The story you are reading is a series of scoops nestled inside a far more urgent Internet-wide security advisory. The vulnerability at issue has been exploited for months already, and it’s time for a broader awareness of the threat. The short version is that everything you thought you knew about the security of the internal network behind your Internet router probably is now dangerously out of date.

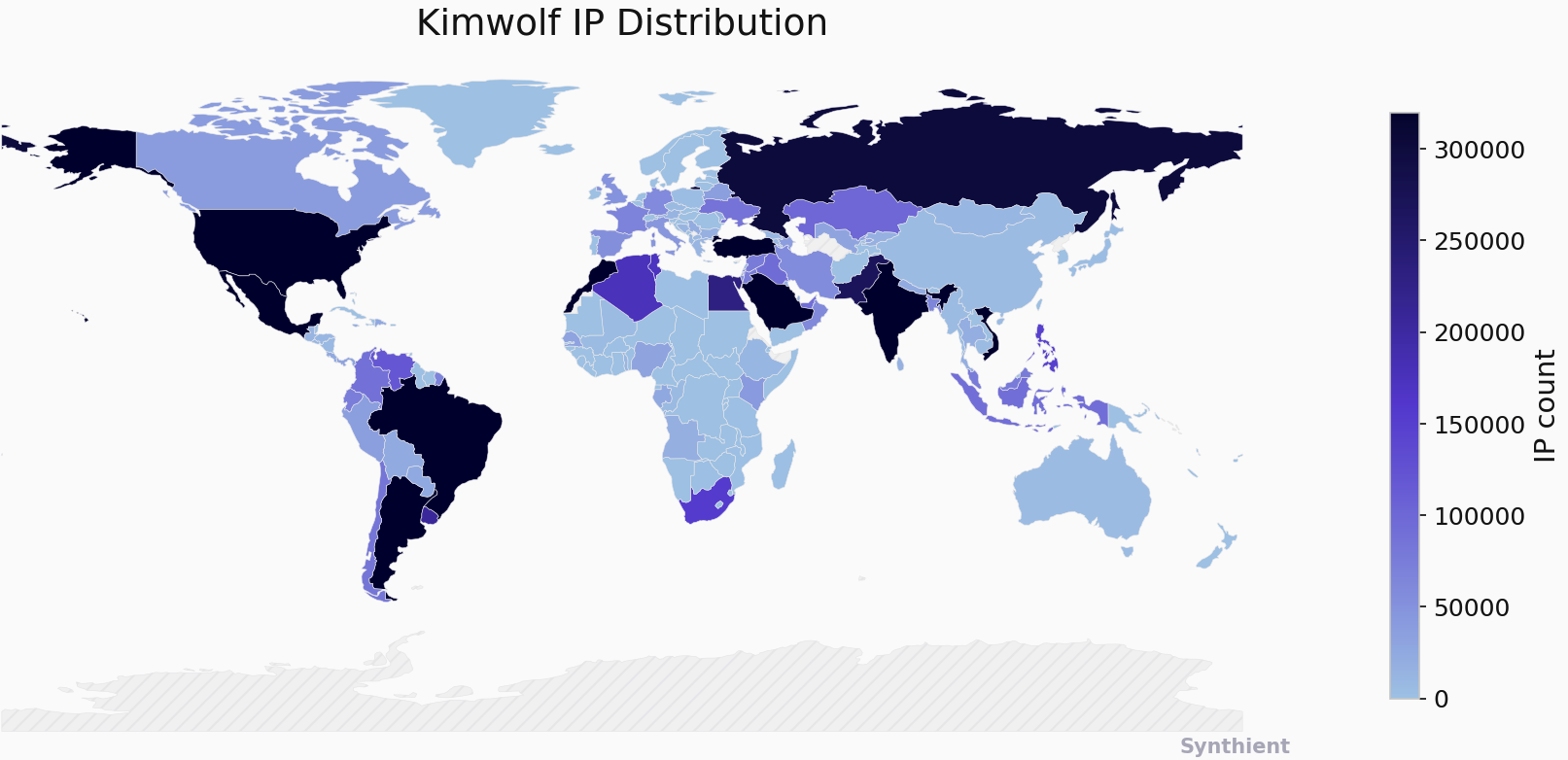

The security company Synthient currently sees more than 2 million infected Kimwolf devices distributed globally but with concentrations in Vietnam, Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, Russia and the United States. Synthient found that two-thirds of the Kimwolf infections are Android TV boxes with no security or authentication built in.

The past few months have witnessed the explosive growth of a new botnet dubbed Kimwolf, which experts say has infected more than 2 million devices globally. The Kimwolf malware forces compromised systems to relay malicious and abusive Internet traffic — such as ad fraud, account takeover attempts and mass content scraping — and participate in crippling distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks capable of knocking nearly any website offline for days at a time.

More important than Kimwolf’s staggering size, however, is the diabolical method it uses to spread so quickly: By effectively tunneling back through various “residential proxy” networks and into the local networks of the proxy endpoints, and by further infecting devices that are hidden behind the assumed protection of the user’s firewall and Internet router.

Residential proxy networks are sold as a way for customers to anonymize and localize their Web traffic to a specific region, and the biggest of these services allow customers to route their traffic through devices in virtually any country or city around the globe.

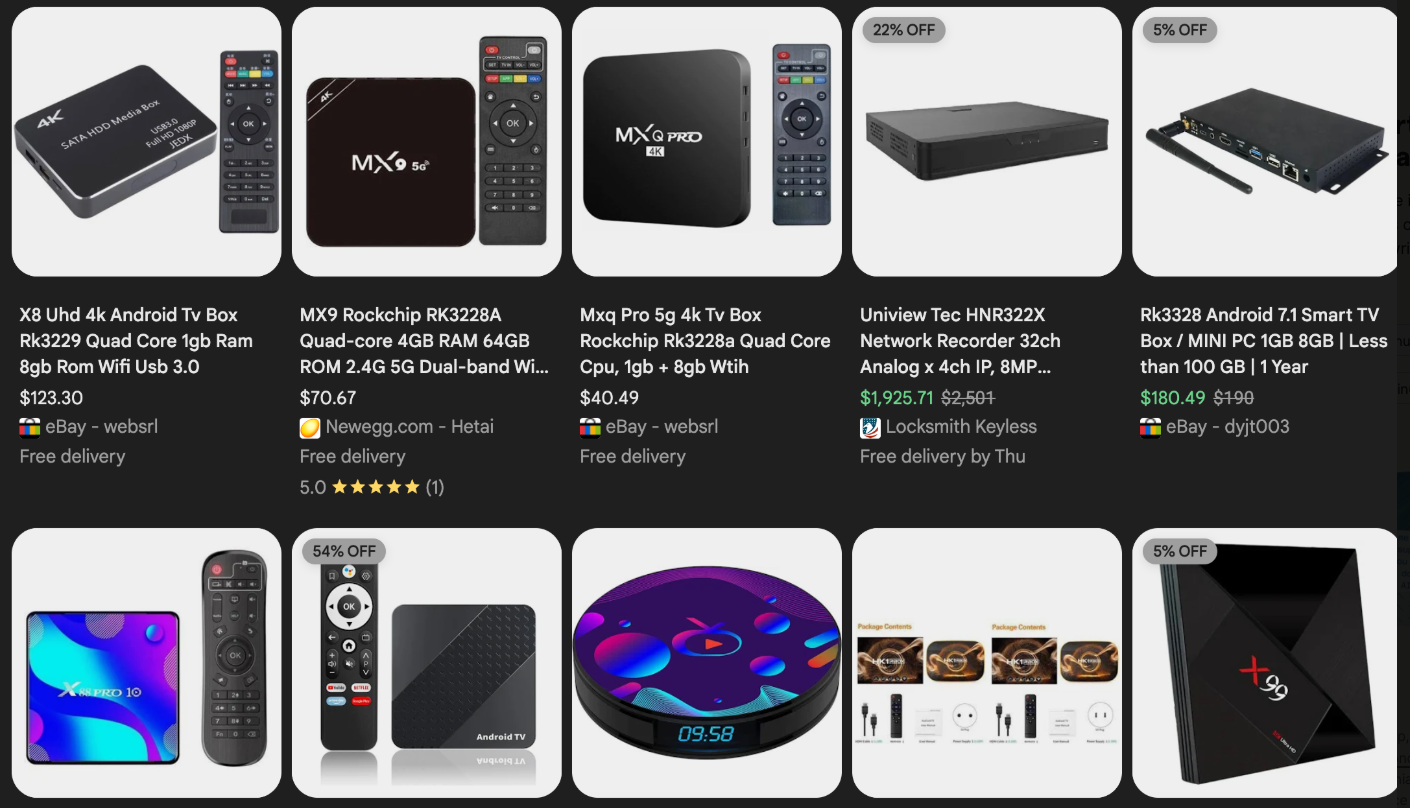

The malware that turns an end-user’s Internet connection into a proxy node is often bundled with dodgy mobile apps and games. These residential proxy programs also are commonly installed via unofficial Android TV boxes sold by third-party merchants on popular e-commerce sites like Amazon, BestBuy, Newegg, and Walmart.

These TV boxes range in price from $40 to $400, are marketed under a dizzying range of no-name brands and model numbers, and frequently are advertised as a way to stream certain types of subscription video content for free. But there’s a hidden cost to this transaction: As we’ll explore in a moment, these TV boxes make up a considerable chunk of the estimated two million systems currently infected with Kimwolf.

Some of the unsanctioned Android TV boxes that come with residential proxy malware pre-installed. Image: Synthient.

Kimwolf also is quite good at infecting a range of Internet-connected digital photo frames that likewise are abundant at major e-commerce websites. In November 2025, researchers from Quokka published a report (PDF) detailing serious security issues in Android-based digital picture frames running the Uhale app — including Amazon’s bestselling digital frame as of March 2025.

There are two major security problems with these photo frames and unofficial Android TV boxes. The first is that a considerable percentage of them come with malware pre-installed, or else require the user to download an unofficial Android App Store and malware in order to use the device for its stated purpose (video content piracy). The most typical of these uninvited guests are small programs that turn the device into a residential proxy node that is resold to others.

The second big security nightmare with these photo frames and unsanctioned Android TV boxes is that they rely on a handful of Internet-connected microcomputer boards that have no discernible security or authentication requirements built-in. In other words, if you are on the same network as one or more of these devices, you can likely compromise them simultaneously by issuing a single command across the network.

The combination of these two security realities came to the fore in October 2025, when an undergraduate computer science student at the Rochester Institute of Technology began closely tracking Kimwolf’s growth, and interacting directly with its apparent creators on a daily basis.

Benjamin Brundage is the 22-year-old founder of the security firm Synthient, a startup that helps companies detect proxy networks and learn how those networks are being abused. Conducting much of his research into Kimwolf while studying for final exams, Brundage told KrebsOnSecurity in late October 2025 he suspected Kimwolf was a new Android-based variant of Aisuru, a botnet that was incorrectly blamed for a number of record-smashing DDoS attacks last fall.

Brundage says Kimwolf grew rapidly by abusing a glaring vulnerability in many of the world’s largest residential proxy services. The crux of the weakness, he explained, was that these proxy services weren’t doing enough to prevent their customers from forwarding requests to internal servers of the individual proxy endpoints.

Most proxy services take basic steps to prevent their paying customers from “going upstream” into the local network of proxy endpoints, by explicitly denying requests for local addresses specified in RFC-1918, including the well-known Network Address Translation (NAT) ranges 10.0.0.0/8, 192.168.0.0/16, and 172.16.0.0/12. These ranges allow multiple devices in a private network to access the Internet using a single public IP address, and if you run any kind of home or office network, your internal address space operates within one or more of these NAT ranges.

However, Brundage discovered that the people operating Kimwolf had figured out how to talk directly to devices on the internal networks of millions of residential proxy endpoints, simply by changing their Domain Name System (DNS) settings to match those in the RFC-1918 address ranges.

“It is possible to circumvent existing domain restrictions by using DNS records that point to 192.168.0.1 or 0.0.0.0,” Brundage wrote in a first-of-its-kind security advisory sent to nearly a dozen residential proxy providers in mid-December 2025. “This grants an attacker the ability to send carefully crafted requests to the current device or a device on the local network. This is actively being exploited, with attackers leveraging this functionality to drop malware.”

As with the digital photo frames mentioned above, many of these residential proxy services run solely on mobile devices that are running some game, VPN or other app with a hidden component that turns the user’s mobile phone into a residential proxy — often without any meaningful consent.

In a report published today, Synthient said key actors involved in Kimwolf were observed monetizing the botnet through app installs, selling residential proxy bandwidth, and selling its DDoS functionality.

“Synthient expects to observe a growing interest among threat actors in gaining unrestricted access to proxy networks to infect devices, obtain network access, or access sensitive information,” the report observed. “Kimwolf highlights the risks posed by unsecured proxy networks and their viability as an attack vector.”

After purchasing a number of unofficial Android TV box models that were most heavily represented in the Kimwolf botnet, Brundage further discovered the proxy service vulnerability was only part of the reason for Kimwolf’s rapid rise: He also found virtually all of the devices he tested were shipped from the factory with a powerful feature called Android Debug Bridge (ADB) mode enabled by default.

Many of the unofficial Android TV boxes infected by Kimwolf include the ominous disclaimer: “Made in China. Overseas use only.” Image: Synthient.

ADB is a diagnostic tool intended for use solely during the manufacturing and testing processes, because it allows the devices to be remotely configured and even updated with new (and potentially malicious) firmware. However, shipping these devices with ADB turned on creates a security nightmare because in this state they constantly listen for and accept unauthenticated connection requests.

For example, opening a command prompt and typing “adb connect” along with a vulnerable device’s (local) IP address followed immediately by “:5555” will very quickly offer unrestricted “super user” administrative access.

Brundage said by early December, he’d identified a one-to-one overlap between new Kimwolf infections and proxy IP addresses offered for rent by China-based IPIDEA, currently the world’s largest residential proxy network by all accounts.

“Kimwolf has almost doubled in size this past week, just by exploiting IPIDEA’s proxy pool,” Brundage told KrebsOnSecurity in early December as he was preparing to notify IPIDEA and 10 other proxy providers about his research.

Brundage said Synthient first confirmed on December 1, 2025 that the Kimwolf botnet operators were tunneling back through IPIDEA’s proxy network and into the local networks of systems running IPIDEA’s proxy software. The attackers dropped the malware payload by directing infected systems to visit a specific Internet address and to call out the pass phrase “krebsfiveheadindustries” in order to unlock the malicious download.

On December 30, Synthient said it was tracking roughly 2 million IPIDEA addresses exploited by Kimwolf in the previous week. Brundage said he has witnessed Kimwolf rebuilding itself after one recent takedown effort targeting its control servers — from almost nothing to two million infected systems just by tunneling through proxy endpoints on IPIDEA for a couple of days.

Brundage said IPIDEA has a seemingly inexhaustible supply of new proxies, advertising access to more than 100 million residential proxy endpoints around the globe in the past week alone. Analyzing the exposed devices that were part of IPIDEA’s proxy pool, Synthient said it found more than two-thirds were Android devices that could be compromised with no authentication needed.

After charting a tight overlap in Kimwolf-infected IP addresses and those sold by IPIDEA, Brundage was eager to make his findings public: The vulnerability had clearly been exploited for several months, although it appeared that only a handful of cybercrime actors were aware of the capability. But he also knew that going public without giving vulnerable proxy providers an opportunity to understand and patch it would only lead to more mass abuse of these services by additional cybercriminal groups.

On December 17, Brundage sent a security notification to all 11 of the apparently affected proxy providers, hoping to give each at least a few weeks to acknowledge and address the core problems identified in his report before he went public. Many proxy providers who received the notification were resellers of IPIDEA that white-labeled the company’s service.

KrebsOnSecurity first sought comment from IPIDEA in October 2025, in reporting on a story about how the proxy network appeared to have benefitted from the rise of the Aisuru botnet, whose administrators appeared to shift from using the botnet primarily for DDoS attacks to simply installing IPIDEA’s proxy program, among others.

On December 25, KrebsOnSecurity received an email from an IPIDEA employee identified only as “Oliver,” who said allegations that IPIDEA had benefitted from Aisuru’s rise were baseless.

“After comprehensively verifying IP traceability records and supplier cooperation agreements, we found no association between any of our IP resources and the Aisuru botnet, nor have we received any notifications from authoritative institutions regarding our IPs being involved in malicious activities,” Oliver wrote. “In addition, for external cooperation, we implement a three-level review mechanism for suppliers, covering qualification verification, resource legality authentication and continuous dynamic monitoring, to ensure no compliance risks throughout the entire cooperation process.”

“IPIDEA firmly opposes all forms of unfair competition and malicious smearing in the industry, always participates in market competition with compliant operation and honest cooperation, and also calls on the entire industry to jointly abandon irregular and unethical behaviors and build a clean and fair market ecosystem,” Oliver continued.

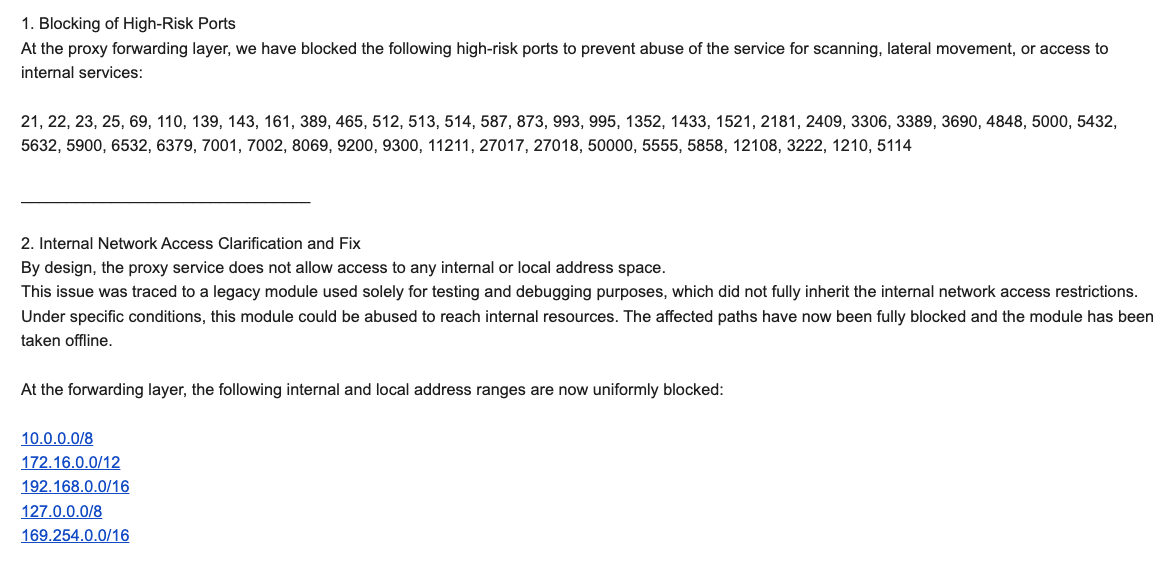

Meanwhile, the same day that Oliver’s email arrived, Brundage shared a response he’d just received from IPIDEA’s security officer, who identified himself only by the first name Byron. The security officer said IPIDEA had made a number of important security changes to its residential proxy service to address the vulnerability identified in Brundage’s report.

“By design, the proxy service does not allow access to any internal or local address space,” Byron explained. “This issue was traced to a legacy module used solely for testing and debugging purposes, which did not fully inherit the internal network access restrictions. Under specific conditions, this module could be abused to reach internal resources. The affected paths have now been fully blocked and the module has been taken offline.”

Byron told Brundage IPIDEA also instituted multiple mitigations for blocking DNS resolution to internal (NAT) IP ranges, and that it was now blocking proxy endpoints from forwarding traffic on “high-risk” ports “to prevent abuse of the service for scanning, lateral movement, or access to internal services.”

An excerpt from an email sent by IPIDEA’s security officer in response to Brundage’s vulnerability notification. Click to enlarge.

Brundage said IPIDEA appears to have successfully patched the vulnerabilities he identified. He also noted he never observed the Kimwolf actors targeting proxy services other than IPIDEA, which has not responded to requests for comment.

Riley Kilmer is founder of Spur.us, a technology firm that helps companies identify and filter out proxy traffic. Kilmer said Spur has tested Brundage’s findings and confirmed that IPIDEA and all of its affiliate resellers indeed allowed full and unfiltered access to the local LAN.

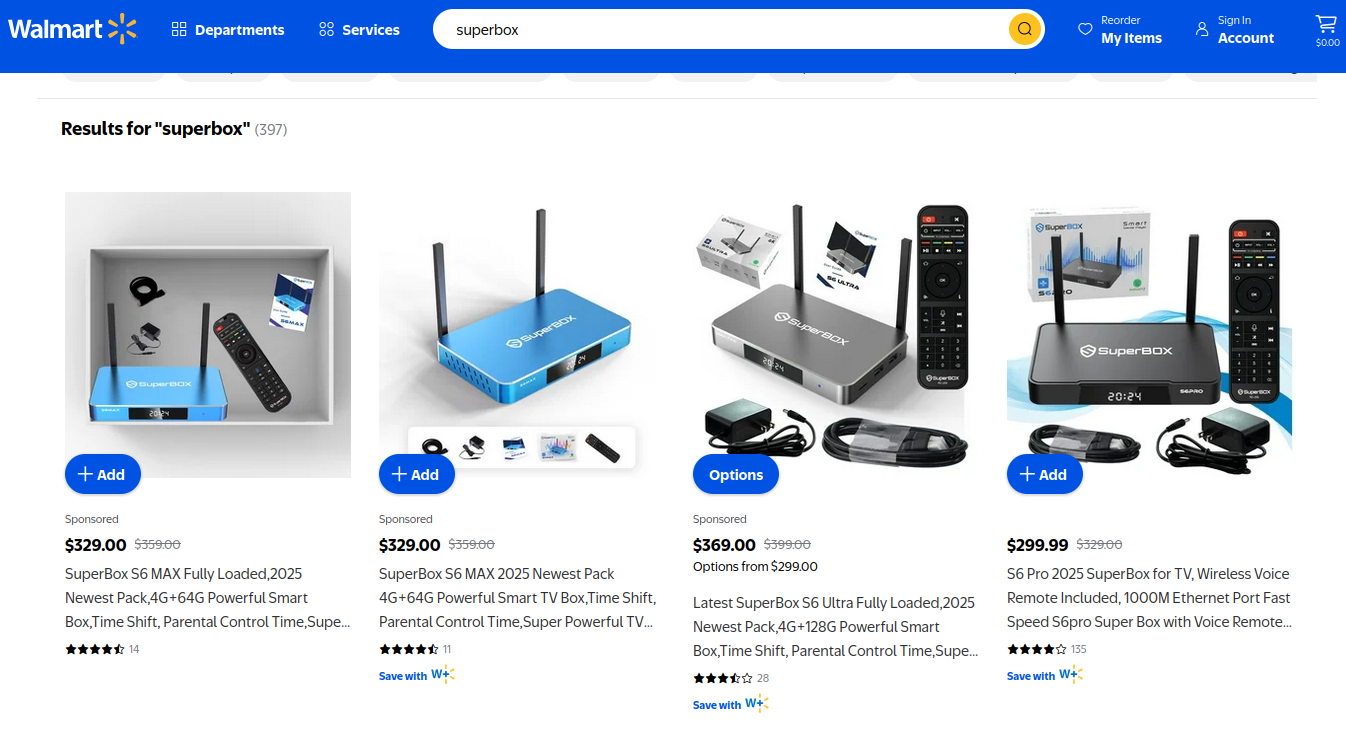

Kilmer said one model of unsanctioned Android TV boxes that is especially popular — the Superbox, which we profiled in November’s Is Your Android TV Streaming Box Part of a Botnet? — leaves Android Debug Mode running on localhost:5555.

“And since Superbox turns the IP into an IPIDEA proxy, a bad actor just has to use the proxy to localhost on that port and install whatever bad SDKs [software development kits] they want,” Kilmer told KrebsOnSecurity.

Superbox media streaming boxes for sale on Walmart.com.

Both Brundage and Kilmer say IPIDEA appears to be the second or third reincarnation of a residential proxy network formerly known as 911S5 Proxy, a service that operated between 2014 and 2022 and was wildly popular on cybercrime forums. 911S5 Proxy imploded a week after KrebsOnSecurity published a deep dive on the service’s sketchy origins and leadership in China.

In that 2022 profile, we cited work by researchers at the University of Sherbrooke in Canada who were studying the threat 911S5 could pose to internal corporate networks. The researchers noted that “the infection of a node enables the 911S5 user to access shared resources on the network such as local intranet portals or other services.”

“It also enables the end user to probe the LAN network of the infected node,” the researchers explained. “Using the internal router, it would be possible to poison the DNS cache of the LAN router of the infected node, enabling further attacks.”

911S5 initially responded to our reporting in 2022 by claiming it was conducting a top-down security review of the service. But the proxy service abruptly closed up shop just one week later, saying a malicious hacker had destroyed all of the company’s customer and payment records. In July 2024, The U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned the alleged creators of 911S5, and the U.S. Department of Justice arrested the Chinese national named in my 2022 profile of the proxy service.

Kilmer said IPIDEA also operates a sister service called 922 Proxy, which the company has pitched from Day One as a seamless alternative to 911S5 Proxy.

“You cannot tell me they don’t want the 911 customers by calling it that,” Kilmer said.

Among the recipients of Synthient’s notification was the proxy giant Oxylabs. Brundage shared an email he received from Oxylabs’ security team on December 31, which acknowledged Oxylabs had started rolling out security modifications to address the vulnerabilities described in Synthient’s report.

Reached for comment, Oxylabs confirmed they “have implemented changes that now eliminate the ability to bypass the blocklist and forward requests to private network addresses using a controlled domain.” But it said there is no evidence that Kimwolf or other other attackers exploited its network.

“In parallel, we reviewed the domains identified in the reported exploitation activity and did not observe traffic associated with them,” the Oxylabs statement continued. “Based on this review, there is no indication that our residential network was impacted by these activities.”

Consider the following scenario, in which the mere act of allowing someone to use your Wi-Fi network could lead to a Kimwolf botnet infection. In this example, a friend or family member comes to stay with you for a few days, and you grant them access to your Wi-Fi without knowing that their mobile phone is infected with an app that turns the device into a residential proxy node. At that point, your home’s public IP address will show up for rent at the website of some residential proxy provider.

Miscreants like those behind Kimwolf then use residential proxy services online to access that proxy node on your IP, tunnel back through it and into your local area network (LAN), and automatically scan the internal network for devices with Android Debug Bridge mode turned on.

By the time your guest has packed up their things, said their goodbyes and disconnected from your Wi-Fi, you now have two devices on your local network — a digital photo frame and an unsanctioned Android TV box — that are infected with Kimwolf. You may have never intended for these devices to be exposed to the larger Internet, and yet there you are.

Here’s another possible nightmare scenario: Attackers use their access to proxy networks to modify your Internet router’s settings so that it relies on malicious DNS servers controlled by the attackers — allowing them to control where your Web browser goes when it requests a website. Think that’s far-fetched? Recall the DNSChanger malware from 2012 that infected more than a half-million routers with search-hijacking malware, and ultimately spawned an entire security industry working group focused on containing and eradicating it.

Much of what is published so far on Kimwolf has come from the Chinese security firm XLab, which was the first to chronicle the rise of the Aisuru botnet in late 2024. In its latest blog post, XLab said it began tracking Kimwolf on October 24, when the botnet’s control servers were swamping Cloudflare’s DNS servers with lookups for the distinctive domain 14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132[.]su.

This domain and others connected to early Kimwolf variants spent several weeks topping Cloudflare’s chart of the Internet’s most sought-after domains, edging out Google.com and Apple.com of their rightful spots in the top 5 most-requested domains. That’s because during that time Kimwolf was asking its millions of bots to check in frequently using Cloudflare’s DNS servers.

The Chinese security firm XLab found the Kimwolf botnet had enslaved between 1.8 and 2 million devices, with heavy concentrations in Brazil, India, The United States of America and Argentina. Image: blog.xLab.qianxin.com

It is clear from reading the XLab report that KrebsOnSecurity (and security experts) probably erred in misattributing some of Kimwolf’s early activities to the Aisuru botnet, which appears to be operated by a different group entirely. IPDEA may have been truthful when it said it had no affiliation with the Aisuru botnet, but Brundage’s data left no doubt that its proxy service clearly was being massively abused by Aisuru’s Android variant, Kimwolf.

XLab said Kimwolf has infected at least 1.8 million devices, and has shown it is able to rebuild itself quickly from scratch.

“Analysis indicates that Kimwolf’s primary infection targets are TV boxes deployed in residential network environments,” XLab researchers wrote. “Since residential networks usually adopt dynamic IP allocation mechanisms, the public IPs of devices change over time, so the true scale of infected devices cannot be accurately measured solely by the quantity of IPs. In other words, the cumulative observation of 2.7 million IP addresses does not equate to 2.7 million infected devices.”

XLab said measuring Kimwolf’s size also is difficult because infected devices are distributed across multiple global time zones. “Affected by time zone differences and usage habits (e.g., turning off devices at night, not using TV boxes during holidays, etc.), these devices are not online simultaneously, further increasing the difficulty of comprehensive observation through a single time window,” the blog post observed.

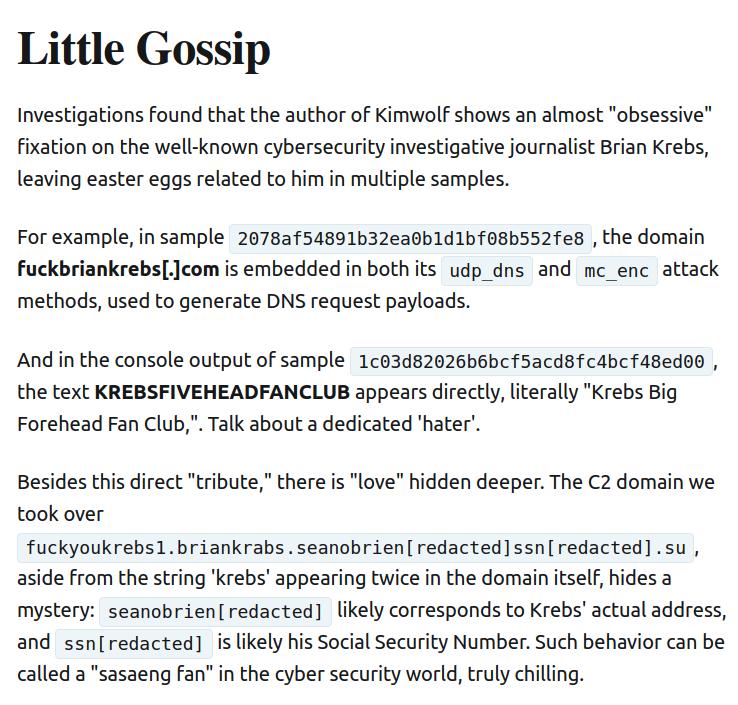

XLab noted that the Kimwolf author shows an almost ‘obsessive’ fixation” on Yours Truly, apparently leaving “easter eggs” related to my name in multiple places through the botnet’s code and communications:

Image: XLAB.

One frustrating aspect of threats like Kimwolf is that in most cases it is not easy for the average user to determine if there are any devices on their internal network which may be vulnerable to threats like Kimwolf and/or already infected with residential proxy malware.

Let’s assume that through years of security training or some dark magic you can successfully identify that residential proxy activity on your internal network was linked to a specific mobile device inside your house: From there, you’d still need to isolate and remove the app or unwanted component that is turning the device into a residential proxy.

Also, the tooling and knowledge needed to achieve this kind of visibility just isn’t there from an average consumer standpoint. The work that it takes to configure your network so you can see and interpret logs of all traffic coming in and out is largely beyond the skillset of most Internet users (and, I’d wager, many security experts). But it’s a topic worth exploring in an upcoming story.

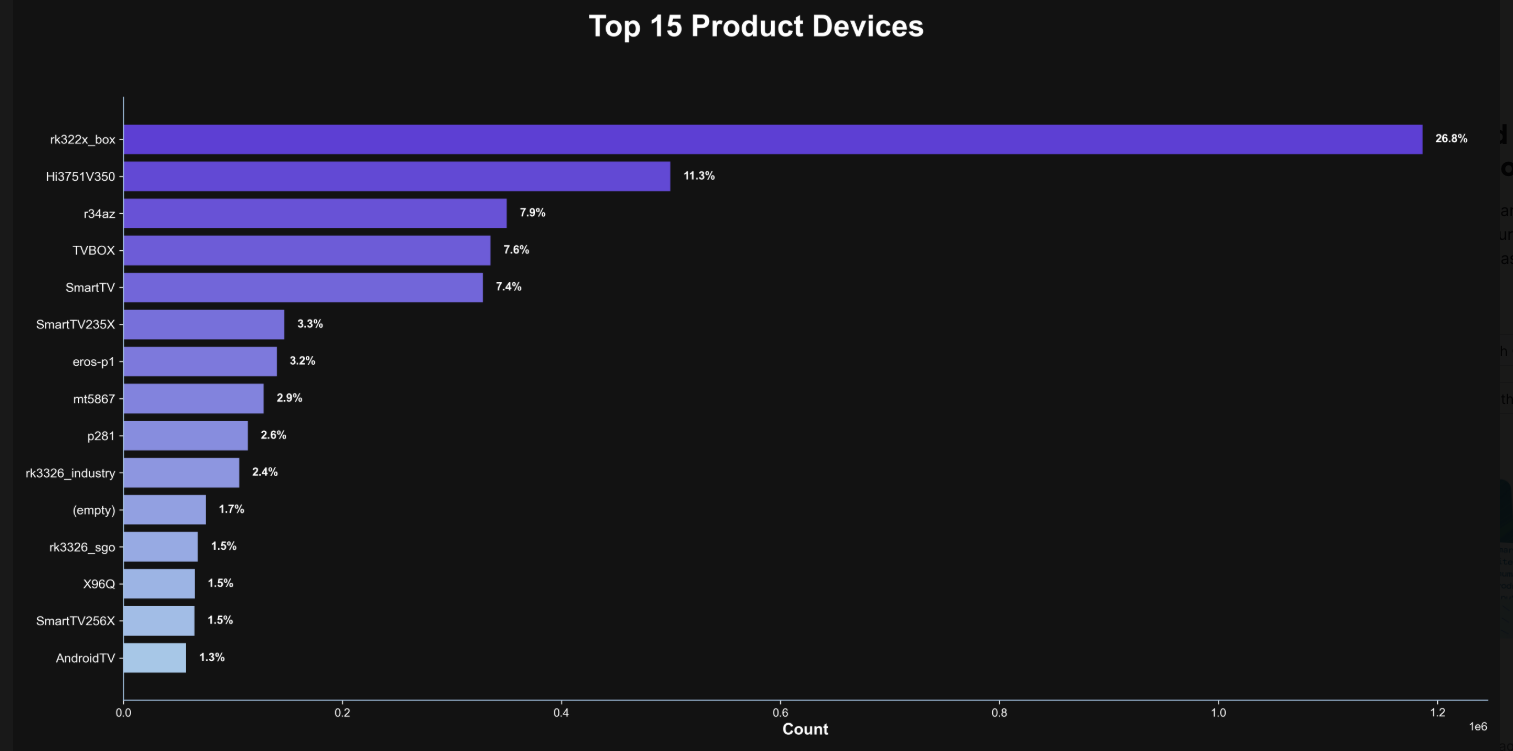

Happily, Synthient has erected a page on its website that will state whether a visitor’s public Internet address was seen among those of Kimwolf-infected systems. Brundage also has compiled a list of the unofficial Android TV boxes that are most highly represented in the Kimwolf botnet.

If you own a TV box that matches one of these model names and/or numbers, please just rip it out of your network. If you encounter one of these devices on the network of a family member or friend, send them a link to this story and explain that it’s not worth the potential hassle and harm created by keeping them plugged in.

The top 15 product devices represented in the Kimwolf botnet, according to Synthient.

Chad Seaman is a principal security researcher with Akamai Technologies. Seaman said he wants more consumers to be wary of these pseudo Android TV boxes to the point where they avoid them altogether.

“I want the consumer to be paranoid of these crappy devices and of these residential proxy schemes,” he said. “We need to highlight why they’re dangerous to everyone and to the individual. The whole security model where people think their LAN (Local Internal Network) is safe, that there aren’t any bad guys on the LAN so it can’t be that dangerous is just really outdated now.”

“The idea that an app can enable this type of abuse on my network and other networks, that should really give you pause,” about which devices to allow onto your local network, Seaman said. “And it’s not just Android devices here. Some of these proxy services have SDKs for Mac and Windows, and the iPhone. It could be running something that inadvertently cracks open your network and lets countless random people inside.”

In July 2025, Google filed a “John Doe” lawsuit (PDF) against 25 unidentified defendants collectively dubbed the “BadBox 2.0 Enterprise,” which Google described as a botnet of over ten million unsanctioned Android streaming devices engaged in advertising fraud. Google said the BADBOX 2.0 botnet, in addition to compromising multiple types of devices prior to purchase, also can infect devices by requiring the download of malicious apps from unofficial marketplaces.

Google’s lawsuit came on the heels of a June 2025 advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which warned that cyber criminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by either configuring the products with malware prior to the user’s purchase, or infecting the device as it downloads required applications that contain backdoors — usually during the set-up process.

The FBI said BADBOX 2.0 was discovered after the original BADBOX campaign was disrupted in 2024. The original BADBOX was identified in 2023, and primarily consisted of Android operating system devices that were compromised with backdoor malware prior to purchase.

Lindsay Kaye is vice president of threat intelligence at HUMAN Security, a company that worked closely on the BADBOX investigations. Kaye said the BADBOX botnets and the residential proxy networks that rode on top of compromised devices were detected because they enabled a ridiculous amount of advertising fraud, as well as ticket scalping, retail fraud, account takeovers and content scraping.

Kaye said consumers should stick to known brands when it comes to purchasing things that require a wired or wireless connection.

“If people are asking what they can do to avoid being victimized by proxies, it’s safest to stick with name brands,” Kaye said. “Anything promising something for free or low-cost, or giving you something for nothing just isn’t worth it. And be careful about what apps you allow on your phone.”

Many wireless routers these days make it relatively easy to deploy a “Guest” wireless network on-the-fly. Doing so allows your guests to browse the Internet just fine but it blocks their device from being able to talk to other devices on the local network — such as shared folders, printers and drives. If someone — a friend, family member, or contractor — requests access to your network, give them the guest Wi-Fi network credentials if you have that option.

There is a small but vocal pro-piracy camp that is almost condescendingly dismissive of the security threats posed by these unsanctioned Android TV boxes. These tech purists positively chafe at the idea of people wholesale discarding one of these TV boxes. A common refrain from this camp is that Internet-connected devices are not inherently bad or good, and that even factory-infected boxes can be flashed with new firmware or custom ROMs that contain no known dodgy software.

However, it’s important to point out that the majority of people buying these devices are not security or hardware experts; the devices are sought out because they dangle something of value for “free.” Most buyers have no idea of the bargain they’re making when plugging one of these dodgy TV boxes into their network.

It is somewhat remarkable that we haven’t yet seen the entertainment industry applying more visible pressure on the major e-commerce vendors to stop peddling this insecure and actively malicious hardware that is largely made and marketed for video piracy. These TV boxes are a public nuisance for bundling malicious software while having no apparent security or authentication built-in, and these two qualities make them an attractive nuisance for cybercriminals.

Stay tuned for Part II in this series, which will poke through clues left behind by the people who appear to have built Kimwolf and benefited from it the most.

Because Android uses an open source operating system, it usually gets a bad rap for being vulnerable to data loss and compromised apps as a result of malware, insecure app coding, unprotected cloud storage, outdated software, sideloading from untrusted sources, and even specific website vulnerabilities. Suffice it to say that any of these risks can be destructive and costly.

While Google addresses specific vulnerabilities, cyberthreats continue to evolve as criminals become more scheming or desperate. For these reasons, it is still best to exercise caution to protect the data on your device. In this article, we will share vital tips on how you can secure your device.

Determining if you’re vulnerable isn’t always easy. There are, however, some measures you can take to protect your device.

Your first line of defense against Android vulnerability threats is maintaining current software. Android security patches fix security weaknesses that cybercriminals actively take advantage of to access your personal data, install malware, or take control of your device. When you delay updates, you leave known security gaps open for attackers to exploit.

To enable automatic updates, navigate to Settings > System > System update > Advanced settings, then toggle on “Automatic system updates.” For Google Pixel devices, security updates typically arrive monthly, while other manufacturers may have varying schedules.

On top of this, set your Google Play Store to auto-update apps by opening the Play Store, tapping your profile picture, going to Settings > Network preferences > Auto-update apps, and selecting “Over any network” if you have unlimited data or “Over Wi-Fi only” to preserve your data plan.

One of the most effective Android phone security best practices is restricting app installations to the Google Play Store. Sideloading apps from unknown sources significantly increases your risk of installing malware, spyware, or apps with hidden malicious functionality.

Before installing any app, examine the permissions it requests. Apps asking for excessive permissions should raise your suspicions. Navigate to Settings > Apps > Special app access > Install unknown apps and ensure all toggles are disabled.

In addition, choose apps with consistent positive ratings and active developer responses to user concerns. Google’s Play Console policies provide guidelines for safe app development, but your vigilance remains essential.

Google Play Protect scans over 125 billion apps daily for malware and policy violations. While not perfect, this automated screening catches the majority of malicious apps before they reach your device, and even detects them after installation. In contrast, apps outside this ecosystem lack this protection layer.

Activate Play Protect by opening Google Play Store, tapping your profile picture, selecting “Play Protect,” and ensuring both “Scan apps with Play Protect” and “Improve harmful app detection” are enabled. This service runs automatic security scans and can remove or disable harmful apps even after you’ve installed them.

For comprehensive, real-time protection against phishing sites, malware downloads, and suspicious web content, enable safe browsing Android features in Chrome. Open Chrome, tap the three dots menu, go to Settings > Privacy and security > Safe Browsing, and select “Enhanced protection.” This setting checks URLs against Google’s constantly updated database of dangerous sites.

Modern Android devices offer multiple authentication methods, and using them strategically provides layered security for your most sensitive information. Set up a strong screen lock by going to Settings > Security > Screen lock and choosing either a complex PIN with at least 6 digits, a pattern with at least 6 points, or a password that combines letters, numbers, and symbols.

Enable biometric authentication, whether fingerprint and/or facial recognition, as an additional layer, but always maintain a strong backup PIN or password since biometrics can be circumvented.

For critical applications containing sensitive data such as banking apps, password managers, email clients, and social media, enable two-factor authentication (2FA) where possible for extra security.

Android’s built-in backup and encryption features provide essential protection against data loss from device theft, hardware failure, malware attacks, or accidental deletion, forming a crucial part of your Android incident response strategy.

Enable automatic backups of your app data, call history, and device settings by navigating to Settings > System > Backup, then toggle on “Back up to Google Drive.” You can set the frequency to daily. For photos and videos, enable Google Photos backup with high-quality or original quality settings based on your storage plan.

Device encryption can be activated through Settings > Security > Encryption & credentials > Encrypt phone. Modern Android devices (Android 6.0+) typically have encryption enabled by default, but you will need to verify this setting. Google’s Android backup service documentation provides detailed information on what data is protected and how to manage your backup settings effectively.

Your Google account serves as the master key to most Android functionality, so having an account recovery system can be invaluable to restore access to your device when local authentication methods fail. To ensure your recovery information is current, visit Security settings on your account profile, add a secondary email address that you can access independently, but avoid using another Gmail account as your backup. Include a mobile phone number for SMS verification, and consider adding multiple phone numbers if you frequently travel or change devices.

Google also provides one-time-use back-up codes that can restore account access when other methods fail. Download these codes and store them securely offline. Consider using a password manager like Google’s built-in option or a reputable third-party solution. Never store recovery codes in easily accessible digital formats like unencrypted text files or photos on the same device.

Google’s Find My Device service provides powerful remote management capabilities that can prevent permanent data loss during Android vulnerability situations or lockout scenarios. This service allows you to locate, lock, or completely erase your device remotely.

To enable this feature, navigate to Find My Device through Settings > Security > Find My Device. Ensure that your location services remain active for this feature to function properly.

Take note that when you decide to remotely erase your data from your device, this feature completely wipes all local data but preserves the information you backed up to Google’s cloud services. Only use this option when you’re certain your back-up systems are current.

Android offers multiple backup solutions that transform potential data disasters into minor inconveniences. To store your photos, videos, SMS messages, and call logs, you can go to Settings > System > Backup and choose the frequency that matches your usage patterns, daily backups for heavy users, weekly for lighter usage.

For sensitive information that you would like to access even when offline, you might want to consider periodic local backups by connecting your device to a computer monthly and copying important files manually. Test your systems regularly by attempting to restore a small amount of data to ensure your backups work when needed and identify any gaps in your protection strategy.

A mobile security incident can escalate from a nuisance to real damage in minutes, especially if an attacker can access your accounts, intercept messages, or install persistent apps. Speed matters when you respond, especially when prioritizing the high-impact steps that will stop the bleeding, regain control, and protect your data before you move on to cleanup and recovery. The actions below follow that order, so you can respond calmly and effectively even under stress.

When evaluating mobile security solutions for your Android device, focus on apps that offer comprehensive protection across multiple threat vectors. The most effective solutions combine several key capabilities into a single, user-friendly platform that doesn’t slow down your device or drain your battery.

Your Android device holds your most precious digital memories, important work files, and personal information, making it a prime target for cybercriminals who continue to exploit new vulnerabilities. While threats like remote factory resets and malicious web attacks can disrupt your daily digital routine, you do have the power to protect yourself against them by keeping your OS and security patches current, enabling Google Play Protect and built-in safe browsing features, maintaining regular backups of your essential data, and considering a comprehensive mobile security solution that provides real-time protection. For additional steps to safeguard your Android mobile life, visit McAfee’s security best practices.

The post Guard Your Android Phones Against Loss of Data and Infected Apps appeared first on McAfee Blog.

The practice of locking our possessions is relevant in every aspect of our modern lives. We physically lock our houses, cars, bikes, hotel rooms, computers, and even our luggage when we go to the airport. There are lockers at gyms, schools, amusement parks, and sometimes even at the workplace.

Digitally, we lock our phones with passcodes and protect them from malware with a security solution. Why, then, don’t we lock the individual apps that house some of our most personal and sensitive data?

From photos to emails to credit card numbers, our mobile apps hold invaluable data that is often left unprotected, especially given that some of the most commonly used apps on the Android platform such as Facebook, LinkedIn and Gmail don’t necessarily require a log in each time they’re launched.

Without an added layer of security, those apps are leaving room for nosy family members, jealous significant others, prankster friends, and worst of all thieves to hack into your social media or email accounts at the drop of a hat. In this article, we will discuss what an app lock is, everyday scenarios you may need it, and how to set it up on your smartphone.

Your mobile phone is more than just a gadget. It’s your wallet, camera, diary, and connection to the world. You likely keep photos, messages, social media, payment apps, and even confidential work files on it. To protect these bits of personal information, we use PINs, patterns, or biometrics to lock our devices, but once the phone is open, every app is fair game.

I f someone were able to go beyond your phone’s lock screen and gain access to the information in your phone, how much of your life could they see? A friend could scroll through your photos. Your child could open your shopping app and make purchases. Or a thief could get into your banking and social media accounts in seconds.

One way to avoid this from happening is by applying an app lock, a digital padlock that adds an authentication step such as a password, pattern, or biometric before an application can be launched.

In your home, a locked front door keeps strangers out. But what happens if you unwittingly leave the front door unlocked and someone walks in? Without interior locks, your bedroom, office, and safe are now accessible to anyone.

This same concept applies to your device with unprotected apps. Once unlocked, apps like Gmail, Facebook, or mobile banking don’t always require you to log in every time. It’s convenient, until it’s not.

An app lock serves as an indoor lock, protecting your sensitive data even after an unauthorized person has accessed it, and maintaining privacy boundaries.

When you or another person attempts to open an app on your device, the system first triggers an authentication screen. After verifying your PIN, fingerprint, or face, the app will open, ensuring that your personal information stays off-limits to people who do not know your authentication step. In Android, app locks work seamlessly in the background without slowing performance.

This layered defense mirrors the cybersecurity approach used on enterprise systems, but scaled down for consumers. Each layer handles different threats, so if one fails, the others still protect you:

Leaving apps unprotected can do more than just embarrass you. Here are some examples of how unprotected apps could lead to lasting harm:

Even just one unauthorized session could cascade into identity theft or financial fraud. That’s why security experts recommend app-level protection as part of a layered, reinforced mobile defense strategy.

While many Android phones include some app-locking capabilities, dedicated mobile security apps provide more robust options and better protection. Here’s how to set up app locks effectively:

Use a 6-digit or longer PIN, complex pattern, or biometric such as fingerprint or face unlock. Avoid using the same PIN as your main device.

Choose the priority mobile apps that you want to protect. Start with your most sensitive apps, such as:

Set timeouts based on app sensitivity:

Hide notification content for locked apps. This keeps private messages or bank alerts from showing up on your lock screen.

Most Android manufacturers now offer convenient, built-in app locking features. However, they are limited, often lacking biometric integration, cloud backup, or smart settings.

Dedicated solutions go further, providing:

With an app lock, your mischievous friends will never be able to post embarrassing status updates on your Facebook profile, and your jealous partner won’t be able to snoop through your photos or emails. For parents, you can keep your kids locked out of the apps that would allow them to access inappropriate content without having to watch their every move.

Most importantly, app locks protect you from thieves and strangers in case of a stolen or lost device.

Your phone carries more than just apps. It holds the details of your daily life. From private conversations and family photos to financial information and work data, much of what matters most to you lives behind those app icons. While a device lock is an important first step, it isn’t always enough on its own.

App locks give you greater control over your privacy by protecting individual apps, even when your phone is already unlocked. They help prevent accidental access, discourage snooping, and reduce the risk of serious harm if your device is lost or stolen. Most importantly, they allow you to use and share your phone, without worrying about who might see what they shouldn’t.

By adding app-level protection to your mobile security routine, you’re taking a simple but meaningful step toward safeguarding your personal information.

The post App Locks Can Improve the Security of Your Mobile Phones appeared first on McAfee Blog.

It’s no longer possible to deny that your life in the physical world and your digital life are one and the same. Coming to terms with this reality will help you make better decisions in many aspects of your life.

The same identity you use at work, at home, and with friends also exists in apps, inboxes, accounts, devices, and databases, whether you actively post online or prefer to stay quiet. Every purchase, login, location ping, and message leaves a trail. And that trail shapes what people, companies, and scammers can learn about you, how they can reach you, and what they might try to take.

That’s why digital security isn’t just an IT or a “tech person” problem. It’s a daily life skill. When you understand how your digital life works, what information you’re sharing, where it’s stored, and how it can be misused, you make better decisions. This guide is designed to help you build that awareness and translate it into practical habits: protecting your data, securing your accounts, and staying in control of your privacy in a world that’s always connected.

Being digitally secure doesn’t mean hiding from the internet or using complicated tools you don’t understand. It means having intentional control over your digital life to reduce risks while still being able to live, work, and communicate online safely. A digitally secure person focuses on four interconnected areas:

Your personal data is the foundation of your digital identity. Protecting it includes limiting how much data you share, understanding where it’s stored, and reducing how easily it can be collected, sold, or stolen. At its heart, personal information falls into two critical categories that require different levels of protection:

Account security ensures that only you can access them. Strong, unique passwords, multi-factor authentication, and secure recovery options prevent criminals from hijacking your email, banking, cloud storage, social media, and other online accounts, often the gateway to everything else in your digital life.

Privacy control means setting boundaries and deciding who can see what about you, and under what circumstances. This includes managing social media visibility, app permissions, browser tracking, and third-party access to your data.

Digital security is an ongoing effort as threats evolve, platforms change their policies, and new technologies introduce new risks. Staying digitally secure requires periodic check-ins, learning to recognize scams and manipulation, and adjusting your habits as the digital landscape changes.

Your personal information faces exposure risks through multiple channels during routine digital activities, often without your explicit knowledge.

Implementing comprehensive personal data protection requires a systematic approach that addresses the common exposure points. These practical steps provide layers of security that work together to minimize your exposure to identity theft and fraud.

Start by conducting a thorough audit of your online accounts and subscriptions to identify where you have unnecessarily shared more data than needed. Remove or minimize details that aren’t essential for the service to function. Moving forward, provide only the minimum required information to new accounts and avoid linking them across different platforms unless necessary.

Be particularly cautious with loyalty programs, surveys, and promotional offers that ask for extensive personal information, as they may share it with third parties. Read privacy policies carefully, focusing on sections that describe data sharing, retention periods, and your rights regarding your personal information.

If possible, consider using separate email addresses for different accounts to limit cross-platform tracking and reduce the impact if one account is compromised. Create dedicated email addresses for shopping, social media, newsletters, and important accounts like banking and healthcare.

Privacy protection requires regular attention to your account settings across all platforms and services you use. Social media platforms frequently update their privacy policies and settings, often defaulting to less private configurations that allow them to collect and share your data. For this reason, it is a good idea to review your privacy settings at least quarterly. Limit who can see your posts, contact information, and friend lists. Disable location tracking, facial recognition, and advertising customization features that rely on your personal data. Turn off automatic photo tagging and prevent search engines from indexing your profile.

On Google accounts, visit your Activity Controls and disable Web & App Activity, Location History, and YouTube History to stop this data from being saved. You can even opt out of ad personalization entirely if desired by adjusting Google Ad Settings. If you are more tech savvy, Google Takeout allows you to export and review what data Google has collected about you.

For Apple ID accounts, you can navigate to System Preferences on Mac or Settings on iOS devices to disable location-based Apple ads, limit app tracking, and review which apps have access to your contacts, photos, and other personal data.

Meanwhile, Amazon accounts store extensive purchase history, voice recordings from Alexa devices, and browsing behavior. Review your privacy settings to limit data sharing with third parties, delete voice recordings, and manage your advertising preferences.

Regularly audit the permissions you’ve granted to installed applications. Many apps request far more permissions to your location, contacts, camera, and microphone even though they don’t need them. Cancel these unnecessary permissions, and be particularly cautious about granting access to sensitive data.

Create passwords that actually protect you; they should be long and complex enough that even sophisticated attacks can’t easily break them. Combine uppercase letters, lowercase letters, numbers, and special characters to make it harder for attackers to crack.

Aside from passwords, enable multi-factor authentication (MFA) on your most critical accounts: banking and financial services, email, cloud storage, social media, work, and healthcare. Use authenticator apps such as Google Authenticator, Microsoft Authenticator, or Authy rather than SMS-based authentication when possible, as text messages can be intercepted through SIM swapping attacks. When setting up MFA, ensure you save backup codes in a secure location and register multiple devices when possible to keep you from being locked out of your accounts if your primary authentication device is lost, stolen, or damaged.

Alternatively, many services now offer passkeys which use cryptographic keys stored on your device, providing stronger security than passwords while being more convenient to use. Consider adopting passkeys for accounts that support them, particularly for your most sensitive accounts.

Device encryption protects your personal information if your smartphone, tablet, or laptop is lost, stolen, or accessed without authorization. Modern devices typically offer built-in encryption options that are easy to enable and don’t noticeably impact performance.

You can implement automatic backup systems such as secure cloud storage services, and ensure backup data is protected. iOS users can utilize encrypted iCloud backups, while Android users should enable Google backup with encryption. Regularly test your backup systems to ensure they’re working correctly and that you can successfully restore your data when needed.

Identify major data brokers that likely have your information and look for their privacy policy or opt-out procedures, which often involves submitting a request with your personal information and waiting for confirmation that your data has been removed.

In addition, review your subscriptions and memberships to identify services you no longer use. Request account deletion rather than simply closing accounts, as many companies retain data from closed accounts. When requesting deletion, ask specifically for all personal data to be removed from their systems, including backups and archives.

Keep records of your opt-out and deletion requests, and follow up if you don’t receive confirmation within the stated timeframe. In the United States, key data broker companies include Acxiom, LexisNexis, Experian, Equifax, TransUnion, Whitepages, Spokeo, BeenVerified, and PeopleFinder. Visit each company’s website.

Connect only to trusted, secure networks to reduce the risk of your data being intercepted by attackers lurking behind unsecured or fake Wi-Fi connections. Avoid logging into sensitive accounts on public networks in coffee shops, airports, or hotels, and use encrypted connections such as HTTPS or a virtual private network to hide your IP address and block third parties from monitoring your online activities.

Rather than using a free VPN service that often collects and sells your data to generate revenue, it is better to choose a premium, reputable VPN service that doesn’t log your browsing activities and offers servers in multiple locations.

Cyber threats evolve constantly, privacy policies change, and new services collect different types of personal information, making personal data protection an ongoing process rather than a one-time task. Here are measures to help regularly maintain your personal data protection:

By implementing these systematic approaches and maintaining regular attention to your privacy settings and data sharing practices, you significantly reduce your risk of identity theft and fraud while maintaining greater control over your digital presence and personal information.

You don’t need to dramatically overhaul your entire digital security in one day, but you can start making meaningful improvements right now. Taking action today, even small steps, builds the foundation for stronger personal data protection and peace of mind in your digital life. Choose one critical account, update its password, enable multi-factor authentication, and you’ll already be significantly more secure than you were this morning. Your future self will thank you for taking these proactive steps to protect what matters most to you.

Every step you take toward better privacy protection strengthens your overall digital security and reduces your risk of becoming a victim of scams, identity theft, or unwanted surveillance. You’ve already taken the first step by learning about digital security risks and solutions. Now it’s time to put that knowledge into action with practical steps that fit seamlessly into your digital routine.

The post What Does It Take To Be Digitally Secure? appeared first on McAfee Blog.

China-based purveyors of SMS phishing kits are enjoying remarkable success converting phished payment card data into mobile wallets from Apple and Google. Until recently, the so-called “Smishing Triad” mainly impersonated toll road operators and shipping companies. But experts say these groups are now directly targeting customers of international financial institutions, while dramatically expanding their cybercrime infrastructure and support staff.

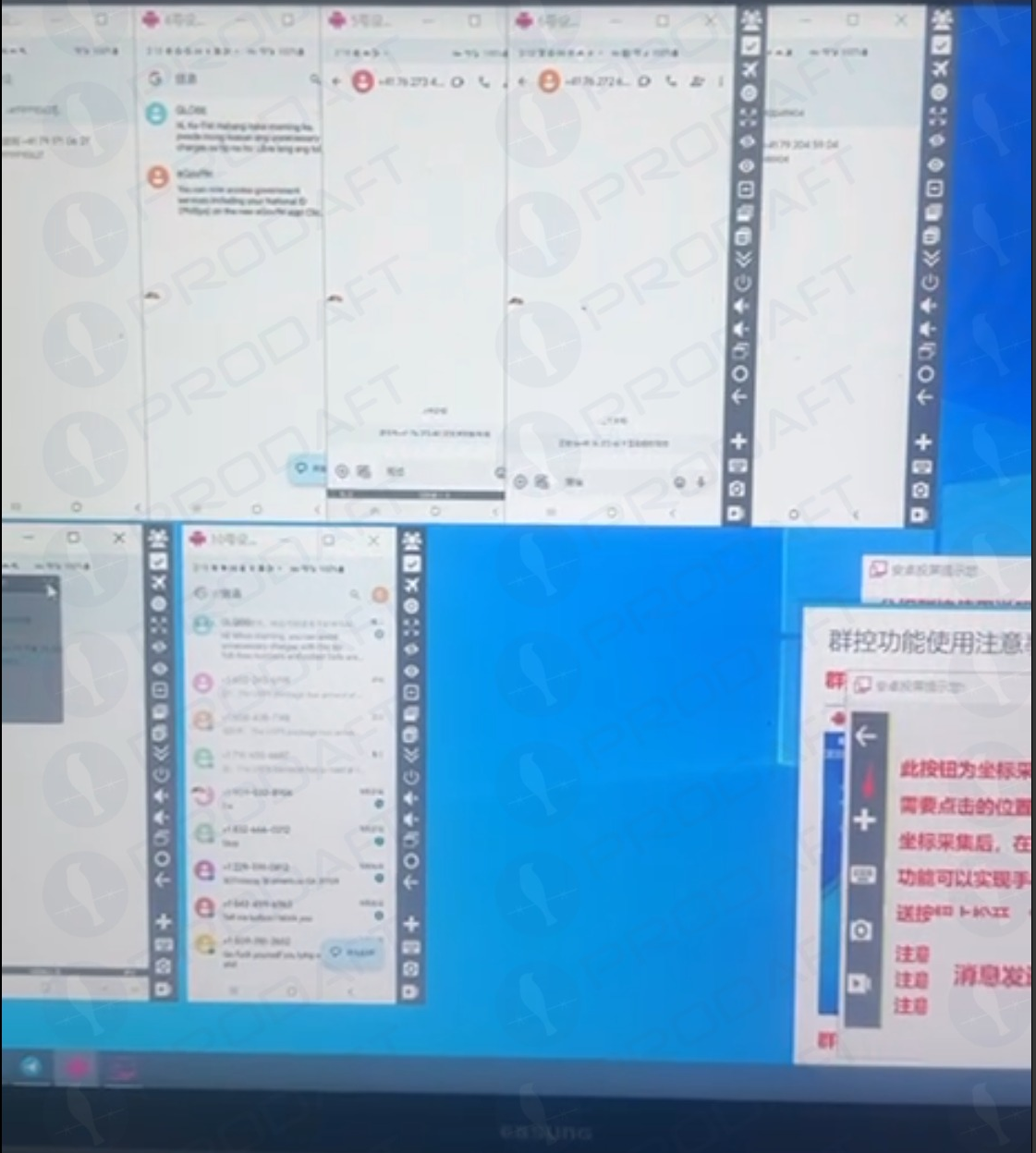

An image of an iPhone device farm shared on Telegram by one of the Smishing Triad members. Image: Prodaft.

If you own a mobile device, the chances are excellent that at some point in the past two years you’ve received at least one instant message that warns of a delinquent toll road fee, or a wayward package from the U.S. Postal Service (USPS). Those who click the promoted link are brought to a website that spoofs the USPS or a local toll road operator and asks for payment card information.

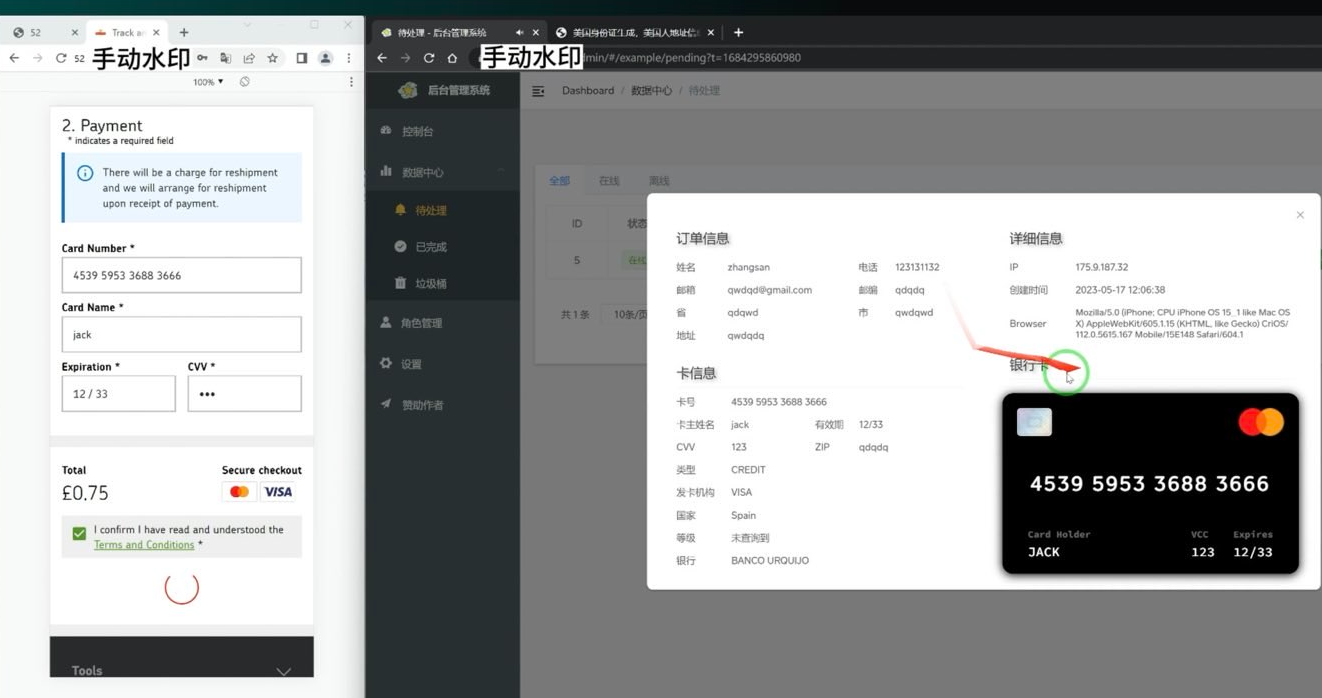

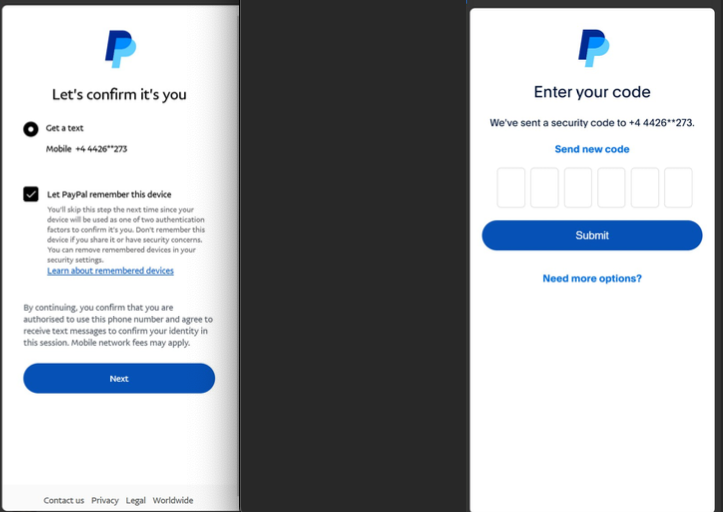

The site will then complain that the visitor’s bank needs to “verify” the transaction by sending a one-time code via SMS. In reality, the bank is sending that code to the mobile number on file for their customer because the fraudsters have just attempted to enroll that victim’s card details into a mobile wallet.

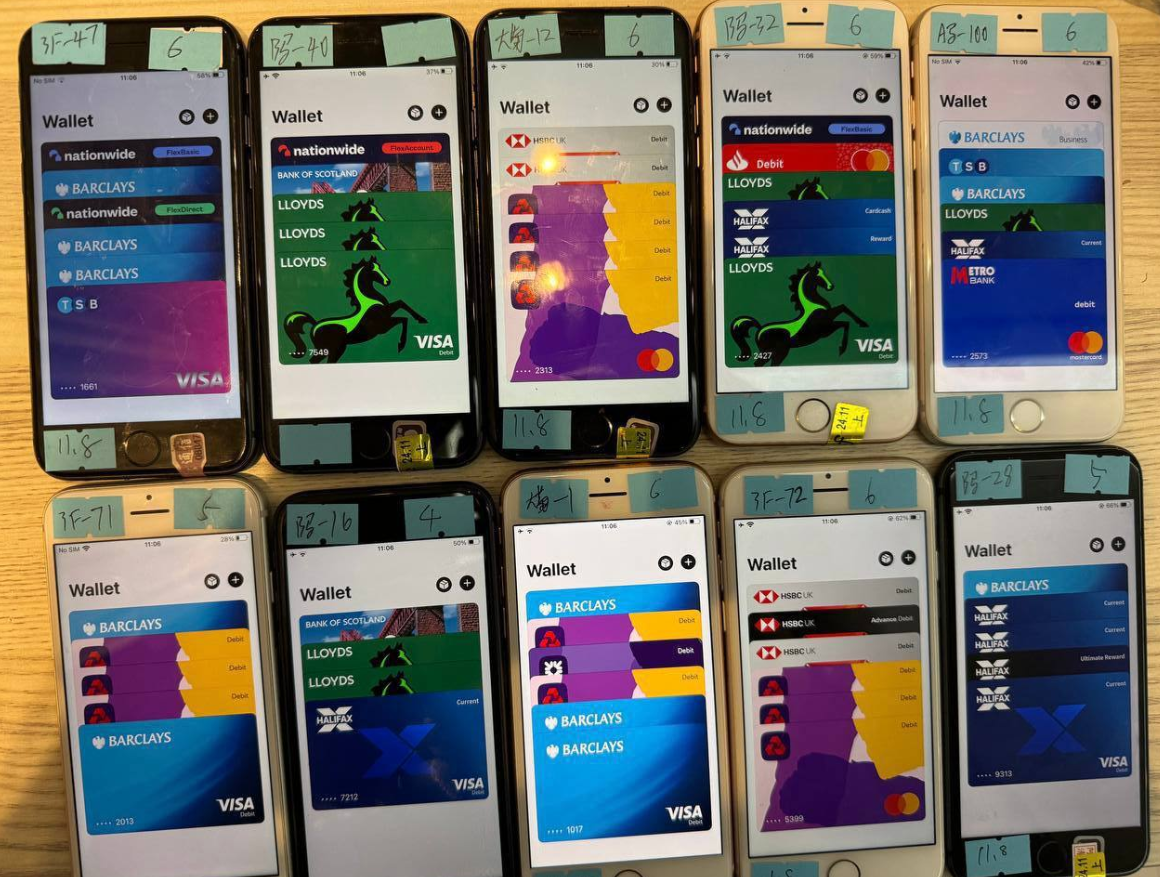

If the visitor supplies that one-time code, their payment card is then added to a new mobile wallet on an Apple or Google device that is physically controlled by the phishers. The phishing gangs typically load multiple stolen cards to digital wallets on a single Apple or Android device, and then sell those phones in bulk to scammers who use them for fraudulent e-commerce and tap-to-pay transactions.

A screenshot of the administrative panel for a smishing kit. On the left is the (test) data entered at the phishing site. On the right we can see the phishing kit has superimposed the supplied card number onto an image of a payment card. When the phishing kit scans that created card image into Apple or Google Pay, it triggers the victim’s bank to send a one-time code. Image: Ford Merrill.

The moniker “Smishing Triad” comes from Resecurity, which was among the first to report in August 2023 on the emergence of three distinct mobile phishing groups based in China that appeared to share some infrastructure and innovative phishing techniques. But it is a bit of a misnomer because the phishing lures blasted out by these groups are not SMS or text messages in the conventional sense.

Rather, they are sent via iMessage to Apple device users, and via RCS on Google Android devices. Thus, the missives bypass the mobile phone networks entirely and enjoy near 100 percent delivery rate (at least until Apple and Google suspend the spammy accounts).

In a report published on March 24, the Swiss threat intelligence firm Prodaft detailed the rapid pace of innovation coming from the Smishing Triad, which it characterizes as a loosely federated group of Chinese phishing-as-a-service operators with names like Darcula, Lighthouse, and the Xinxin Group.

Prodaft said they’re seeing a significant shift in the underground economy, particularly among Chinese-speaking threat actors who have historically operated in the shadows compared to their Russian-speaking counterparts.

“Chinese-speaking actors are introducing innovative and cost-effective systems, enabling them to target larger user bases with sophisticated services,” Prodaft wrote. “Their approach marks a new era in underground business practices, emphasizing scalability and efficiency in cybercriminal operations.”

A new report from researchers at the security firm SilentPush finds the Smishing Triad members have expanded into selling mobile phishing kits targeting customers of global financial institutions like CitiGroup, MasterCard, PayPal, Stripe, and Visa, as well as banks in Canada, Latin America, Australia and the broader Asia-Pacific region.

Phishing lures from the Smishing Triad spoofing PayPal. Image: SilentPush.

SilentPush found the Smishing Triad now spoofs recognizable brands in a variety of industry verticals across at least 121 countries and a vast number of industries, including the postal, logistics, telecommunications, transportation, finance, retail and public sectors.

According to SilentPush, the domains used by the Smishing Triad are rotated frequently, with approximately 25,000 phishing domains active during any 8-day period and a majority of them sitting at two Chinese hosting companies: Tencent (AS132203) and Alibaba (AS45102).

“With nearly two-thirds of all countries in the world targeted by [the] Smishing Triad, it’s safe to say they are essentially targeting every country with modern infrastructure outside of Iran, North Korea, and Russia,” SilentPush wrote. “Our team has observed some potential targeting in Russia (such as domains that mentioned their country codes), but nothing definitive enough to indicate Russia is a persistent target. Interestingly, even though these are Chinese threat actors, we have seen instances of targeting aimed at Macau and Hong Kong, both special administrative regions of China.”

SilentPush’s Zach Edwards said his team found a vulnerability that exposed data from one of the Smishing Triad’s phishing pages, which revealed the number of visits each site received each day across thousands of phishing domains that were active at the time. Based on that data, SilentPush estimates those phishing pages received well more than a million visits within a 20-day time span.

The report notes the Smishing Triad boasts it has “300+ front desk staff worldwide” involved in one of their more popular phishing kits — Lighthouse — staff that is mainly used to support various aspects of the group’s fraud and cash-out schemes.

The Smishing Triad members maintain their own Chinese-language sales channels on Telegram, which frequently offer videos and photos of their staff hard at work. Some of those images include massive walls of phones used to send phishing messages, with human operators seated directly in front of them ready to receive any time-sensitive one-time codes.

As noted in February’s story How Phished Data Turns Into Apple and Google Wallets, one of those cash-out schemes involves an Android app called Z-NFC, which can relay a valid NFC transaction from one of these compromised digital wallets to anywhere in the world. For a $500 month subscription, the customer can wave their phone at any payment terminal that accepts Apple or Google pay, and the app will relay an NFC transaction over the Internet from a stolen wallet on a phone in China.

Chinese nationals were recently busted trying to use these NFC apps to buy high-end electronics in Singapore. And in the United States, authorities in California and Tennessee arrested Chinese nationals accused of using NFC apps to fraudulently purchase gift cards from retailers.

The Prodaft researchers said they were able to find a previously undocumented backend management panel for Lucid, a smishing-as-a-service operation tied to the XinXin Group. The panel included victim figures that suggest the smishing campaigns maintain an average success rate of approximately five percent, with some domains receiving over 500 visits per week.

“In one observed instance, a single phishing website captured 30 credit card records from 550 victim interactions over a 7-day period,” Prodaft wrote.

Prodaft’s report details how the Smishing Triad has achieved such success in sending their spam messages. For example, one phishing vendor appears to send out messages using dozens of Android device emulators running in parallel on a single machine.

Phishers using multiple virtualized Android devices to orchestrate and distribute RCS-based scam campaigns. Image: Prodaft.

According to Prodaft, the threat actors first acquire phone numbers through various means including data breaches, open-source intelligence, or purchased lists from underground markets. They then exploit technical gaps in sender ID validation within both messaging platforms.

“For iMessage, this involves creating temporary Apple IDs with impersonated display names, while RCS exploitation leverages carrier implementation inconsistencies in sender verification,” Prodaft wrote. “Message delivery occurs through automated platforms using VoIP numbers or compromised credentials, often deployed in precisely timed multi-wave campaigns to maximize effectiveness.

In addition, the phishing links embedded in these messages use time-limited single-use URLs that expire or redirect based on device fingerprinting to evade security analysis, they found.

“The economics strongly favor the attackers, as neither RCS nor iMessage messages incur per-message costs like traditional SMS, enabling high-volume campaigns at minimal operational expense,” Prodaft continued. “The overlap in templates, target pools, and tactics among these platforms underscores a unified threat landscape, with Chinese-speaking actors driving innovation in the underground economy. Their ability to scale operations globally and evasion techniques pose significant challenges to cybersecurity defenses.”

Ford Merrill works in security research at SecAlliance, a CSIS Security Group company. Merrill said he’s observed at least one video of a Windows binary that wraps a Chrome executable and can be used to load in target phone numbers and blast messages via RCS, iMessage, Amazon, Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp.

“The evidence we’ve observed suggests the ability for a single device to send approximately 100 messages per second,” Merrill said. “We also believe that there is capability to source country specific SIM cards in volume that allow them to register different online accounts that require validation with specific country codes, and even make those SIM cards available to the physical devices long-term so that services that rely on checks of the validity of the phone number or SIM card presence on a mobile network are thwarted.”

Experts say this fast-growing wave of card fraud persists because far too many financial institutions still default to sending one-time codes via SMS for validating card enrollment in mobile wallets from Apple or Google. KrebsOnSecurity interviewed multiple security executives at non-U.S. financial institutions who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the press. Those banks have since done away with SMS-based one-time codes and are now requiring customers to log in to the bank’s mobile app before they can link their card to a digital wallet.

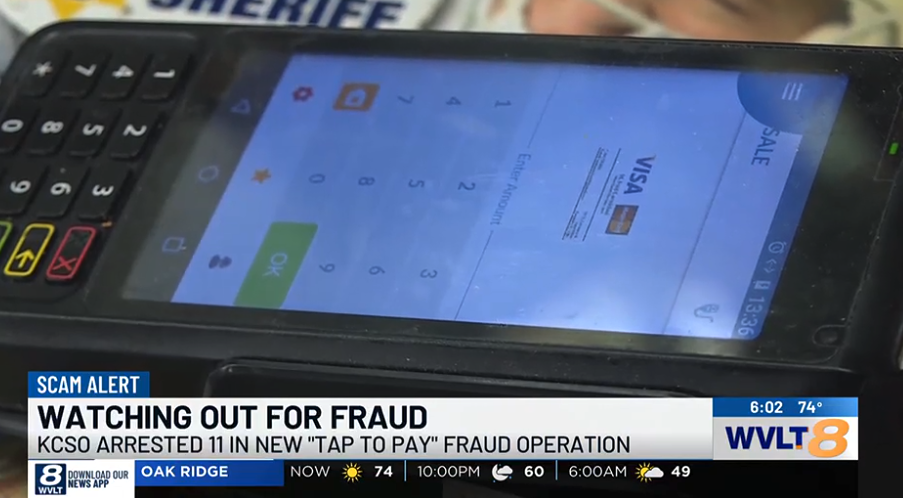

Authorities in at least two U.S. states last week independently announced arrests of Chinese nationals accused of perpetrating a novel form of tap-to-pay fraud using mobile devices. Details released by authorities so far indicate the mobile wallets being used by the scammers were created through online phishing scams, and that the accused were relying on a custom Android app to relay tap-to-pay transactions from mobile devices located in China.

Image: WLVT-8.

Authorities in Knoxville, Tennessee last week said they arrested 11 Chinese nationals accused of buying tens of thousands of dollars worth of gift cards at local retailers with mobile wallets created through online phishing scams. The Knox County Sheriff’s office said the arrests are considered the first in the nation for a new type of tap-to-pay fraud.

Responding to questions about what makes this scheme so remarkable, Knox County said that while it appears the fraudsters are simply buying gift cards, in fact they are using multiple transactions to purchase various gift cards and are plying their scam from state to state.

“These offenders have been traveling nationwide, using stolen credit card information to purchase gift cards and launder funds,” Knox County Chief Deputy Bernie Lyon wrote. “During Monday’s operation, we recovered gift cards valued at over $23,000, all bought with unsuspecting victims’ information.”

Asked for specifics about the mobile devices seized from the suspects, Lyon said “tap-to-pay fraud involves a group utilizing Android phones to conduct Apple Pay transactions utilizing stolen or compromised credit/debit card information,” [emphasis added].

Lyon declined to offer additional specifics about the mechanics of the scam, citing an ongoing investigation.

Ford Merrill works in security research at SecAlliance, a CSIS Security Group company. Merrill said there aren’t many valid use cases for Android phones to transmit Apple Pay transactions. That is, he said, unless they are running a custom Android app that KrebsOnSecurity wrote about last month as part of a deep dive into the operations of China-based phishing cartels that are breathing new life into the payment card fraud industry (a.k.a. “carding”).

How are these China-based phishing groups obtaining stolen payment card data and then loading it onto Google and Apple phones? It all starts with phishing.

If you own a mobile phone, the chances are excellent that at some point in the past two years it has received at least one phishing message that spoofs the U.S. Postal Service to supposedly collect some outstanding delivery fee, or an SMS that pretends to be a local toll road operator warning of a delinquent toll fee.

These messages are being sent through sophisticated phishing kits sold by several cybercriminals based in mainland China. And they are not traditional SMS phishing or “smishing” messages, as they bypass the mobile networks entirely. Rather, the missives are sent through the Apple iMessage service and through RCS, the functionally equivalent technology on Google phones.

People who enter their payment card data at one of these sites will be told their financial institution needs to verify the small transaction by sending a one-time passcode to the customer’s mobile device. In reality, that code will be sent by the victim’s financial institution in response to a request by the fraudsters to link the phished card data to a mobile wallet.

If the victim then provides that one-time code, the phishers will link the card data to a new mobile wallet from Apple or Google, loading the wallet onto a mobile phone that the scammers control. These phones are then loaded with multiple stolen wallets (often between 5-10 per device) and sold in bulk to scammers on Telegram.

An image from the Telegram channel for a popular Chinese smishing kit vendor shows 10 mobile phones for sale, each loaded with 5-7 digital wallets from different financial institutions.

Merrill found that at least one of the Chinese phishing groups sells an Android app called “Z-NFC” that can relay a valid NFC transaction to anywhere in the world. The user simply waves their phone at a local payment terminal that accepts Apple or Google pay, and the app relays an NFC transaction over the Internet from a phone in China.

“I would be shocked if this wasn’t the NFC relay app,” Merrill said, concerning the arrested suspects in Tennessee.

Merrill said the Z-NFC software can work from anywhere in the world, and that one phishing gang offers the software for $500 a month.

“It can relay both NFC enabled tap-to-pay as well as any digital wallet,” Merrill said. “They even have 24-hour support.”

On March 16, the ABC affiliate in Sacramento (ABC10), Calif. aired a segment about two Chinese nationals who were arrested after using an app to run stolen credit cards at a local Target store. The news story quoted investigators saying the men were trying to buy gift cards using a mobile app that cycled through more than 80 stolen payment cards.

ABC10 reported that while most of those transactions were declined, the suspects still made off with $1,400 worth of gift cards. After their arrests, both men reportedly admitted that they were being paid $250 a day to conduct the fraudulent transactions.

Merrill said it’s not unusual for fraud groups to advertise this kind of work on social media networks, including TikTok.

A CBS News story on the Sacramento arrests said one of the suspects tried to use 42 separate bank cards, but that 32 were declined. Even so, the man still was reportedly able to spend $855 in the transactions.

Likewise, the suspect’s alleged accomplice tried 48 transactions on separate cards, finding success 11 times and spending $633, CBS reported.

“It’s interesting that so many of the cards were declined,” Merrill said. “One reason this might be is that banks are getting better at detecting this type of fraud. The other could be that the cards were already used and so they were already flagged for fraud even before these guys had a chance to use them. So there could be some element of just sending these guys out to stores to see if it works, and if not they’re on their own.”

Merrill’s investigation into the Telegram sales channels for these China-based phishing gangs shows their phishing sites are actively manned by fraudsters who sit in front of giant racks of Apple and Google phones that are used to send the spam and respond to replies in real time.

In other words, the phishing websites are powered by real human operators as long as new messages are being sent. Merrill said the criminals appear to send only a few dozen messages at a time, likely because completing the scam takes manual work by the human operators in China. After all, most one-time codes used for mobile wallet provisioning are generally only good for a few minutes before they expire.

For more on how these China-based mobile phishing groups operate, check out How Phished Data Turns Into Apple and Google Wallets.

The ashtray says: You’ve been phishing all night.

Not long ago, the ability to digitally track someone’s daily movements just by knowing their home address, employer, or place of worship was considered a dangerous power that should remain only within the purview of nation states. But a new lawsuit in a likely constitutional battle over a New Jersey privacy law shows that anyone can now access this capability, thanks to a proliferation of commercial services that hoover up the digital exhaust emitted by widely-used mobile apps and websites.

Image: Shutterstock, Arthimides.

Delaware-based Atlas Data Privacy Corp. helps its users remove their personal information from the clutches of consumer data brokers, and from people-search services online. Backed by millions of dollars in litigation financing, Atlas so far this year has sued 151 consumer data brokers on behalf of a class that includes more than 20,000 New Jersey law enforcement officers who are signed up for Atlas services.

Atlas alleges all of these data brokers have ignored repeated warnings that they are violating Daniel’s Law, a New Jersey statute allowing law enforcement, government personnel, judges and their families to have their information completely removed from commercial data brokers. Daniel’s Law was passed in 2020 after the death of 20-year-old Daniel Anderl, who was killed in a violent attack targeting a federal judge — his mother.

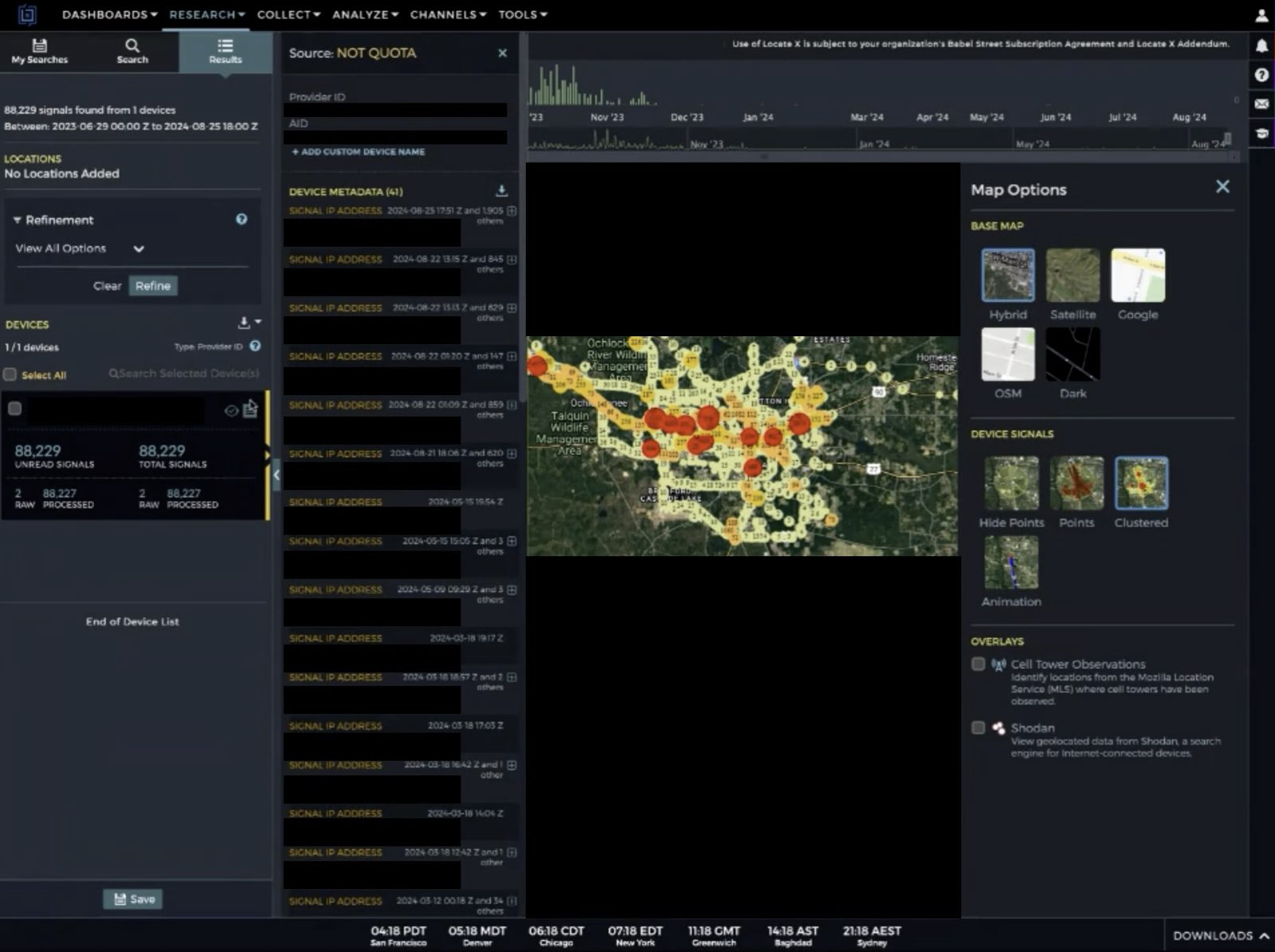

Last week, Atlas invoked Daniel’s Law in a lawsuit (PDF) against Babel Street, a little-known technology company incorporated in Reston, Va. Babel Street’s core product allows customers to draw a digital polygon around nearly any location on a map of the world, and view a slightly dated (by a few days) time-lapse history of the mobile devices seen coming in and out of the specified area.

Babel Street’s LocateX platform also allows customers to track individual mobile users by their Mobile Advertising ID or MAID, a unique, alphanumeric identifier built into all Google Android and Apple mobile devices.

Babel Street can offer this tracking capability by consuming location data and other identifying information that is collected by many websites and broadcast to dozens and sometimes hundreds of ad networks that may wish to bid on showing their ad to a particular user.

This image, taken from a video recording Atlas made of its private investigator using Babel Street to show all of the unique mobile IDs seen over time at a mosque in Dearborn, Michigan. Each red dot represents one mobile device.

In an interview, Atlas said a private investigator they hired was offered a free trial of Babel Street, which the investigator was able to use to determine the home address and daily movements of mobile devices belonging to multiple New Jersey police officers whose families have already faced significant harassment and death threats.

Atlas said the investigator encountered Babel Street while testing hundreds of data broker tools and services to see if personal information on its users was being sold. They soon discovered Babel Street also bundles people-search services with its platform, to make it easier for customers to zero in on a specific device.

The investigator contacted Babel Street about possibly buying home addresses in certain areas of New Jersey. After listening to a sales pitch for Babel Street and expressing interest, the investigator was told Babel Street only offers their service to the government or to “contractors of the government.”

“The investigator (truthfully) mentioned that he was contemplating some government contract work in the future and was told by the Babel Street salesperson that ‘that’s good enough’ and that ‘they don’t actually check,’” Atlas shared in an email with reporters.

KrebsOnSecurity was one of five media outlets invited to review screen recordings that Atlas made while its investigator used a two-week trial version of Babel Street’s LocateX service. References and links to reporting by other publications, including 404 Media, Haaretz, NOTUS, and The New York Times, will appear throughout this story.

Collectively, these stories expose how the broad availability of mobile advertising data has created a market in which virtually anyone can build a sophisticated spying apparatus capable of tracking the daily movements of hundreds of millions of people globally.

The findings outlined in Atlas’s lawsuit against Babel Street also illustrate how mobile location data is set to massively complicate several hot-button issues, from the tracking of suspected illegal immigrants or women seeking abortions, to harassing public servants who are already in the crosshairs over baseless conspiracy theories and increasingly hostile political rhetoric against government employees.

Atlas says the Babel Street trial period allowed its investigator to find information about visitors to high-risk targets such as mosques, synagogues, courtrooms and abortion clinics. In one video, an Atlas investigator showed how they isolated mobile devices seen in a New Jersey courtroom parking lot that was reserved for jurors, and then tracked one likely juror’s phone to their home address over several days.

While the Atlas investigator had access to its trial account at Babel Street, they were able to successfully track devices belonging to several plaintiffs named or referenced in the lawsuit. They did so by drawing a digital polygon around the home address or workplace of each person in Babel Street’s platform, which focused exclusively on the devices that passed through those addresses each day.

Each red dot in this Babel Street map represents a unique mobile device that has been seen since April 2022 at a Jewish synagogue in Los Angeles, Calif. Image: Atlas Data Privacy Corp.

One unique feature of Babel Street is the ability to toggle a “night” mode, which makes it relatively easy to determine within a few meters where a target typically lays their head each night (because their phone is usually not far away).

Atlas plaintiffs Scott and Justyna Maloney are both veteran officers with the Rahway, NJ police department who live together with their two young children. In April 2023, Scott and Justyna became the target of intense harassment and death threats after Officer Justyna responded to a routine call about a man filming people outside of the Motor Vehicle Commission in Rahway.

The man filming the Motor Vehicle Commission that day is a social media personality who often solicits police contact and then records himself arguing about constitutional rights with the responding officers.

Officer Justyna’s interaction with the man was entirely peaceful, and the episode appeared to end without incident. But after a selectively edited video of that encounter went viral, their home address and unpublished phone numbers were posted online. When their tormentors figured out that Scott was also a cop (a sergeant), the couple began receiving dozens of threatening text messages, including specific death threats.

According to the Atlas lawsuit, one of the messages to Mr. Maloney demanded money, and warned that his family would “pay in blood” if he didn’t comply. Sgt. Maloney said he then received a video in which a masked individual pointed a rifle at the camera and told him that his family was “going to get [their] heads cut off.”