.

This mind map includes search pivots on the email addresses, company names and phone numbers that appear to connect Chen Daihai and Zhu Zhiyu to Badbox 2.0. Click to enlarge.

The idea that the Kimwolf botmasters could have direct access to the Badbox 2.0 botnet is a big deal, but explaining exactly why that is requires some background on how Kimwolf spreads to new devices. The botmasters figured out they could trick residential proxy services into relaying malicious commands to vulnerable devices behind the firewall on the unsuspecting user’s local network.

The vulnerable systems sought out by Kimwolf are primarily Internet of Things (IoT) devices like unsanctioned Android TV boxes and digital photo frames that have no discernible security or authentication built-in. Put simply, if you can communicate with these devices, you can compromise them with a single command.

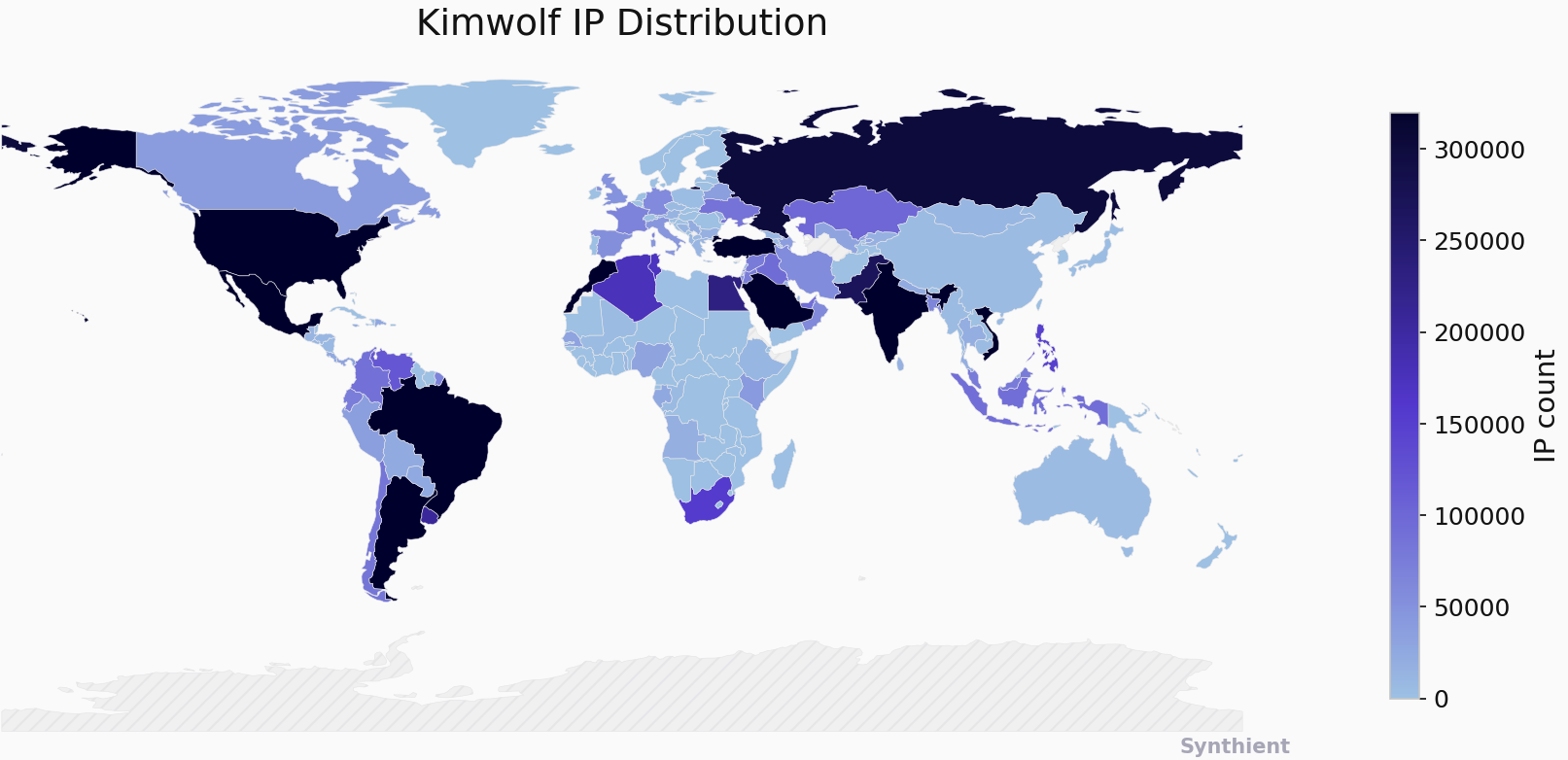

Our January 2 story featured research from the proxy-tracking firm Synthient, which alerted 11 different residential proxy providers that their proxy endpoints were vulnerable to being abused for this kind of local network probing and exploitation.

Most of those vulnerable proxy providers have since taken steps to prevent customers from going upstream into the local networks of residential proxy endpoints, and it appeared that Kimwolf would no longer be able to quickly spread to millions of devices simply by exploiting some residential proxy provider.

However, the source of that Badbox 2.0 screenshot said the Kimwolf botmasters had an ace up their sleeve the whole time: Secret access to the Badbox 2.0 botnet control panel.

“Dort has gotten unauthorized access,” the source said. “So, what happened is normal proxy providers patched this. But Badbox doesn’t sell proxies by itself, so it’s not patched. And as long as Dort has access to Badbox, they would be able to load” the Kimwolf malware directly onto TV boxes associated with Badbox 2.0.

The source said it isn’t clear how Dort gained access to the Badbox botnet panel. But it’s unlikely that Dort’s existing account will persist for much longer: All of our notifications to the qq.com email addresses listed in the control panel screenshot received a copy of that image, as well as questions about the apparently rogue ABCD account.

A new Internet-of-Things (IoT) botnet called Kimwolf has spread to more than 2 million devices, forcing infected systems to participate in massive distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and to relay other malicious and abusive Internet traffic. Kimwolf’s ability to scan the local networks of compromised systems for other IoT devices to infect makes it a sobering threat to organizations, and new research reveals Kimwolf is surprisingly prevalent in government and corporate networks.

Image: Shutterstock, @Elzicon.

Kimwolf grew rapidly in the waning months of 2025 by tricking various “residential proxy” services into relaying malicious commands to devices on the local networks of those proxy endpoints. Residential proxies are sold as a way to anonymize and localize one’s Web traffic to a specific region, and the biggest of these services allow customers to route their Internet activity through devices in virtually any country or city around the globe.

The malware that turns one’s Internet connection into a proxy node is often quietly bundled with various mobile apps and games, and it typically forces the infected device to relay malicious and abusive traffic — including ad fraud, account takeover attempts, and mass content-scraping.

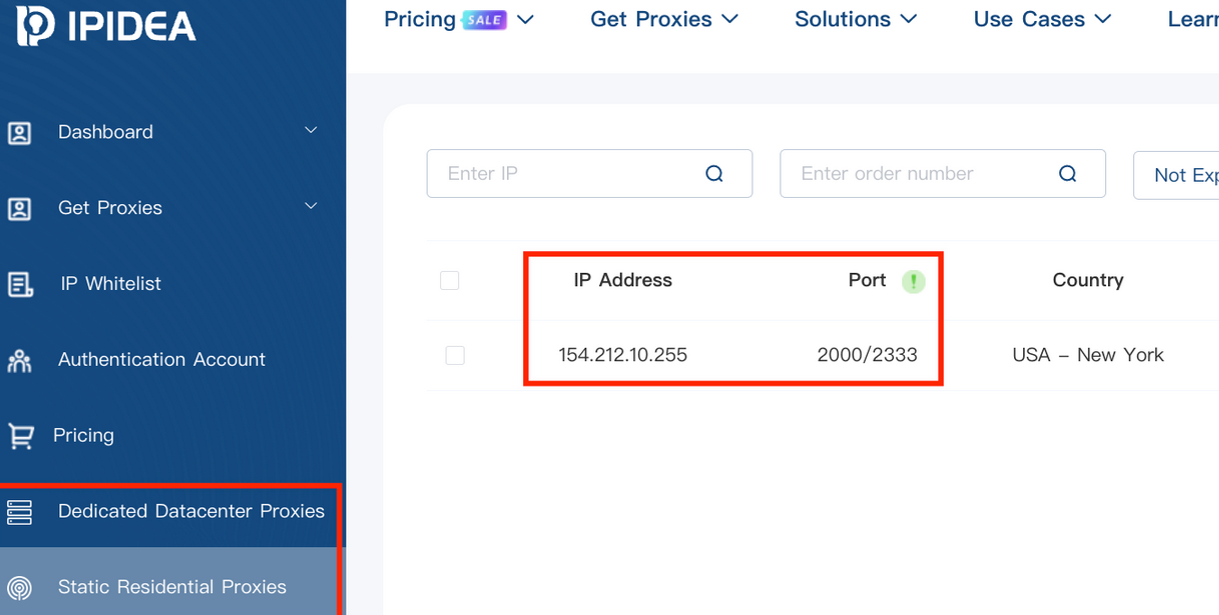

Kimwolf mainly targeted proxies from IPIDEA, a Chinese service that has millions of proxy endpoints for rent on any given week. The Kimwolf operators discovered they could forward malicious commands to the internal networks of IPIDEA proxy endpoints, and then programmatically scan for and infect other vulnerable devices on each endpoint’s local network.

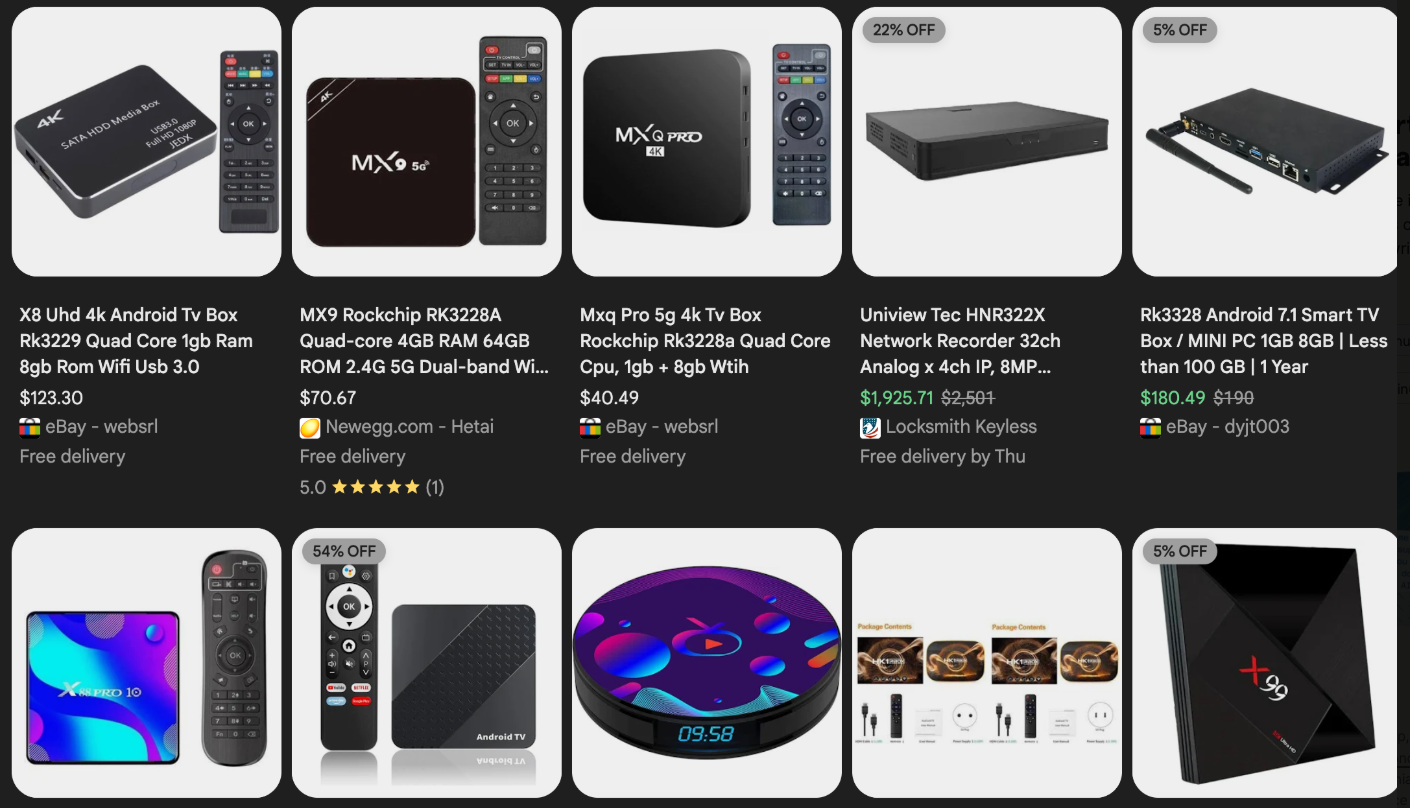

Most of the systems compromised through Kimwolf’s local network scanning have been unofficial Android TV streaming boxes. These are typically Android Open Source Project devices — not Android TV OS devices or Play Protect certified Android devices — and they are generally marketed as a way to watch unlimited (read:pirated) video content from popular subscription streaming services for a one-time fee.

However, a great many of these TV boxes ship to consumers with residential proxy software pre-installed. What’s more, they have no real security or authentication built-in: If you can communicate directly with the TV box, you can also easily compromise it with malware.

While IPIDEA and other affected proxy providers recently have taken steps to block threats like Kimwolf from going upstream into their endpoints (reportedly with varying degrees of success), the Kimwolf malware remains on millions of infected devices.

A screenshot of IPIDEA’s proxy service.

Kimwolf’s close association with residential proxy networks and compromised Android TV boxes might suggest we’d find relatively few infections on corporate networks. However, the security firm Infoblox said a recent review of its customer traffic found nearly 25 percent of them made a query to a Kimwolf-related domain name since October 1, 2025, when the botnet first showed signs of life.

Infoblox found the affected customers are based all over the world and in a wide range of industry verticals, from education and healthcare to government and finance.

“To be clear, this suggests that nearly 25% of customers had at least one device that was an endpoint in a residential proxy service targeted by Kimwolf operators,” Infoblox explained. “Such a device, maybe a phone or a laptop, was essentially co-opted by the threat actor to probe the local network for vulnerable devices. A query means a scan was made, not that new devices were compromised. Lateral movement would fail if there were no vulnerable devices to be found or if the DNS resolution was blocked.”

Synthient, a startup that tracks proxy services and was the first to disclose on January 2 the unique methods Kimwolf uses to spread, found proxy endpoints from IPIDEA were present in alarming numbers at government and academic institutions worldwide. Synthient said it spied at least 33,000 affected Internet addresses at universities and colleges, and nearly 8,000 IPIDEA proxies within various U.S. and foreign government networks.

The top 50 domain names sought out by users of IPIDEA’s residential proxy service, according to Synthient.

In a webinar on January 16, experts at the proxy tracking service Spur profiled Internet addresses associated with IPIDEA and 10 other proxy services that were thought to be vulnerable to Kimwolf’s tricks. Spur found residential proxies in nearly 300 government owned and operated networks, 318 utility companies, 166 healthcare companies or hospitals, and 141 companies in banking and finance.

“I looked at the 298 [government] owned and operated [networks], and so many of them were DoD [U.S. Department of Defense], which is kind of terrifying that DoD has IPIDEA and these other proxy services located inside of it,” Spur Co-Founder Riley Kilmer said. “I don’t know how these enterprises have these networks set up. It could be that [infected devices] are segregated on the network, that even if you had local access it doesn’t really mean much. However, it’s something to be aware of. If a device goes in, anything that device has access to the proxy would have access to.”

Kilmer said Kimwolf demonstrates how a single residential proxy infection can quickly lead to bigger problems for organizations that are harboring unsecured devices behind their firewalls, noting that proxy services present a potentially simple way for attackers to probe other devices on the local network of a targeted organization.

“If you know you have [proxy] infections that are located in a company, you can chose that [network] to come out of and then locally pivot,” Kilmer said. “If you have an idea of where to start or look, now you have a foothold in a company or an enterprise based on just that.”

This is the third story in our series on the Kimwolf botnet. Next week, we’ll shed light on the myriad China-based individuals and companies connected to the Badbox 2.0 botnet, the collective name given to a vast number of Android TV streaming box models that ship with no discernible security or authentication built-in, and with residential proxy malware pre-installed.

Further reading:

The Kimwolf Botnet is Stalking Your Local Network

Who Benefitted from the Aisuru and Kimwolf Botnets?

A Broken System Fueling Botnets (Synthient).

The story you are reading is a series of scoops nestled inside a far more urgent Internet-wide security advisory. The vulnerability at issue has been exploited for months already, and it’s time for a broader awareness of the threat. The short version is that everything you thought you knew about the security of the internal network behind your Internet router probably is now dangerously out of date.

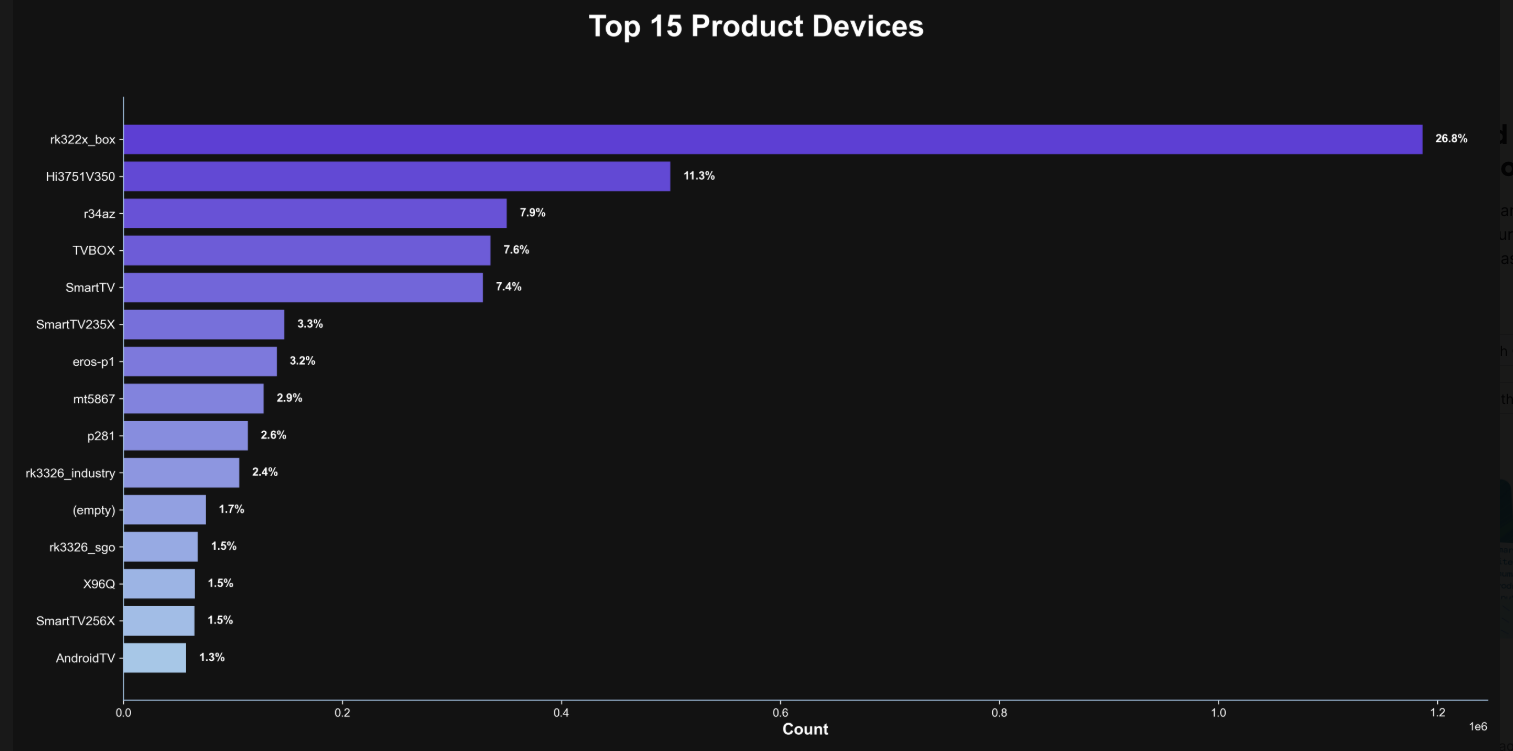

The security company Synthient currently sees more than 2 million infected Kimwolf devices distributed globally but with concentrations in Vietnam, Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the United States. Synthient found that two-thirds of the Kimwolf infections are Android TV boxes with no security or authentication built in.

The past few months have witnessed the explosive growth of a new botnet dubbed Kimwolf, which experts say has infected more than 2 million devices globally. The Kimwolf malware forces compromised systems to relay malicious and abusive Internet traffic — such as ad fraud, account takeover attempts and mass content scraping — and participate in crippling distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks capable of knocking nearly any website offline for days at a time.

More important than Kimwolf’s staggering size, however, is the diabolical method it uses to spread so quickly: By effectively tunneling back through various “residential proxy” networks and into the local networks of the proxy endpoints, and by further infecting devices that are hidden behind the assumed protection of the user’s firewall and Internet router.

Residential proxy networks are sold as a way for customers to anonymize and localize their Web traffic to a specific region, and the biggest of these services allow customers to route their traffic through devices in virtually any country or city around the globe.

The malware that turns an end-user’s Internet connection into a proxy node is often bundled with dodgy mobile apps and games. These residential proxy programs also are commonly installed via unofficial Android TV boxes sold by third-party merchants on popular e-commerce sites like Amazon, BestBuy, Newegg, and Walmart.

These TV boxes range in price from $40 to $400, are marketed under a dizzying range of no-name brands and model numbers, and frequently are advertised as a way to stream certain types of subscription video content for free. But there’s a hidden cost to this transaction: As we’ll explore in a moment, these TV boxes make up a considerable chunk of the estimated two million systems currently infected with Kimwolf.

Some of the unsanctioned Android TV boxes that come with residential proxy malware pre-installed. Image: Synthient.

Kimwolf also is quite good at infecting a range of Internet-connected digital photo frames that likewise are abundant at major e-commerce websites. In November 2025, researchers from Quokka published a report (PDF) detailing serious security issues in Android-based digital picture frames running the Uhale app — including Amazon’s bestselling digital frame as of March 2025.

There are two major security problems with these photo frames and unofficial Android TV boxes. The first is that a considerable percentage of them come with malware pre-installed, or else require the user to download an unofficial Android App Store and malware in order to use the device for its stated purpose (video content piracy). The most typical of these uninvited guests are small programs that turn the device into a residential proxy node that is resold to others.

The second big security nightmare with these photo frames and unsanctioned Android TV boxes is that they rely on a handful of Internet-connected microcomputer boards that have no discernible security or authentication requirements built-in. In other words, if you are on the same network as one or more of these devices, you can likely compromise them simultaneously by issuing a single command across the network.

The combination of these two security realities came to the fore in October 2025, when an undergraduate computer science student at the Rochester Institute of Technology began closely tracking Kimwolf’s growth, and interacting directly with its apparent creators on a daily basis.

Benjamin Brundage is the 22-year-old founder of the security firm Synthient, a startup that helps companies detect proxy networks and learn how those networks are being abused. Conducting much of his research into Kimwolf while studying for final exams, Brundage told KrebsOnSecurity in late October 2025 he suspected Kimwolf was a new Android-based variant of Aisuru, a botnet that was incorrectly blamed for a number of record-smashing DDoS attacks last fall.

Brundage says Kimwolf grew rapidly by abusing a glaring vulnerability in many of the world’s largest residential proxy services. The crux of the weakness, he explained, was that these proxy services weren’t doing enough to prevent their customers from forwarding requests to internal servers of the individual proxy endpoints.

Most proxy services take basic steps to prevent their paying customers from “going upstream” into the local network of proxy endpoints, by explicitly denying requests for local addresses specified in RFC-1918, including the well-known Network Address Translation (NAT) ranges 10.0.0.0/8, 192.168.0.0/16, and 172.16.0.0/12. These ranges allow multiple devices in a private network to access the Internet using a single public IP address, and if you run any kind of home or office network, your internal address space operates within one or more of these NAT ranges.

However, Brundage discovered that the people operating Kimwolf had figured out how to talk directly to devices on the internal networks of millions of residential proxy endpoints, simply by changing their Domain Name System (DNS) settings to match those in the RFC-1918 address ranges.

“It is possible to circumvent existing domain restrictions by using DNS records that point to 192.168.0.1 or 0.0.0.0,” Brundage wrote in a first-of-its-kind security advisory sent to nearly a dozen residential proxy providers in mid-December 2025. “This grants an attacker the ability to send carefully crafted requests to the current device or a device on the local network. This is actively being exploited, with attackers leveraging this functionality to drop malware.”

As with the digital photo frames mentioned above, many of these residential proxy services run solely on mobile devices that are running some game, VPN or other app with a hidden component that turns the user’s mobile phone into a residential proxy — often without any meaningful consent.

In a report published today, Synthient said key actors involved in Kimwolf were observed monetizing the botnet through app installs, selling residential proxy bandwidth, and selling its DDoS functionality.

“Synthient expects to observe a growing interest among threat actors in gaining unrestricted access to proxy networks to infect devices, obtain network access, or access sensitive information,” the report observed. “Kimwolf highlights the risks posed by unsecured proxy networks and their viability as an attack vector.”

After purchasing a number of unofficial Android TV box models that were most heavily represented in the Kimwolf botnet, Brundage further discovered the proxy service vulnerability was only part of the reason for Kimwolf’s rapid rise: He also found virtually all of the devices he tested were shipped from the factory with a powerful feature called Android Debug Bridge (ADB) mode enabled by default.

Many of the unofficial Android TV boxes infected by Kimwolf include the ominous disclaimer: “Made in China. Overseas use only.” Image: Synthient.

ADB is a diagnostic tool intended for use solely during the manufacturing and testing processes, because it allows the devices to be remotely configured and even updated with new (and potentially malicious) firmware. However, shipping these devices with ADB turned on creates a security nightmare because in this state they constantly listen for and accept unauthenticated connection requests.

For example, opening a command prompt and typing “adb connect” along with a vulnerable device’s (local) IP address followed immediately by “:5555” will very quickly offer unrestricted “super user” administrative access.

Brundage said by early December, he’d identified a one-to-one overlap between new Kimwolf infections and proxy IP addresses offered for rent by China-based IPIDEA, currently the world’s largest residential proxy network by all accounts.

“Kimwolf has almost doubled in size this past week, just by exploiting IPIDEA’s proxy pool,” Brundage told KrebsOnSecurity in early December as he was preparing to notify IPIDEA and 10 other proxy providers about his research.

Brundage said Synthient first confirmed on December 1, 2025 that the Kimwolf botnet operators were tunneling back through IPIDEA’s proxy network and into the local networks of systems running IPIDEA’s proxy software. The attackers dropped the malware payload by directing infected systems to visit a specific Internet address and to call out the pass phrase “krebsfiveheadindustries” in order to unlock the malicious download.

On December 30, Synthient said it was tracking roughly 2 million IPIDEA addresses exploited by Kimwolf in the previous week. Brundage said he has witnessed Kimwolf rebuilding itself after one recent takedown effort targeting its control servers — from almost nothing to two million infected systems just by tunneling through proxy endpoints on IPIDEA for a couple of days.

Brundage said IPIDEA has a seemingly inexhaustible supply of new proxies, advertising access to more than 100 million residential proxy endpoints around the globe in the past week alone. Analyzing the exposed devices that were part of IPIDEA’s proxy pool, Synthient said it found more than two-thirds were Android devices that could be compromised with no authentication needed.

After charting a tight overlap in Kimwolf-infected IP addresses and those sold by IPIDEA, Brundage was eager to make his findings public: The vulnerability had clearly been exploited for several months, although it appeared that only a handful of cybercrime actors were aware of the capability. But he also knew that going public without giving vulnerable proxy providers an opportunity to understand and patch it would only lead to more mass abuse of these services by additional cybercriminal groups.

On December 17, Brundage sent a security notification to all 11 of the apparently affected proxy providers, hoping to give each at least a few weeks to acknowledge and address the core problems identified in his report before he went public. Many proxy providers who received the notification were resellers of IPIDEA that white-labeled the company’s service.

KrebsOnSecurity first sought comment from IPIDEA in October 2025, in reporting on a story about how the proxy network appeared to have benefitted from the rise of the Aisuru botnet, whose administrators appeared to shift from using the botnet primarily for DDoS attacks to simply installing IPIDEA’s proxy program, among others.

On December 25, KrebsOnSecurity received an email from an IPIDEA employee identified only as “Oliver,” who said allegations that IPIDEA had benefitted from Aisuru’s rise were baseless.

“After comprehensively verifying IP traceability records and supplier cooperation agreements, we found no association between any of our IP resources and the Aisuru botnet, nor have we received any notifications from authoritative institutions regarding our IPs being involved in malicious activities,” Oliver wrote. “In addition, for external cooperation, we implement a three-level review mechanism for suppliers, covering qualification verification, resource legality authentication and continuous dynamic monitoring, to ensure no compliance risks throughout the entire cooperation process.”

“IPIDEA firmly opposes all forms of unfair competition and malicious smearing in the industry, always participates in market competition with compliant operation and honest cooperation, and also calls on the entire industry to jointly abandon irregular and unethical behaviors and build a clean and fair market ecosystem,” Oliver continued.

Meanwhile, the same day that Oliver’s email arrived, Brundage shared a response he’d just received from IPIDEA’s security officer, who identified himself only by the first name Byron. The security officer said IPIDEA had made a number of important security changes to its residential proxy service to address the vulnerability identified in Brundage’s report.

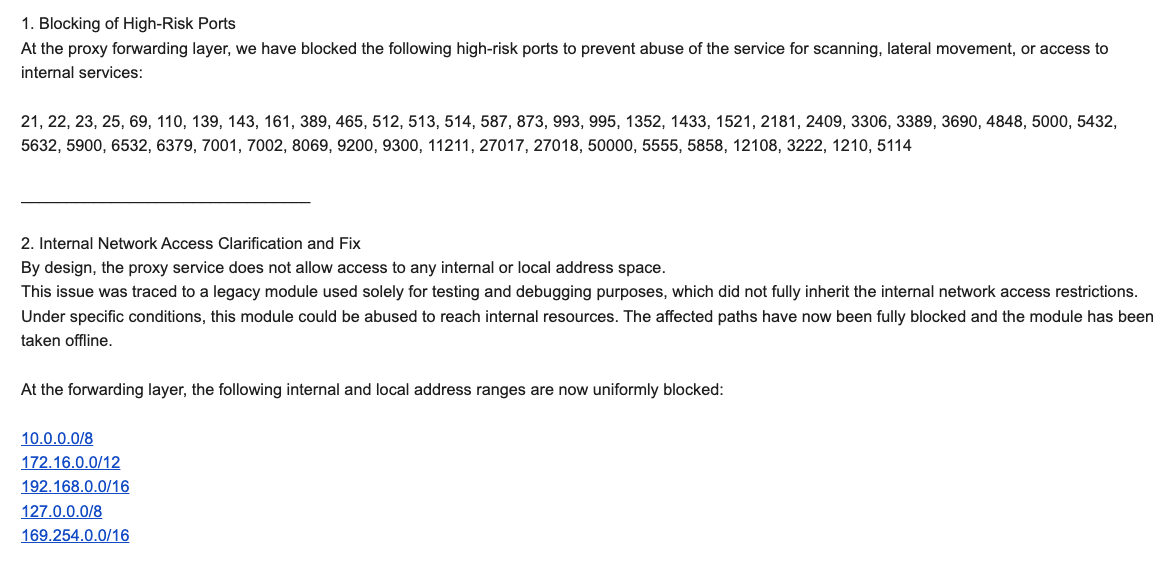

“By design, the proxy service does not allow access to any internal or local address space,” Byron explained. “This issue was traced to a legacy module used solely for testing and debugging purposes, which did not fully inherit the internal network access restrictions. Under specific conditions, this module could be abused to reach internal resources. The affected paths have now been fully blocked and the module has been taken offline.”

Byron told Brundage IPIDEA also instituted multiple mitigations for blocking DNS resolution to internal (NAT) IP ranges, and that it was now blocking proxy endpoints from forwarding traffic on “high-risk” ports “to prevent abuse of the service for scanning, lateral movement, or access to internal services.”

An excerpt from an email sent by IPIDEA’s security officer in response to Brundage’s vulnerability notification. Click to enlarge.

Brundage said IPIDEA appears to have successfully patched the vulnerabilities he identified. He also noted he never observed the Kimwolf actors targeting proxy services other than IPIDEA, which has not responded to requests for comment.

Riley Kilmer is founder of Spur.us, a technology firm that helps companies identify and filter out proxy traffic. Kilmer said Spur has tested Brundage’s findings and confirmed that IPIDEA and all of its affiliate resellers indeed allowed full and unfiltered access to the local LAN.

Kilmer said one model of unsanctioned Android TV boxes that is especially popular — the Superbox, which we profiled in November’s Is Your Android TV Streaming Box Part of a Botnet? — leaves Android Debug Mode running on localhost:5555.

“And since Superbox turns the IP into an IPIDEA proxy, a bad actor just has to use the proxy to localhost on that port and install whatever bad SDKs [software development kits] they want,” Kilmer told KrebsOnSecurity.

Superbox media streaming boxes for sale on Walmart.com.

Both Brundage and Kilmer say IPIDEA appears to be the second or third reincarnation of a residential proxy network formerly known as 911S5 Proxy, a service that operated between 2014 and 2022 and was wildly popular on cybercrime forums. 911S5 Proxy imploded a week after KrebsOnSecurity published a deep dive on the service’s sketchy origins and leadership in China.

In that 2022 profile, we cited work by researchers at the University of Sherbrooke in Canada who were studying the threat 911S5 could pose to internal corporate networks. The researchers noted that “the infection of a node enables the 911S5 user to access shared resources on the network such as local intranet portals or other services.”

“It also enables the end user to probe the LAN network of the infected node,” the researchers explained. “Using the internal router, it would be possible to poison the DNS cache of the LAN router of the infected node, enabling further attacks.”

911S5 initially responded to our reporting in 2022 by claiming it was conducting a top-down security review of the service. But the proxy service abruptly closed up shop just one week later, saying a malicious hacker had destroyed all of the company’s customer and payment records. In July 2024, The U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned the alleged creators of 911S5, and the U.S. Department of Justice arrested the Chinese national named in my 2022 profile of the proxy service.

Kilmer said IPIDEA also operates a sister service called 922 Proxy, which the company has pitched from Day One as a seamless alternative to 911S5 Proxy.

“You cannot tell me they don’t want the 911 customers by calling it that,” Kilmer said.

Among the recipients of Synthient’s notification was the proxy giant Oxylabs. Brundage shared an email he received from Oxylabs’ security team on December 31, which acknowledged Oxylabs had started rolling out security modifications to address the vulnerabilities described in Synthient’s report.

Reached for comment, Oxylabs confirmed they “have implemented changes that now eliminate the ability to bypass the blocklist and forward requests to private network addresses using a controlled domain.” But it said there is no evidence that Kimwolf or other other attackers exploited its network.

“In parallel, we reviewed the domains identified in the reported exploitation activity and did not observe traffic associated with them,” the Oxylabs statement continued. “Based on this review, there is no indication that our residential network was impacted by these activities.”

Consider the following scenario, in which the mere act of allowing someone to use your Wi-Fi network could lead to a Kimwolf botnet infection. In this example, a friend or family member comes to stay with you for a few days, and you grant them access to your Wi-Fi without knowing that their mobile phone is infected with an app that turns the device into a residential proxy node. At that point, your home’s public IP address will show up for rent at the website of some residential proxy provider.

Miscreants like those behind Kimwolf then use residential proxy services online to access that proxy node on your IP, tunnel back through it and into your local area network (LAN), and automatically scan the internal network for devices with Android Debug Bridge mode turned on.

By the time your guest has packed up their things, said their goodbyes and disconnected from your Wi-Fi, you now have two devices on your local network — a digital photo frame and an unsanctioned Android TV box — that are infected with Kimwolf. You may have never intended for these devices to be exposed to the larger Internet, and yet there you are.

Here’s another possible nightmare scenario: Attackers use their access to proxy networks to modify your Internet router’s settings so that it relies on malicious DNS servers controlled by the attackers — allowing them to control where your Web browser goes when it requests a website. Think that’s far-fetched? Recall the DNSChanger malware from 2012 that infected more than a half-million routers with search-hijacking malware, and ultimately spawned an entire security industry working group focused on containing and eradicating it.

Much of what is published so far on Kimwolf has come from the Chinese security firm XLab, which was the first to chronicle the rise of the Aisuru botnet in late 2024. In its latest blog post, XLab said it began tracking Kimwolf on October 24, when the botnet’s control servers were swamping Cloudflare’s DNS servers with lookups for the distinctive domain 14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132[.]su.

This domain and others connected to early Kimwolf variants spent several weeks topping Cloudflare’s chart of the Internet’s most sought-after domains, edging out Google.com and Apple.com of their rightful spots in the top 5 most-requested domains. That’s because during that time Kimwolf was asking its millions of bots to check in frequently using Cloudflare’s DNS servers.

The Chinese security firm XLab found the Kimwolf botnet had enslaved between 1.8 and 2 million devices, with heavy concentrations in Brazil, India, The United States of America and Argentina. Image: blog.xLab.qianxin.com

It is clear from reading the XLab report that KrebsOnSecurity (and security experts) probably erred in misattributing some of Kimwolf’s early activities to the Aisuru botnet, which appears to be operated by a different group entirely. IPDEA may have been truthful when it said it had no affiliation with the Aisuru botnet, but Brundage’s data left no doubt that its proxy service clearly was being massively abused by Aisuru’s Android variant, Kimwolf.

XLab said Kimwolf has infected at least 1.8 million devices, and has shown it is able to rebuild itself quickly from scratch.

“Analysis indicates that Kimwolf’s primary infection targets are TV boxes deployed in residential network environments,” XLab researchers wrote. “Since residential networks usually adopt dynamic IP allocation mechanisms, the public IPs of devices change over time, so the true scale of infected devices cannot be accurately measured solely by the quantity of IPs. In other words, the cumulative observation of 2.7 million IP addresses does not equate to 2.7 million infected devices.”

XLab said measuring Kimwolf’s size also is difficult because infected devices are distributed across multiple global time zones. “Affected by time zone differences and usage habits (e.g., turning off devices at night, not using TV boxes during holidays, etc.), these devices are not online simultaneously, further increasing the difficulty of comprehensive observation through a single time window,” the blog post observed.

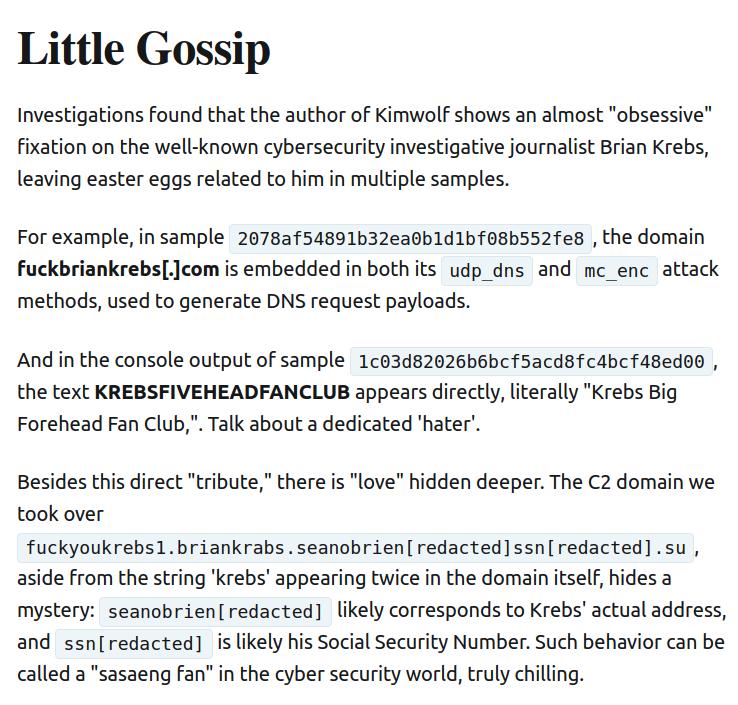

XLab noted that the Kimwolf author shows an almost ‘obsessive’ fixation” on Yours Truly, apparently leaving “easter eggs” related to my name in multiple places through the botnet’s code and communications:

Image: XLAB.

One frustrating aspect of threats like Kimwolf is that in most cases it is not easy for the average user to determine if there are any devices on their internal network which may be vulnerable to threats like Kimwolf and/or already infected with residential proxy malware.

Let’s assume that through years of security training or some dark magic you can successfully identify that residential proxy activity on your internal network was linked to a specific mobile device inside your house: From there, you’d still need to isolate and remove the app or unwanted component that is turning the device into a residential proxy.

Also, the tooling and knowledge needed to achieve this kind of visibility just isn’t there from an average consumer standpoint. The work that it takes to configure your network so you can see and interpret logs of all traffic coming in and out is largely beyond the skillset of most Internet users (and, I’d wager, many security experts). But it’s a topic worth exploring in an upcoming story.

Happily, Synthient has erected a page on its website that will state whether a visitor’s public Internet address was seen among those of Kimwolf-infected systems. Brundage also has compiled a list of the unofficial Android TV boxes that are most highly represented in the Kimwolf botnet.

If you own a TV box that matches one of these model names and/or numbers, please just rip it out of your network. If you encounter one of these devices on the network of a family member or friend, send them a link to this story and explain that it’s not worth the potential hassle and harm created by keeping them plugged in.

The top 15 product devices represented in the Kimwolf botnet, according to Synthient.

Chad Seaman is a principal security researcher with Akamai Technologies. Seaman said he wants more consumers to be wary of these pseudo Android TV boxes to the point where they avoid them altogether.

“I want the consumer to be paranoid of these crappy devices and of these residential proxy schemes,” he said. “We need to highlight why they’re dangerous to everyone and to the individual. The whole security model where people think their LAN (Local Internal Network) is safe, that there aren’t any bad guys on the LAN so it can’t be that dangerous is just really outdated now.”

“The idea that an app can enable this type of abuse on my network and other networks, that should really give you pause,” about which devices to allow onto your local network, Seaman said. “And it’s not just Android devices here. Some of these proxy services have SDKs for Mac and Windows, and the iPhone. It could be running something that inadvertently cracks open your network and lets countless random people inside.”

In July 2025, Google filed a “John Doe” lawsuit (PDF) against 25 unidentified defendants collectively dubbed the “BadBox 2.0 Enterprise,” which Google described as a botnet of over ten million unsanctioned Android streaming devices engaged in advertising fraud. Google said the BADBOX 2.0 botnet, in addition to compromising multiple types of devices prior to purchase, also can infect devices by requiring the download of malicious apps from unofficial marketplaces.

Google’s lawsuit came on the heels of a June 2025 advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which warned that cyber criminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by either configuring the products with malware prior to the user’s purchase, or infecting the device as it downloads required applications that contain backdoors — usually during the set-up process.

The FBI said BADBOX 2.0 was discovered after the original BADBOX campaign was disrupted in 2024. The original BADBOX was identified in 2023, and primarily consisted of Android operating system devices that were compromised with backdoor malware prior to purchase.

Lindsay Kaye is vice president of threat intelligence at HUMAN Security, a company that worked closely on the BADBOX investigations. Kaye said the BADBOX botnets and the residential proxy networks that rode on top of compromised devices were detected because they enabled a ridiculous amount of advertising fraud, as well as ticket scalping, retail fraud, account takeovers and content scraping.

Kaye said consumers should stick to known brands when it comes to purchasing things that require a wired or wireless connection.

“If people are asking what they can do to avoid being victimized by proxies, it’s safest to stick with name brands,” Kaye said. “Anything promising something for free or low-cost, or giving you something for nothing just isn’t worth it. And be careful about what apps you allow on your phone.”

Many wireless routers these days make it relatively easy to deploy a “Guest” wireless network on-the-fly. Doing so allows your guests to browse the Internet just fine but it blocks their device from being able to talk to other devices on the local network — such as shared folders, printers and drives. If someone — a friend, family member, or contractor — requests access to your network, give them the guest Wi-Fi network credentials if you have that option.

There is a small but vocal pro-piracy camp that is almost condescendingly dismissive of the security threats posed by these unsanctioned Android TV boxes. These tech purists positively chafe at the idea of people wholesale discarding one of these TV boxes. A common refrain from this camp is that Internet-connected devices are not inherently bad or good, and that even factory-infected boxes can be flashed with new firmware or custom ROMs that contain no known dodgy software.

However, it’s important to point out that the majority of people buying these devices are not security or hardware experts; the devices are sought out because they dangle something of value for “free.” Most buyers have no idea of the bargain they’re making when plugging one of these dodgy TV boxes into their network.

It is somewhat remarkable that we haven’t yet seen the entertainment industry applying more visible pressure on the major e-commerce vendors to stop peddling this insecure and actively malicious hardware that is largely made and marketed for video piracy. These TV boxes are a public nuisance for bundling malicious software while having no apparent security or authentication built-in, and these two qualities make them an attractive nuisance for cybercriminals.

Stay tuned for Part II in this series, which will poke through clues left behind by the people who appear to have built Kimwolf and benefited from it the most.

On the surface, the Superbox media streaming devices for sale at retailers like BestBuy and Walmart may seem like a steal: They offer unlimited access to more than 2,200 pay-per-view and streaming services like Netflix, ESPN and Hulu, all for a one-time fee of around $400. But security experts warn these TV boxes require intrusive software that forces the user’s network to relay Internet traffic for others, traffic that is often tied to cybercrime activity such as advertising fraud and account takeovers.

Superbox media streaming boxes for sale on Walmart.com.

Superbox bills itself as an affordable way for households to stream all of the television and movie content they could possibly want, without the hassle of monthly subscription fees — for a one-time payment of nearly $400.

“Tired of confusing cable bills and hidden fees?,” Superbox’s website asks in a recent blog post titled, “Cheap Cable TV for Low Income: Watch TV, No Monthly Bills.”

“Real cheap cable TV for low income solutions does exist,” the blog continues. “This guide breaks down the best alternatives to stop overpaying, from free over-the-air options to one-time purchase devices that eliminate monthly bills.”

Superbox claims that watching a stream of movies, TV shows, and sporting events won’t violate U.S. copyright law.

“SuperBox is just like any other Android TV box on the market, we can not control what software customers will use,” the company’s website maintains. “And you won’t encounter a law issue unless uploading, downloading, or broadcasting content to a large group.”

A blog post from the Superbox website.

There is nothing illegal about the sale or use of the Superbox itself, which can be used strictly as a way to stream content at providers where users already have a paid subscription. But that is not why people are shelling out $400 for these machines. The only way to watch those 2,200+ channels for free with a Superbox is to install several apps made for the device that enable them to stream this content.

Superbox’s homepage includes a prominent message stating the company does “not sell access to or preinstall any apps that bypass paywalls or provide access to unauthorized content.” The company explains that they merely provide the hardware, while customers choose which apps to install.

“We only sell the hardware device,” the notice states. “Customers must use official apps and licensed services; unauthorized use may violate copyright law.”

Superbox is technically correct here, except for maybe the part about how customers must use official apps and licensed services: Before the Superbox can stream those thousands of channels, users must configure the device to update itself, and the first step involves ripping out Google’s official Play store and replacing it with something called the “App Store” or “Blue TV Store.”

Superbox does this because the device does not use the official Google-certified Android TV system, and its apps will not load otherwise. Only after the Google Play store has been supplanted by this unofficial App Store do the various movie and video streaming apps that are built specifically for the Superbox appear available for download (again, outside of Google’s app ecosystem).

Experts say while these Android streaming boxes generally do what they advertise — enabling buyers to stream video content that would normally require a paid subscription — the apps that enable the streaming also ensnare the user’s Internet connection in a distributed residential proxy network that uses the devices to relay traffic from others.

Ashley is a senior solutions engineer at Censys, a cyber intelligence company that indexes Internet-connected devices, services and hosts. Ashley requested that only her first name be used in this story.

In a recent video interview, Ashley showed off several Superbox models that Censys was studying in the malware lab — including one purchased off the shelf at BestBuy.

“I’m sure a lot of people are thinking, ‘Hey, how bad could it be if it’s for sale at the big box stores?'” she said. “But the more I looked, things got weirder and weirder.”

Ashley said she found the Superbox devices immediately contacted a server at the Chinese instant messaging service Tencent QQ, as well as a residential proxy service called Grass IO.

Also known as getgrass[.]io, Grass says it is “a decentralized network that allows users to earn rewards by sharing their unused Internet bandwidth with AI labs and other companies.”

“Buyers seek unused internet bandwidth to access a more diverse range of IP addresses, which enables them to see certain websites from a retail perspective,” the Grass website explains. “By utilizing your unused internet bandwidth, they can conduct market research, or perform tasks like web scraping to train AI.”

Reached via Twitter/X, Grass founder Andrej Radonjic told KrebsOnSecurity he’d never heard of a Superbox, and that Grass has no affiliation with the device maker.

“It looks like these boxes are distributing an unethical proxy network which people are using to try to take advantage of Grass,” Radonjic said. “The point of grass is to be an opt-in network. You download the grass app to monetize your unused bandwidth. There are tons of sketchy SDKs out there that hijack people’s bandwidth to help webscraping companies.”

Radonjic said Grass has implemented “a robust system to identify network abusers,” and that if it discovers anyone trying to misuse or circumvent its terms of service, the company takes steps to stop it and prevent those users from earning points or rewards.

Superbox’s parent company, Super Media Technology Company Ltd., lists its street address as a UPS store in Fountain Valley, Calif. The company did not respond to multiple inquiries.

According to this teardown by behindmlm.com, a blog that covers multi-level marketing (MLM) schemes, Grass’s compensation plan is built around “grass points,” which are earned through the use of the Grass app and through app usage by recruited affiliates. Affiliates can earn 5,000 grass points for clocking 100 hours usage of Grass’s app, but they must progress through ten affiliate tiers or ranks before they can redeem their grass points (presumably for some type of cryptocurrency). The 10th or “Titan” tier requires affiliates to accumulate a whopping 50 million grass points, or recruit at least 221 more affiliates.

Radonjic said Grass’s system has changed in recent months, and confirmed the company has a referral program where users can earn Grass Uptime Points by contributing their own bandwidth and/or by inviting other users to participate.

“Users are not required to participate in the referral program to earn Grass Uptime Points or to receive Grass Tokens,” Radonjic said. “Grass is in the process of phasing out the referral program and has introduced an updated Grass Points model.”

A review of the Terms and Conditions page for getgrass[.]io at the Wayback Machine shows Grass’s parent company has changed names at least five times in the course of its two-year existence. Searching the Wayback Machine on getgrass[.]io shows that in June 2023 Grass was owned by a company called Wynd Network. By March 2024, the owner was listed as Lower Tribeca Corp. in the Bahamas. By August 2024, Grass was controlled by a Half Space Labs Limited, and in November 2024 the company was owned by Grass OpCo (BVI) Ltd. Currently, the Grass website says its parent is just Grass OpCo Ltd (no BVI in the name).

Radonjic acknowledged that Grass has undergone “a handful of corporate clean-ups over the last couple of years,” but described them as administrative changes that had no operational impact. “These reflect normal early-stage restructuring as the project moved from initial development…into the current structure under the Grass Foundation,” he said.

Censys’s Ashley said the phone home to China’s Tencent QQ instant messaging service was the first red flag with the Superbox devices she examined. She also discovered the streaming boxes included powerful network analysis and remote access tools, such as Tcpdump and Netcat.

“This thing DNS hijacked my router, did ARP poisoning to the point where things fall off the network so they can assume that IP, and attempted to bypass controls,” she said. “I have root on all of them now, and they actually have a folder called ‘secondstage.’ These devices also have Netcat and Tcpdump on them, and yet they are supposed to be streaming devices.”

A quick online search shows various Superbox models and many similar Android streaming devices for sale at a wide range of top retail destinations, including Amazon, BestBuy, Newegg, and Walmart. Newegg.com, for example, currently lists more than three dozen Superbox models. In all cases, the products are sold by third-party merchants on these platforms, but in many instances the fulfillment comes from the e-commerce platform itself.

“Newegg is pretty bad now with these devices,” Ashley said. “Ebay is the funniest, because they have Superbox in Spanish — the SuperCaja — which is very popular.”

Ashley said Amazon recently cracked down on Android streaming devices branded as Superbox, but that those listings can still be found under the more generic title “modem and router combo” (which may be slightly closer to the truth about the device’s behavior).

Superbox doesn’t advertise its products in the conventional sense. Rather, it seems to rely on lesser-known influencers on places like Youtube and TikTok to promote the devices. Meanwhile, Ashley said, Superbox pays those influencers 50 percent of the value of each device they sell.

“It’s weird to me because influencer marketing usually caps compensation at 15 percent, and it means they don’t care about the money,” she said. “This is about building their network.”

A TikTok influencer casually mentions and promotes Superbox while chatting with her followers over a glass of wine.

As plentiful as the Superbox is on e-commerce sites, it is just one brand in an ocean of no-name Android-based TV boxes available to consumers. While these devices generally do provide buyers with “free” streaming content, they also tend to include factory-installed malware or require the installation of third-party apps that engage the user’s Internet address in advertising fraud.

In July 2025, Google filed a “John Doe” lawsuit (PDF) against 25 unidentified defendants dubbed the “BadBox 2.0 Enterprise,” which Google described as a botnet of over ten million Android streaming devices that engaged in advertising fraud. Google said the BADBOX 2.0 botnet, in addition to compromising multiple types of devices prior to purchase, can also infect devices by requiring the download of malicious apps from unofficial marketplaces.

Some of the unofficial Android devices flagged by Google as part of the Badbox 2.0 botnet are still widely for sale at major e-commerce vendors. Image: Google.

Several of the Android streaming devices flagged in Google’s lawsuit are still for sale on top U.S. retail sites. For example, searching for the “X88Pro 10” and the “T95” Android streaming boxes finds both continue to be peddled by Amazon sellers.

Google’s lawsuit came on the heels of a June 2025 advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which warned that cyber criminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by either configuring the products with malicious software prior to the user’s purchase, or infecting the device as it downloads required applications that contain backdoors, usually during the set-up process.

“Once these compromised IoT devices are connected to home networks, the infected devices are susceptible to becoming part of the BADBOX 2.0 botnet and residential proxy services known to be used for malicious activity,” the FBI said.

The FBI said BADBOX 2.0 was discovered after the original BADBOX campaign was disrupted in 2024. The original BADBOX was identified in 2023, and primarily consisted of Android operating system devices that were compromised with backdoor malware prior to purchase.

Riley Kilmer is founder of Spur, a company that tracks residential proxy networks. Kilmer said Badbox 2.0 was used as a distribution platform for IPidea, a China-based entity that is now the world’s largest residential proxy network.

Kilmer and others say IPidea is merely a rebrand of 911S5 Proxy, a China-based proxy provider sanctioned last year by the U.S. Department of the Treasury for operating a botnet that helped criminals steal billions of dollars from financial institutions, credit card issuers, and federal lending programs (the U.S. Department of Justice also arrested the alleged owner of 911S5).

How are most IPidea customers using the proxy service? According to the proxy detection service Synthient, six of the top ten destinations for IPidea proxies involved traffic that has been linked to either ad fraud or credential stuffing (account takeover attempts).

Kilmer said companies like Grass are probably being truthful when they say that some of their customers are companies performing web scraping to train artificial intelligence efforts, because a great deal of content scraping which ultimately benefits AI companies is now leveraging these proxy networks to further obfuscate their aggressive data-slurping activity. By routing this unwelcome traffic through residential IP addresses, Kilmer said, content scraping firms can make it far trickier to filter out.

“Web crawling and scraping has always been a thing, but AI made it like a commodity, data that had to be collected,” Kilmer told KrebsOnSecurity. “Everybody wanted to monetize their own data pots, and how they monetize that is different across the board.”

Products like Superbox are drawing increased interest from consumers as more popular network television shows and sportscasts migrate to subscription streaming services, and as people begin to realize they’re spending as much or more on streaming services than they previously paid for cable or satellite TV.

These streaming devices from no-name technology vendors are another example of the maxim, “If something is free, you are the product,” meaning the company is making money by selling access to and/or information about its users and their data.

Superbox owners might counter, “Free? I paid $400 for that device!” But remember: Just because you paid a lot for something doesn’t mean you are done paying for it, or that somehow you are the only one who might be worse off from the transaction.

It may be that many Superbox customers don’t care if someone uses their Internet connection to tunnel traffic for ad fraud and account takeovers; for them, it beats paying for multiple streaming services each month. My guess, however, is that quite a few people who buy (or are gifted) these products have little understanding of the bargain they’re making when they plug them into an Internet router.

Superbox performs some serious linguistic gymnastics to claim its products don’t violate copyright laws, and that its customers alone are responsible for understanding and observing any local laws on the matter. However, buyer beware: If you’re a resident of the United States, you should know that using these devices for unauthorized streaming violates the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), and can incur legal action, fines, and potential warnings and/or suspension of service by your Internet service provider.

According to the FBI, there are several signs to look for that may indicate a streaming device you own is malicious, including:

-The presence of suspicious marketplaces where apps are downloaded.

-Requiring Google Play Protect settings to be disabled.

-Generic TV streaming devices advertised as unlocked or capable of accessing free content.

-IoT devices advertised from unrecognizable brands.

-Android devices that are not Play Protect certified.

-Unexplained or suspicious Internet traffic.

This explainer from the Electronic Frontier Foundation delves a bit deeper into each of the potential symptoms listed above.